A loving marriage. Healthy children. A thriving career. Where’s the story in that?

We all know Paradise is dull. No conflict. Except, of course, the potential for expulsion.

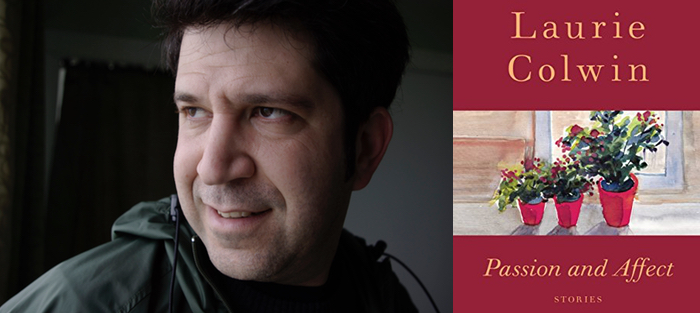

“The Water Rats,” from Laurie Colwin’s first collection, Passion and Affect (Viking Press, 1974), is one of the few stories I’ve ever encountered to explore the terror of happiness. It begins with a simple premise: Max Waltzer, living a blissful life on the Long Island Sound, discovers that water rats are living where his children often swim. Concerned that poison might contaminate the water, he asks a friend to bring hunting rifles. They shoot four of the rats, and the rest disappear. But his friend warns that they might come back, that Max should remain vigilant.

Nothing else happens in the story; the rats don’t reappear, and no other drama replaces them. In lesser hands, Max might be made to suffer calamity: illness, accident, crime, divorce. But Colwin—one of the very best story writers of the 70s and 80s, and now nearly forgotten—understands that all it takes to crack the foundation of bliss is the mildest tremor.

Once you know you can be kicked out of Eden, it becomes a place of utter dread; you’re constantly waiting, looking over your shoulder, wondering if today will be the day.

Colwin makes clear to us early in the story that Max does not take his life for granted. He is rich now, but he didn’t start out that way. He knows what happens when desire ends in failure, having observed his father, the owner of “an unsuccessful glass bottle factory to which he had been devoted.” As a result, he appreciates his good fortune. Six years after buying it, “Max was still in love with the house… He was in love with his wife and his babies. Looking at his sons, watching their bright heads move as they played, caused him to count his blessings with a sense of pain: he did not understand why all this was his, and he treasured it.”

Already we hear the “pain” in his fulfillment. He recognizes how precious it is, how tenuous, and how vulnerable to the unforgiving world around him. No matter how many times I read these lines, I suffer a similar pang, equally bewildered by my own comfortable life, my happy marriage and lovely child, my peaceful home and rewarding job. How can I sleep at night knowing how much I’ve got to lose?

Max’s contentment is already fragile by the time the water rats arrive, and their brief intrusion shatters it for good, though he doesn’t yet understand why. In the weeks and months after he and his friend clear them out, he searches for them constantly, waiting for their return. He has no particular reason to believe they’ll come back and does not know “what was driving him out of his bed, into his clothes, and out to the cold Sound. It wasn’t restlessness, but he couldn’t sleep. He was being compelled.” The word Colwin uses again and again to describe his action is “patrol,” as if he has become a soldier: in December, when it would have been too cold for rats to be out, he “patrolled the water’s edge three times a day,” and “as the winter went by, Max’s patrols got longer,” lasting two hours or more. Only when he is out by the water, carrying his friend’s shotgun, does he experience “a sense of calm,” coming to believe “what he was doing was right … a part of his life, like getting up in the morning and going to work.”

Max’s contentment is already fragile by the time the water rats arrive, and their brief intrusion shatters it for good, though he doesn’t yet understand why. In the weeks and months after he and his friend clear them out, he searches for them constantly, waiting for their return. He has no particular reason to believe they’ll come back and does not know “what was driving him out of his bed, into his clothes, and out to the cold Sound. It wasn’t restlessness, but he couldn’t sleep. He was being compelled.” The word Colwin uses again and again to describe his action is “patrol,” as if he has become a soldier: in December, when it would have been too cold for rats to be out, he “patrolled the water’s edge three times a day,” and “as the winter went by, Max’s patrols got longer,” lasting two hours or more. Only when he is out by the water, carrying his friend’s shotgun, does he experience “a sense of calm,” coming to believe “what he was doing was right … a part of his life, like getting up in the morning and going to work.”

But this calm eventually dissolves. His need for security in the face of the unknown becomes insatiable. His family goes on vacation to Bermuda, but he opts to stay home, patrolling the water. As soon as they leave, “fear assailed him… He knew life contained profound miseries: something could happen to his children.” He pictures the plane crashing, his sons getting sick or being kidnapped, his wife leaving him. And from there his imagination undoes him:

This terrible set of possibilities attacked the shell of his life and put an edge on his happiness. But it seemed to him that life was teaching him the meaning of true happiness, and the secret was that it was difficult and terrifying to be blessed… Life had put everything lovely into his hands and had not taken it away. He knew it was not impossible that things would stay this way, but looking at the world he knew it was improbable. He wondered why the coin of his life didn’t turn, show its reverse side and leave him stranded with empty hands.

The abundance of good in his life leaves Max on the edge of madness. During his first moments alone in the house he realizes that “if life were to reverse itself and everything he loved was taken away from him, it would resemble this thick, empty silence.” He can’t imagine living this way for a week, much less forever. He patrols the Sound again, takes aim at a raccoon, then hurls the gun into the water. Back in the house, he picks up the ringing phone, his wife calling to let him know they’ve arrived safely. Before hanging up she asks if he has everything he needs. And the story ends with what strikes me as one the most chilling lines of dialogue in all of contemporary fiction: “‘Yes,’ said Max. ‘Everything.’”

He has everything he needs, and it is killing him.

“The Water Rats” is a fierce and honest retelling of the story of Job in the era of psychology, God and Satan making bets entirely in Max’s head. Without constructing external drama to strip Max of his comfort and security, Colwin reveals just how insidious happiness can be, how it brings out our worst instincts, especially when we try desperately to preserve it. In doing so, she also makes us see the trouble with Paradise: the moment we recognize we’re in a perfect place we never want to give up, it’s already gone.