The question I often ask my creative writing class is, “What is the author accomplishing and how?” Maybe that’s two questions. Both are hard, especially with subjects such as motherhood that are often dismissed as pedantic or overlooked as not literary (enough).

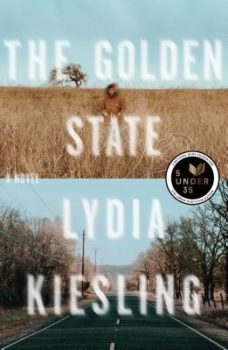

To get at the question of “how,” part of our discussion will invariably have to do with the formal aspects of the work, by which I mean sentence-level techniques that create meaning: rhythm, meter, and diction; tense shifts, tone, and point of view; white space, fragmentation, and so on. And though we don’t always give the same level of attention to syntax in fiction as we do when reading poetry, in The Golden State (MCD/Farrar, Straus and Giroux), Lydia Kiesling reminds us what we might gain if we do.

The Golden State is a novel about new motherhood, but it’s also about how bodies are reduced—or, retreat—to the essentials in the face of a world that has become overwhelming with parenting duties, immigration courts, the effects of globalism, and the strains these all have on a marriage. The story, set against the background of a road trip, is, as road trips often are, a quest for self. But our protagonist, Daphne, is on the other side of an identity crisis. She flees, with her toddler, to a family trailer in northern California, in search of answers about her marriage and stalled academic career. Both her job and motherhood have become wearisome, but the move only succeeds in relocating the tedious daily tasks of raising a toddler, further isolating her. Daphne’s husband, Engin, has been exiled to Turkey after giving up his green card. Like their lives, even their language becomes fragmentary and incomplete: “I gather Honey put her into pants and shirt cover her face and chubby wrists and arms and hands and ankles with sunscreen and it gets in her hair and we set out on the move.”

The Golden State is a novel about new motherhood, but it’s also about how bodies are reduced—or, retreat—to the essentials in the face of a world that has become overwhelming with parenting duties, immigration courts, the effects of globalism, and the strains these all have on a marriage. The story, set against the background of a road trip, is, as road trips often are, a quest for self. But our protagonist, Daphne, is on the other side of an identity crisis. She flees, with her toddler, to a family trailer in northern California, in search of answers about her marriage and stalled academic career. Both her job and motherhood have become wearisome, but the move only succeeds in relocating the tedious daily tasks of raising a toddler, further isolating her. Daphne’s husband, Engin, has been exiled to Turkey after giving up his green card. Like their lives, even their language becomes fragmentary and incomplete: “I gather Honey put her into pants and shirt cover her face and chubby wrists and arms and hands and ankles with sunscreen and it gets in her hair and we set out on the move.”

I was initially drawn to The Golden State because it was billed as a compelling portrait of modern parenting in a complicated world, but it’s Kiesling’s feast of form that makes a familiar topic fresh. For this linguistic patterning isn’t an isolated flourish. Regularly the sentences seem to be bent or stripped by the strain the narrator is experiencing and trying to convey in the telling. Early in the novel, she declares, “The problem with reproduction is that it is stressful, I mean becoming pregnant having the baby raising the baby, and all the measures I employ to deal with stress involve some measure of self-harm, and once you have a baby in or around your body that body is no longer just your own to harm.”

A well-intentioned reader might mark this early instance of Kiesling’s technique as a mistake missed by a copyeditor. But it isn’t. The patterning of run-on sentences and comma splices is intentionally exhausting and consistent throughout the novel. The often weaving of conjunctions (one paragraph alone contains more than thirty uses of “and”) demonstrates the joining of Daphne and Honey, mother and child, who depend on each other. They can’t be separated or they won’t survive, and neither can independent and dependent clauses. It’s a delightful exploitation of the form-follows-function structure. When you are “becoming pregnant having the baby raising the baby” it is a blur without the luxury of a comma to separate items in a series. How can a mother decide how to divide her body and her time and who has the sleep-deprived mind to draw boundaries? I’ve seen other writers capture the emotional or physical experience of parenting in astute and illuminating ways, but rarely one who has captured it at the structural level of the sentence in quite the same way.

Yet Kiesling is also attentive to the limits of these techniques and is adeptly aware of when to employ them. For example, when Daphne reaches her limits trying to communicate with her expatriated partner:

I pause for my daily feeling of annoyance at the difficulty of communicating overseas and while the difference between what is available now and what it used to be like for example when we lived in Nicosia it is somehow more annoying now, the Skype calls with an echo or video but no sound or sound but no video or work in one room but cut off when you wander into an electrical shadow or the Wi-Fi relies on ancient copper lines that don’t really work.

Here, she refuses the appositive phrase, she overuses “or” because choices don’t matter anymore. Contemporary life is simply grueling but there isn’t another option.

Similarly, repetition gestures toward the overwhelming nature of Daphne’s experience: “It’s obviously not Engin’s fault that he is having a beach day while I’m lugging a sweating toddler to a rural church service—it’s my fault for ensnaring him through marriage in the bureaucratic web of the evil empire, my fault for putting him in a position where his only chance to work was to go back to Turkey, my fault my fault. I know all these things but I am still full of fury.” Further, that “fault” is recurrent is obvious, but the “my” accusation is weighty in a culture of U.S. motherhood that expects so much and supports so little (I’m looking at you, lack of maternity leave).

The thing Daphne discovers, which my writing students have to learn too, is that it all exists together: the joy and angst, the simple sentence and compound-complex, the decision and the unknown, the devotion to your partner and the loathing of their breath. We want a simple, clear path and then we don’t want it when it arrives. “I sit her on the bed and then squat down before her and sort of scoop her onto my back and hold her there with one arm behind my back while the other arm fumbles for straps…” This sentence describing the mundane task of wrestling a toddler into a backpack carrier solo while they flail continues for ten more lines. It’s as arduous as the act. But it’s also entertaining and funny, as is the ridiculousness of the task.

That said, employing syntax in this manner risks a kind of fallacy of imitation. In the same way that crafting boring dialogue to illustrate how dull two characters might be doesn’t illuminate much more than that simple point, one of the risks of Kiesling’s choice to represent the strains of marriage and family and child rearing with the collapse of language itself is that making the point might end up overshadowing the nuance and depth of experience that it’s representing. Yet this author avoids that pitfall. Perhaps because of the complex nature of parenting itself. For once we are parents we can never fully escape ourselves. Carrying another human in your body teaches you that even language is not your own, let alone your body. That breakdown, that overlap, that absorption, that colonization—call it what you will—is exactly what Kiesling’s language represents. On day nine of the ten-day narrative, she writes:

I crawl to the foot of the bed and reach into the Pack ‘n Play and drag her up on the bed with me and lie back and she lies on me and puts her head under my chin and I am thinking Keep this moment, let’s keep this one and while I am trying to fossilize the moment or X-ray it or photocopy it or do something that will make it stay with me forever she is squirming thrashing rolling and she is off the bed, she is on the move and suddenly I have what I think may be my most important epiphany about motherhood which is that your child is not your property and motherhood is not a house you live in…

The Golden State is a compelling story and a brutally unromantic portrait of modern motherhood, but it’s also glowing at the sentence level in its intention. Daphne has to learn— and we get to watch the tussling—that motherhood, like formal elements of fiction, is something you must go through rather than around. There is the diaper and the bottle and first smile and the semi colon and the conjunction and em dash. Somehow, we survive and thrive or we endure and hope the words add up to something grander than they were solo. Lydia Kiesling is accomplishing a treatment of motherhood that lives in and through language, elevating a moment in a mother’s life from the banal to the beautiful.