Daphne du Maurier consented to have her most famous work co-opted by powerful men in the movie industry—Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds and Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now being the prime examples—but both of these admittedly excellent films come from stories where du Maurier opted for a masculine lens through which to convey a self-reflective critique—distrust in one’s spouse and family as a sign of personal weakness, a theme only faintly discernible in Hitchcock’s and Roeg’s muscular adaptations. Another side to this coin exists, though: when our paranoia in our partners and friends is warranted, when the men in command are actually up to something, usually when they are “at the office,” machinations which the women in their lives, confined at home in their post-WWII domestic roles, can hardly begin to fathom.

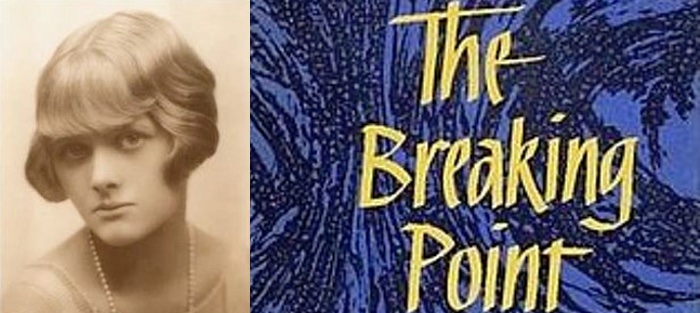

In “Blue Lenses,” originally published in 1959 in The Breaking Point, the main character, Marda West, is constrained not only by conventions of gender and era but also by her recuperation from a complicated procedure to address her failing vision which prevents her from leaving the hospital bed she has lain in for weeks. Temporarily blind, Mrs. West’s needs are seen to by an array of nurses, doctors, and surgeons, while her husband, Jim, befitting his stereotype, is heard mostly through telephone conversation where he is too busy and distracted at work to attend to his recovering wife’s suspicions (or delusions).

In “Blue Lenses,” originally published in 1959 in The Breaking Point, the main character, Marda West, is constrained not only by conventions of gender and era but also by her recuperation from a complicated procedure to address her failing vision which prevents her from leaving the hospital bed she has lain in for weeks. Temporarily blind, Mrs. West’s needs are seen to by an array of nurses, doctors, and surgeons, while her husband, Jim, befitting his stereotype, is heard mostly through telephone conversation where he is too busy and distracted at work to attend to his recovering wife’s suspicions (or delusions).

Mostly, Jim tells Marda she needs rest, and that he will not keep his infrequent visits overly long so she can get this rest. When he does come, at night after work, he seems to spend more time conferring with the night nurse, Nurse Ansel, in the hallway, whispering and conspiring, than actually speaking with his wife. And in fact, we learn that Nurse Ansel, the calm, soothing voice that arrives at 8 p.m. every evening, liberally administering morphine and comforting Marda when she becomes agitated, will return home to live with her and Jim for a week or two after Marda leaves the hospital, an arrangement Marda initially desires but eventually comes to question: how did she ever get this idea, and why does Jim agree so readily—almost as if the idea had not been entirely hers?

This paranoia is heightened when the blue lenses upon which the story is titled make their appearance. Her stay at the hospital nearing its conclusion, Marda’s bandages are removed and her eyes fitted with a set of temporary lenses that enable her to see the world again, albeit through a blue hue. Objects appear as they are, and so does her own face in a mirror. But there is a catch, a move du Maurier makes that transforms the story from a claustrophobic exploration of gender confinement and powerlessness to something stranger and more sinister: through her new temporary lenses, Marda can see other human beings as the animals they truly are.

The metaphor is hardly subtle. The benign but annoying day nurse, Nurse Brand, is a cow. Her surgeon, Dr. Greaves, a fox terrier. The house doctor is another dog, an Aberdeen. At first, Marda is convinced that they are wearing masks, that it is part of some incomprehensible, elaborate plot to make her go insane. But when she sneaks out into the hall (one of only two times in the story that she leaves her bed) or looks out her room’s window at the traffic on the street, she notices that all human beings—a fellow patient who is a bear, a cab driver who is a frog—sport their own animal head.

The suspense in “Blue Lenses” is ingeniously negotiated by du Maurier and as readers, we are left to await (and dread) Jim and Nurse Ansel’s appearance later in the evening, Jim after he finishes work and Nurse Ansel when she arrives for her graveyard shift. Will they be animals as well—we strongly suspect so—but more importantly, what animals will they be, benign or predatory? This is an important test for the story, a slight rending of the seam existing between our experience as readers and Marda’s. Despite all evidence, she still clings to the hope that Jim will turn up human, a white knight who will save her from the hospital and its mad staff of lunatics and plotters. We do not share in this belief: we fear the “animals” who will oversee Marda’s care once she returns home will be worse than a cow or dog, and this fear proves well-founded—in this story and in her body of work overall, du Maurier delivers what scares us most: that when we are at our most vulnerable is when the people to whom we entrust our care are most out to get us.

Jim, it turns out, is a vulture with a “blood-soaked beak” who is conniving to steal Marda’s trust by forcing her to sign papers she cannot read, on the pretense that she may be “ill” or “away.” Seemingly in cahoots with Jim is Nurse Ansel, a slithering snake with an adder’s “V” for a head, proffering sedatives that keep Marda docile and compliant. On her last evening, in a climactic act of defiance, Mrs. West only pretends to take her sedative, and when Nurse Ansel is called by another patient, she quickly dresses and escapes. In the dead of night of the “real world,” however, Marda finds no relief, her experience outside just as frightening as it was in:

…It came to her once again that there was no one, no one at all: because the couple passing her now, a toad’s head on a short black body clutching a panther’s arm, could give her no protection, and the policeman standing at the corner was a baboon, the woman talking to him a little prinked-up pig. No one was human, no one was safe, the man a pace or two behind her was like Jim, another vulture. There were vultures on the pavement opposite. Coming towards her, laughing, was a jackal.

Marda collapses and upon awaking, finds herself back in the hospital, properly sedated this time. There will be no more escapes, no more “episodes.” In fact, she discovers that her blue lenses have been replaced by her permanent ones. Now she can see color, and—hallelujah!—everyone looks “normal” again, no longer bearing their terrible animal’s heads. But Marda cannot ever forget—her husband is a vulture, her caretaker a snake, and she is going home with them. Her situation is emphasized at the last by du Maurier in one of the twists she is renowned for: with one last glimpse in a mirror, Marda realizes that although everyone else appears human, the eyes that stare back at her are those of a helpless doe “wary before sacrifice,” her head now a “timid deer’s… meek [and] already bowed.”

“Blue Lenses” is a story that haunts, much like the work of du Maurier’s literary predecessors Poe and Gaskell, and her contemporaries on this side of the Atlantic, Shirley Jackson and Margaret Millar, all masters of what is commonly referred to as “the macabre.” But this denomination is reductive—what we can learn from du Maurier is that it is most often from the expected that we experience our greatest fear, particularly if our perspective is that of the Other. The constant paranoia created by a marginalized social positioning inculcates in beings a sense of helplessness, the inevitability of being crushed by a system in which your role is always minor, always invisible. Du Maurier composed “Blue Lenses” in the Cold War era, and her message proves oddly prescient—increasingly, we are scared less of the unknown, as our prehistoric ancestors may have been, and more of the known and the familiar—those around us, our friends and family, and the social institutions—schools, hospitals, churches, and government—upon which we so much rely. But one balm to this fear is to walk straight into it–read and love stories like “Blue Lenses” at night, in bed, before turning off the lights, preferably out loud to your beloved.