“Give me a girl at an impressionable age,” Muriel Spark’s Jean Brodie said, “and she is mine for life.” Something sinister, about being given to, or taken over by Miss Brodie at an impressionable age. But, at the impressionable age of eleven, I had the great good fortune to fall under the spell of teacher Sally Nash. From the first day forward, I was hers for life, though she had no intention to hold an impressionable girl in thrall. She taught us to discover, investigate, explore, and create. An educator in the classical sense of the word, she drew us out.

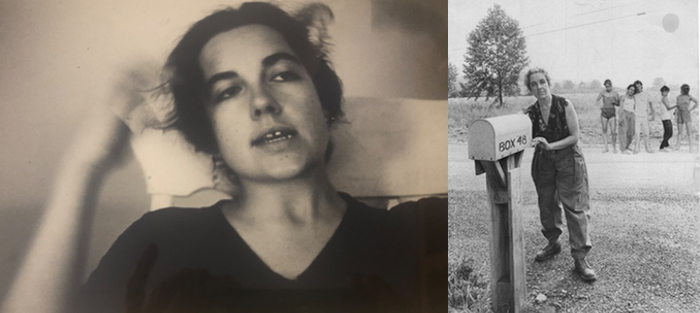

Sally introducing students to Indian cuisine, approximately 1967

I had just returned to Green Acres School, after a year in a British girls school during my father’s sabbatical at Oxford. There everything had been rigid; we even did “Maths” in ink, making mistakes indelible. At least as an American I was exempt from taking the national Eleven-Plus examination that would determine my classmates’ future: trade school or university. But every time I opened my mouth, my American accent embarrassed me. Always a good student, there I felt uncertain; I won the school poetry competition and overheard whispers that the poem couldn’t have really been mine.

So I was relieved to be back, but uncertain where I would fit in to my class, among my friends. And who was this new teacher? Sally was young—younger than we knew, not long out of college. She was compact, and strong. She walked and gestured like the dancer she was, every move, even raising her arm to write on the chalkboard, imperious, definite, sharp. She wore simple velveteen jumpers, like tunics, over black tights and black jerseys, always ready for a dance rehearsal.

Sally worked us hard, took us seriously, but the classroom was often fun, marked by her creative spirit. Studying Egyptian civilization, we excavated a trash basket, tasked to write about our layers of discovery as archeologists, anthropologists, piecing together a culture from its remains.

Next came Ancient Greece, and we put on Antigone. We practiced every day for what seemed like months. Perhaps it was. Probably the full-length production felt like years, to our audience. Some of us never quite learned our lines, which didn’t trouble Sally—she understood strengths and weaknesses. King Creon read from his mimeographed script and, miraculously, so did blind prophet Tiresias. She taught us about suspending disbelief.

And about the beauty of language. We used the translation by Maurice F. Neufeld, who had been her teacher. The chorus danced, of course, as they might have in Sophocles’ time. All of us danced during rehearsals. Sally beat her drum and we lunged to the beat across the cold tile floor of our practice space, reciting in unison:

Many things are wonderful, but none more wonderful than Man.

Over the white of the sea he goes, driven by the stormy south wind of winter.

<hr/ >

We called all our teachers by first names at Green Acres, so she was Sally, but there was no question with her who was in charge. Every week she presented each student with an individual contract, personalized assignments and tasks designed to develop our strengths and improve our weaknesses. She met with each of us, one on one. Serious meetings to review the contract. She signed; the student signed. Sally expected the best of us and we tried to deliver.

Sally Nash

I’ve always had what my great aunt called “the gift of gab.” Not meaning chatter, I skew to shy, but rather the gift of putting words together. Yet Sally didn’t let me coast; she was a dancer accustomed to a discipline that requires incremental exercises to build on talent. So each week a writing exercise appeared on my contract. I remember learning about metaphor and simile, their uses and powers. Write a description of seeing the world as though everything in it is in just shades of one color. I chose green. Bottle-green, I said. You can do better, she commented. Coke bottle green, I revised. Better, she said.

Sally had a wry smile, a high forehead, and brilliant gray eyes beneath bold black eyebrows that had a life of their own. She teased us that she was a witch, raised one eyebrow in a perfect arch, flared her nostrils, and thrilled us with a daring glance. And sometimes on those rainy days, as any good witch should, she told fortunes. She foretold I would be a writer. I re-read my sixth-grade journal this summer—hard drive for my memory. “I will have a book published, next spring,” I had written, supremely confident, believing in her belief in me. In fact, it took me more than forty years after leaving Sally’s classroom to fulfill what she had promised me I could do.

Sally’s gone now. I learned it in the dark days of December, months after her death in May. Another stealthy departure during this pandemic year. Poet Seamus Heaney remembers a mentor “with the special gratitude we reserve for those who have led us towards confidence in ourselves.” I owe Sally that gratitude. She was my sixth-grade teacher, discerning before I knew it that writing was my invisible power.

What interrupted me? Why did it take forty years to fulfill her prophecy?

Partly, the necessary, meaningful demands of work as a psychotherapist—listening to stories. Partly the rewarding, messy, creative process of raising kids.

But perhaps I held back also, unknowingly, out of giving too much credence to my internal doubts, listening too closely to external critics. There are good witches and bad, good teachers and bad. I can still see the red ink on my first college essay: “This is like getting dressed in a fancy dress to clean the oven.” Figures of speech can be powerful. There are good spells, and bad.

Finally, I came back to where I’d started, or meant to start. What brought me back? The fall of the towers on 9-11, the coincidental deaths of my parents soon after. I’d been reminded that time would run out for me too, sooner or later. So I began writing again. Exercising those muscles is like dancing. Practice, travel across the floor, the page, faster and smoother. If you’ve had a teacher believe in you, you begin to hear her drum beat in your mind, you hear your own voice once more. The confident voice of that girl who wrote in her journal, “I will have a book published, next spring.”

I had kept in touch with Sally, over the years. Seen her occasionally after she built the choreographer’s retreat center deep in the Blue Ridge Mountains. She lived in the house she’d designed, her space upstairs, looking out at the mountains, a dance studio below, a cottage for visiting dancers across the way.

When my first stories began to be published, I made a pilgrimage to tell her, bringing copies of the journals. She asked me to stop at Trader Joe’s in the Virginia suburbs for a case of “Two Buck Chuck.” We drank wine and talked. She wasn’t dancing any more. A brain tumor’s slow insidious growth had accelerated. Sally had taught herself to paint. I stayed the night in the guest house, waking early to continue work on the draft of what would become my first novel, inspired more than a little that morning by the sense of her creative spirit across the way.

When my first stories began to be published, I made a pilgrimage to tell her, bringing copies of the journals. She asked me to stop at Trader Joe’s in the Virginia suburbs for a case of “Two Buck Chuck.” We drank wine and talked. She wasn’t dancing any more. A brain tumor’s slow insidious growth had accelerated. Sally had taught herself to paint. I stayed the night in the guest house, waking early to continue work on the draft of what would become my first novel, inspired more than a little that morning by the sense of her creative spirit across the way.

When my novel was published, I came again, bringing her a copy of the book. Sally’s eyes were failing. She could no longer read; had a basket over-flowing with recorded books beside her chair. I wish I had asked to stay the night in the guest house, read aloud to her the book she had foretold.

After that, I visited about once a year, sometimes on my way home from an artists’ retreat a few hours further south in the Shenandoah Valley for musicians, painters, and writers—but no choreographers. Sally’s Workspace is sui generis. We talked about my work in progress, and her work—the hard work of hanging on. But dancers are sturdy, accustomed to pain and difficulty.

On what would prove to be the last visit, May of 2019, I came with my sixth-grade classmate, my lifelong friend. Sally was wheelchair bound; producing speech had become hard. We interpreted or intuited what she said. Determined and commanding as ever, Sally made it clear when we understood, and equally clear when we failed. She was still our teacher. Teaching us with her audacious courage. Teaching us by how she lived.

Sally’s gone. But I hear her drumbeat, propelling me across the floor, across the page. Many things are wonderful, but none more wonderful than Sally.