About nine months after I heard Steven Millhauser’s incendiary reading at The Story Prize, his story “A Voice in the Night” arrived in the December 10, 2012 New Yorker. It starts with the title conceit: God’s voice calling the boy Samuel, who thinks the old temple priest Eli must be shouting his name in the darkness. I settled into a straight retelling of the biblical story.

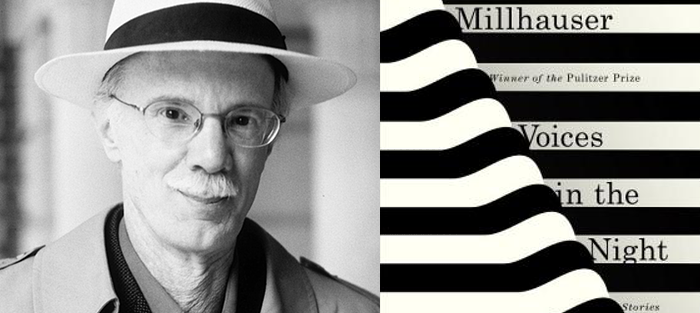

Steven Millhauser © Beowulf Sheehan

Wait. Suddenly we’re in Stratford, Connecticut in 1950 with a boy lying awake one hot summer night thinking about the Samuel story, which he heard in Sunday school that afternoon. He’s listening, too. I almost felt he’d been reading the first part of the Millhauser story beside me in bed.

The story jumps again. We’re with “the Author,” also wakeful in the dark. Is it Millhauser himself, is that what we’re to assume? The piece refracts the same situation, the same story, through time and layers of meaning. Somewhere by the second page, I realized my early questions hardly mattered. Something marvelous and magical had begun to unspool across the page and hang-ups about structure or how much autobiography a reader could assume were wholly irrelevant.

“A Voice in the Night” gives a very compelling argument for a piece of literature providing its own explanations and justifications. Just as books like Lolita or The Waves stand as works that threw away the old charts and drew new maps; “A Voice in the Night” defies description. It blew the lid off how I had been viewing fiction and storytelling for quite some time without realizing my mental rut. A story can be anything—anything true and compelling. Read it for yourself.

Extra

- Read Millhauser’s “A Voice in the Night,” published in the New Yorker.