I, for one, am tired of security lines and the lurking suspicion of all things beyond our borders. So it was a refreshing surprise to find an all-consuming case of xenophilia in Ben Katchor’s new graphic novel, The Cardboard Valise (Pantheon Books, March 2011). This is Katchor’s first book in a decade, and The Cardboard Valise carries his trademark blend of humor and irony, fluid pen strokes, and offbeat philosophical musings—this time on our motivations to journey abroad, and the often more difficult journey to find fulfillment at home.

I, for one, am tired of security lines and the lurking suspicion of all things beyond our borders. So it was a refreshing surprise to find an all-consuming case of xenophilia in Ben Katchor’s new graphic novel, The Cardboard Valise (Pantheon Books, March 2011). This is Katchor’s first book in a decade, and The Cardboard Valise carries his trademark blend of humor and irony, fluid pen strokes, and offbeat philosophical musings—this time on our motivations to journey abroad, and the often more difficult journey to find fulfillment at home.

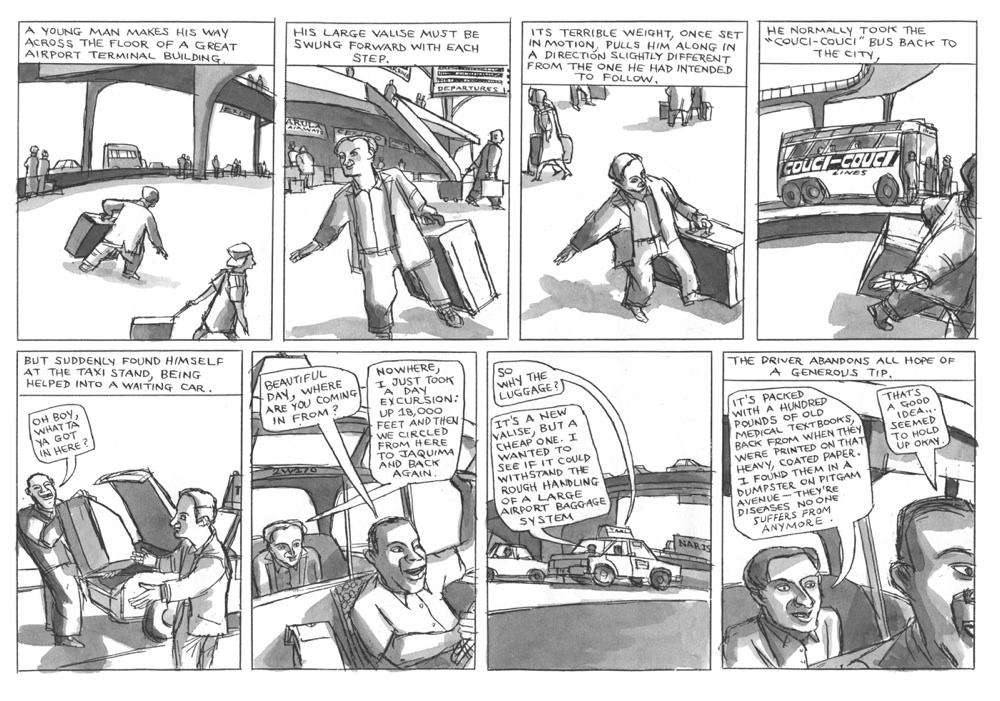

At the core of the graphic novel is Emile Delilah. Seduced by travel at an early age, he can neither hold a job nor have a normal relationship. Katchor portrays Delilah as a benign extremist, addicted to foreign lands and suffering from a condition he describes as “a morbid love for every nation but [one’s] own.” In fact, even when Delilah returns home to Fluxion City—apparently located seven miles southeast of Bayonne, New Jersey—he maintains the lifestyle of a tourist:

For some people it’s impossible to make the transition back to the workaday world. You’ve seen them—habitual vacationists. They’ve discovered that they feel most themselves in after-pool attire and see nothing wrong with sunbathing on a busy midtown street.

Over the course of the novel, Delilah’s xenophilia brings him on visits to curious destinations, including Tensint Island, home to world-famous restroom ruins. But it is the nation of Outer Canthus (that’s the anatomical term for the outside corner of one’s eye), a place of questionable charm, that is so irresistible that he finds himself returning over and over again.

Katchor has clearly relished the opportunity to invent a nation whose attributes seem vaguely familiar yet undeniably odd, part dusty Old World charm and part schoolboy fantasy. For example, it is a culture of great haters—verbally abusive inhabitants mutter phrases such as “That shovel nosed little martinet, I trespass on his mother’s vegetable garden” and the national hero is a man who invented the wireless transmission of odors. Visually, Katchor’s work has a distinctively sketchy, unrefined feel, with a gray wash in place of color, and an unerring sense of body language. His illustrations change continuously across the eight frames on each page, capturing buildings, streetscapes, and other curious settings both at close range and from afar. Meanwhile, the narrative—which is inserted across the top of each rectangular frame—and the dialogue are both hand-printed by Katchor in capital letters, making the experience feel both personal and informal.

Like the majority of the protagonists in Katchor’s previous graphic novels—such as Nathan Kishon in The Jew of New York, or Julius Knipl, the real estate photographer in the eponymous book—The Cardboard Valise‘s Delilah is a loner. He is also particularly susceptible to the nefarious schemers of the tourism industry. We glean the impression that he comes from a wealthy family and was raised by a succession of nannies, some ineffective, one cruel. When an ecological disaster obliterates one of his usual vacation destinations, and his parents instantly presume that he is dead, he muses, “My birth put a crimp in their social life, they were bored by my company as a teenager; they spent a fortune on baby sitters and psychiatrists… And so, they took the news of my premature death in their stride.” No wonder Delilah spends his life in a series of self-imposed exiles.

Whereas Delilah seeks solace in the landmarks of other civilizations, Katchor’s other protagonist is a self-styled prophet of the “supranationalist way”. Delilah’s neighbor in the dilapidated apartment building at 575 Kavanah Avenue, Elijah Salamis, has a band of devoted followers who eagerly report their findings of culturally stripped locales, from the building of vast, featureless housing developments to 24-hour food warehouses selling generic brands. He spends his time practicing Puncto, a universal language.

Preaching the erasure of national identity, Salamis’ vision of a world without borders is bland and predictable, or as Katchor says in a riff on processed turkey sandwich meat: “…it’s easier to live with; has no bones, skin or variations in color, texture or flavor – there are no unpleasant surprises”. Although Salamis has few endearing features—he takes the form of a myopic flâneur on the streets of Fluxion City—he appears to be genuine in his desire for a world without differences.

I struggled with the fact that these two rootless characters’ stories are so relentlessly parallel, seldom intersecting until the end of the book. Although this structure is clearly intentional, it leaves the reader a bit unmoored, searching for something more. Indeed, their only true interaction occurs when Salamis finds Delilah hovering outside his own memorial service. He succeeds in reuniting Delilah with his parents, while simultaneously exposing the conman on the pulpit as an exploitative fake: “I see an opportunity here. A chance to effect a secular resurrection, debunk another fraudulent religion and sabotage the memorial industry,” Salamis says to himself. This solves a significant problem for Delilah, yet it remains merely a chance meeting on the street, neither engaging the characters’ beliefs nor developing a relationship between them.

I struggled with the fact that these two rootless characters’ stories are so relentlessly parallel, seldom intersecting until the end of the book. Although this structure is clearly intentional, it leaves the reader a bit unmoored, searching for something more. Indeed, their only true interaction occurs when Salamis finds Delilah hovering outside his own memorial service. He succeeds in reuniting Delilah with his parents, while simultaneously exposing the conman on the pulpit as an exploitative fake: “I see an opportunity here. A chance to effect a secular resurrection, debunk another fraudulent religion and sabotage the memorial industry,” Salamis says to himself. This solves a significant problem for Delilah, yet it remains merely a chance meeting on the street, neither engaging the characters’ beliefs nor developing a relationship between them.

Perhaps more interesting is the tangent introduced by a third resident of the building, Boreal Rince, the supposed king of Outer Canthus, who “narrowly escaped death by taking an air-mail flight out of Gazogene City.” Although he plays a minor role in the novel—shortly after entering the story he is ousted from his apartment and surreptitiously makes his way back to Outer Canthus hidden in a large cardboard valise—his story serves as a reminder that travel is not always chosen, but often takes the form of an undesired displacement from home.

The jumble of imaginary languages, cuisines, and tourist attractions could potentially wear thin as a result of Katchor’s decision to cobble The Cardboard Valise strips into a full-length piece of work. However, that episodic jumpiness might be Katchor’s point—uncovering the often disjointed nature of travel. To quote the pop philosopher Alain de Botton in The Art of Travel,

Having made a journey to a place we may never revisit, we feel obliged to admire a sequence of things without any connection to one another besides a geographic one, a proper understanding of which would require qualities unlikely to be found in the same person. […] Travel twists our curiosity according to a superficial geographical logic, as superficial as if a university course were to prescribe books according to their size rather than subject matter.

The Cardboard Valise pokes fun at the tourism industry and those seeking an “authentic” experience in foreign lands, such as the explorer Rudolf Maennerchor, an anthropologist determined to discover the native culture of the Tensint Islands. More a bully than a scientific observer, however, it isn’t long before Maennerchor shoves a local boy up against a parked car and forces him to explain the meaning of an early morning gathering of islanders.

In the end, Katchor’s most subtle and moving point is one about self-awareness. In Hebrew, the word kavanah is used to express the idea of an introspective mindset, and Katchor has located the apartment building where the three characters live on, yes, Kavanah Avenue. Yet only Delilah seems to achieve some level of kavanah, eventually changing from a passive consumer of the travel experience to a more demanding one. Towards the end of the book he becomes abruptly disenchanted with his travels around Outer Canthus. Reading the guidebook on a walk, he notes, “I could’ve read that sentence in the comfort of my easy chair at home,” and in the gift shop he recoils from another traveler from Fluxion City, saying, “I didn’t come here to buy souvenirs.” He seems to realize that travel may have provided him with the illusion of greater happiness, but not the reality. Indeed, Katchor wants us to think about the dangers of delusion, something he illustrates with entertaining clarity throughout the novel.

Further Links & Resources:

- Visit Ben Katchor’s website—katchor.com—which links to his weekly comic strips, audio cartoons (!), and his fascinating blog, which ranges from Leo Tolstoy’s drawing-as-writing, and “The Golden Age of Urinal Design: c. 1885.”

- Read interviews with Katchor on the Daily Beast (3/4/11) and the Onion‘s AV Club (4/22/11).

- Interested in the interplay between words and pictures? Check out these other FWR features:

– Michael Rudin on “Writing the Next Great American Novel Video Game.”

– Lee Thomas’s review of We Are the Friction, a collection of illustrators and fiction writers in creative collaboration.

– Jesse Hassenger’s review of The Bottomless Bellybutton by Dash Shaw – 700 pages of evocative panels which tell the story of three grown siblings who reunite at their childhood home after hearing their elderly parents have decided to split up.