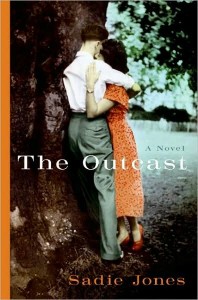

Sadie Jones’s exciting debut, The Outcast, is saturated in the same high color as the embracing couple on its cover. Like that couple, it manages to be simultaneously tender and urgent, claustrophobic and wistful. The Outcast tells the story of Lewis Aldridge, a tortured romantic figure in the Heathcliff tradition and of the repressive postwar English society that drives him to self-destruction.

Sadie Jones’s exciting debut, The Outcast, is saturated in the same high color as the embracing couple on its cover. Like that couple, it manages to be simultaneously tender and urgent, claustrophobic and wistful. The Outcast tells the story of Lewis Aldridge, a tortured romantic figure in the Heathcliff tradition and of the repressive postwar English society that drives him to self-destruction.

The novel opens in August, 1957 – the breathless summer heat appears again and again in this narrative, driving events to shocking climaxes, reflecting unrelenting hypocrisy everywhere – as Lewis, nineteen years old, returns from two years in prison for an unspecified crime. Then we’re taken back to the end of the Second World War, to the beginnings of Lewis’s troubles. His father, Gilbert, sees Lewis as an intrusion upon his relationship with his wife; his mother, Elizabeth, beautiful and free-spirited, refuses to play the games of her society. Gilbert is a postwar archetype: churchgoing, concerned (albeit somewhat guiltily) about appearances, troubled by war memories, yet unable to talk about them. He resents Elizabeth’s easy intimacy with Lewis, but instead of recognizing his jealousy for what it is, he tries to impose traditional roles upon his household. “You’ve been spoiling him,” he tells Elizabeth on his first night back home after the war. “You ought to have had a nanny.”

To improve his career prospects, Gilbert prostrates himself before his boss, Dicky Carmichael, who lords over the town (and beats his wife, and later his younger daughter, in secret). Alienated by a society at once primeval in its laws and precious in its manners, Elizabeth turns to drink, with disastrous consequences. Only one person understands the adolescent Lewis: Dicky’s daughter, Kit, softened by her father’s beatings and her mother’s cruel inattention. Can her empathy save Lewis from himself? Will he take her love seriously, even though she’s all of fifteen when he comes home from prison?

If the novel sounds a little melodramatic, or prone to cause-and-effect explanations, it’s because these are at once its strengths and limitations. Sadie Jones does not shy away from emotion, and it’s hard to summarize her novel without sounding like a Bollywood synopsis, but I say this as someone who loves these very aspects of Bollywood: its lack of restraint, its sweep and earnestness. In fact, Lewis reminds me less of Heathcliff than of Devdas, the tragic hero of one of India’s best-loved films. Both men turn to whores who reveal themselves to be more than pretty faces; both fight their way through life in a haze of alcohol and fury. No element of The Outcast reminds me more of Bollywood than the quality of its violence. Lewis faces off against a sneering rival who insults his dead mother; against a pack of boys itching, like trained dogs, for a fight; against Dicky Carmichael, who derives his only excitement in life from abusing others. At first Lewis prevails physically, but as the novel progresses, his victory becomes spiritual; he not only endures the blows of his attackers, but finds release in them. The Passion of this new Christ-figure culminates on the day he commits the crime that will land him in prison for two years: “Ed punched him in the stomach and winded him, and Tom hit him in the side of his face and his head felt like it was exploding, and he loved it.”

That Lewis is not just the town’s outcast but its scapegoat, in the full meaning of the word, is underscored unequivocally just before the novel’s dramatic conclusion. All the town’s hypocrisy and fear are foisted upon him through the symbolic personage of Dicky, and he welcomes this catharsis though it will leave him broken and bleeding. “Why don’t you?” he says repeatedly as Dicky lunges at him. “Go on, do it.” When he does not move to protect himself, we know his apotheosis is imminent : “He had blood in his mouth, Dicky saw his teeth were colored with it, but he didn’t put his hand up to check, like a normal person would.” And sure enough, what Lewis does with the fruits of this violence has the potential to save his persecutors from themselves.

All this may suggest that The Outcast delivers nothing but Good and Evil, pitched against one another as they are in Bollywood and the Bible, but Jones’s novel diverges from these elemental narratives in crucial ways. Her characters, with the notable exception of Dicky, are complex and unpredictable. Their interactions with each other – Kit’s sister Tamsin’s puzzling flirtations with Lewis, Lewis’s stepmother’s roiling maternal-sexual attraction to him – are as richly subtexted and expertly paced as those in an Ishiguro novel.

Jones’s rough-hewn prose vividly renders Lewis’s inner life even when he himself struggles to understand his motivations. This prose seemed awkward to me at first, stumbling and stretching to get around ideas that could be conveyed more gracefully in fewer words, and seeming to resort too readily to passive constructions: “There had been partings and reunions that had made the sound of the trains in the distance, as they were heard from the houses, invested with emotion, not just an everyday sound like before.” Yet the language takes on a blunt rhythm of its own as the narrative progresses, and its complete lack of artifice yields surprising insights, especially into the nebulous terrain of the body. Lewis touches a woman’s arm to feel “the skin and the rest of her under the skin”; after Dicky beats him up and leaves him to bleed on the carpet, Lewis notes that his teeth “felt loose in his head, but his tongue couldn’t feel looseness,” then puts a hand to his hurt eye and finds that “it was very big, it wasn’t a hole or a gap or something frightening, it was just too big and sticky.”

Perhaps The Outcast isn’t for everyone. In particular, I predict some hesitation among American readers before its clunky prose and melodrama. Readers who feel unease in the absence of irony are advised to look elsewhere, but those who are not afraid to set aside fashionable cynicism and lose themselves in a bold, old-fashioned story might find themselves crying, as I did, over its last few pages.