When “Hill of Hell” by Laura van den Berg came out last year in the spring issue of the Virginia Quarterly Review, I mentioned it in passing to my friend Jenn. “That story,” Jenn said, “I don’t know—that story got to me.” As VQR’s art director, Jenn reads and chooses artwork for each piece the magazine publishes. Her tastes are discerning. She doesn’t gush. So, when she expressed her regard for van den Berg’s story, it stuck with me—not only because I respect her opinion, but also because “Hill of Hell” got to me too.

The story evokes big, unsettling questions—about the hidden wants we hold inside and our level of complicity when those wants become reality, the concealment of our inner lives to those closest to us, our perception of these loved ones and our ability (or inability) to recognize their personal transformations, and how this precludes (or maybe doesn’t preclude) true intimacy with others.

This sounds like a lot. And it is. But van den Berg presents it all with remarkable economy. At the beginning of the story, the first-person narrator, who immediately draws the reader—as confidant—into the narrative, describes a train ride with an old friend, saying, “We had sailed through the small talk and were ready for the blood and guts.” And this is precisely what the story does. At the very outset, the narrator and her friend each divulge the “worst thing” that has happened to them since their last meeting.

These revelations bring us straight to the story’s first big proclamation, voiced by the narrator’s companion: “‘The big alone,’ he said. ‘That’s all any of us has in the end. Nothing can protect us from it, not careers or children or spouses or money or lovers.’” Later, in one of the story’s deft circling patterns, the narrator returns to the words of her friend, explaining:

This was how I had come to understand the big alone—the way we are walled-in by our secrets and the implacability of our judgements. The big alone had little to do with physical company; rather, it was a matter of understanding, and where understanding broke down.

Throughout the piece, van den Berg drops these boulder sentences—lines that force the reader to stop and question the workings of human relationships, the nature of our existence.

Though the story is short and reads quickly, these weighty statements feel genuine and not without due precedence. This is accomplished, in part, because story spans a broad expanse of time. After the initial encounter between the narrator and her friend, the story jumps ahead multiple decades, into the narrator’s second marriage, narrowing in on the death of her adult daughter. Who knows how much boring stuff happened over the years? Not the reader, thankfully, because van den Berg skips it.

In this second section of the story, the compression of time is remarkable. The daughter’s entire life is condensed into a single paragraph. She goes from being “a sleepless and squalling baby” to a recovering addict “answering phones at a veterinarian clinic.” These details allow the character to materialize despite the brevity with which she is portrayed. The relationship between the daughter and her parents can be felt by the voice of the narrator: “The sober version of my daughter turned out to be just as prone to petty cruelty and deception.” In this single paragraph, we see not only the character of the daughter, but also the complicated relationship between the daughter and her parents—a relationship made more complex now that she is dying.

In this second section of the story, the compression of time is remarkable. The daughter’s entire life is condensed into a single paragraph. She goes from being “a sleepless and squalling baby” to a recovering addict “answering phones at a veterinarian clinic.” These details allow the character to materialize despite the brevity with which she is portrayed. The relationship between the daughter and her parents can be felt by the voice of the narrator: “The sober version of my daughter turned out to be just as prone to petty cruelty and deception.” In this single paragraph, we see not only the character of the daughter, but also the complicated relationship between the daughter and her parents—a relationship made more complex now that she is dying.

Though the story packs this heavy-hitting material into a small space, it is not without light. The descriptions of how the daughter chooses to prepare for death, attending “death cafés” and enlisting a “death doula,” are almost humorous. The dopey train conductor who “beams” over his unattractive baby to unsuspecting passengers adds surprising levity. And in the end, though the narrator admits that she may never know the thoughts of her husband, we are left with the image of their warm embrace.

What I think I love most about this story is how its admissions of dark wishes and needling uncertainty allow the reader to silently align with the narrator and air their own secret thoughts within the space of the story. Maybe this is why Jenn’s words stuck with me. The story is about connection, about how deeply we can truly know another. What I have come to know is that reading (and writing) is an intensely intimate act, capable of forging a connection where other modes of communication fall short. And when a piece can affect multiple readers, maybe in similar ways, a connection is made not just between the reader and the text, but also—like some sort of positive contagion—between readers as well.

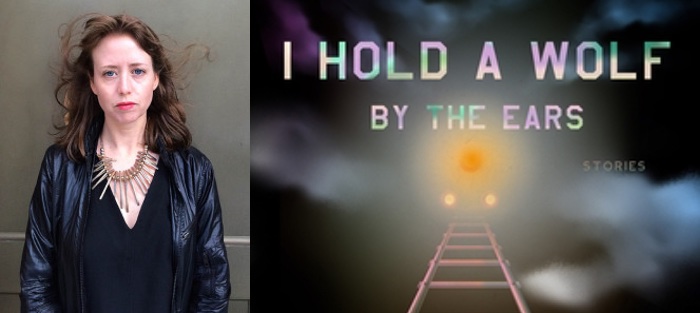

“Hill of Hell” can be found in Laura van den Berg’s forthcoming collection of short stories I Hold a Wolf by the Ears, out this July from FSG.