This past August, I went to Tbilisi, Georgia for two weeks. Many people asked me why my girlfriend, Oksana, and I wanted to spend our only vacation of the year staying in an attic room in the hundred-degree weather of a small, remote, post-Soviet city. I told them many things: that it was a cheap destination; that I wanted to drink bottle after bottle of sweet Georgian wine; that Georgia is the most beautiful country in the world; that Oksana wanted to visit the city where her grandfather had grown up; that she wanted to visit the grave of her great-grandfather, a World War II hero, in the city’s neglected Russian-Jewish cemetery. All these things were true. But the real reason I went is because of the first sentence of an Isaac Babel story, “My First Fee”: “To live in Tiflis [Tbilisi] in the springtime, to be twenty years old and not to be loved is a terrible thing. It happened to me.” This story has had a profound effect on my writing life, and I wanted to inhabit the story’s setting, however briefly.

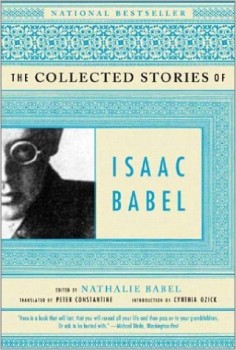

“My First Fee” was written in the 1920s, and is apparently an expansion of an earlier story called “Answer to an Inquiry.” It went unpublished during Babel’s lifetime (he was murdered on orders from Stalin in 1940), not appearing in print until the early ‘60s, when it was published in New York, first in Russian, then in an English translation. I first read the story in the early 2000s, in an undergraduate Modern Jewish Literature course. Fittingly, the class was taught by Val Vinokur, who is currently working on a new translation of Babel’s stories. My Russian is extremely limited; I can’t read anything more than a sign or maybe a menu. I’m not positive which translation we read in class, but it might have been Peter Constantine’s. Here, I am quoting Max Hayward’s translation.

The narrator of the story is an inexperienced young man working a bureaucratic proof-reading job. Tortured by lust, he solicits a prostitute he is infatuated with. Before the woman, Vera, sleeps with him, he has to accompany her around Tbilisi as she makes her rounds and spends his money. Finally, they go up to Vera’s room. There, in the prostitute’s bed, the narrator spins a sordid tale about having been the adolescent lover of an older Armenian man in Baku. Vera is moved by the story, and comes to consider the narrator a “sister” prostitute, rather than a john. They spend the rest of the night making love, with the thirty-year-old prostitute tutoring the young man in the erotic arts. The narrator boasts that he, “learned secrets you will never learn” and “experienced a love you will never experience.” In the morning, Vera insists on returning the narrator’s money, as she did not consider the sex transactional. From his perspective, this money is the first fee he has earned for writing a story. Vera is his “first reader.”

I learned a few secrets from the story myself. As the narrator composes his story, he discovers what his reader will and won’t buy. His success starts with his story’s premise. “If I had given less time and thought to my craft,” Babel writes, “I should have made up a hackneyed tale about being the son of a rich official who had driven me from home …” Luckily, he avoids the pitfall of this contrived plot, observing, “A well-devised story needn’t try to be like real life. Real life is only too eager to resemble a well-devised story.” He continues to build the story’s authenticity, first by playing against Vera’s expectation that the older Armenian will be villainous, and then by adding the specific detail of unbacked promissory notes. Conversely, the narrator momentarily loses Vera’s attention when he mentions a church warden. Seeing her reaction, he admits to himself that the warden “was filched from some writer: he was the invention of a lazy mind which can’t be bothered to produce a real live character.” He finishes strong, arriving at a convincing ending, with the Armenian’s death and his own arrival in Tbilisi.

I learned a few secrets from the story myself. As the narrator composes his story, he discovers what his reader will and won’t buy. His success starts with his story’s premise. “If I had given less time and thought to my craft,” Babel writes, “I should have made up a hackneyed tale about being the son of a rich official who had driven me from home …” Luckily, he avoids the pitfall of this contrived plot, observing, “A well-devised story needn’t try to be like real life. Real life is only too eager to resemble a well-devised story.” He continues to build the story’s authenticity, first by playing against Vera’s expectation that the older Armenian will be villainous, and then by adding the specific detail of unbacked promissory notes. Conversely, the narrator momentarily loses Vera’s attention when he mentions a church warden. Seeing her reaction, he admits to himself that the warden “was filched from some writer: he was the invention of a lazy mind which can’t be bothered to produce a real live character.” He finishes strong, arriving at a convincing ending, with the Armenian’s death and his own arrival in Tbilisi.

Though referred to in rapturous language, the sexual experience is ultimately vague and secondary. “My First Fee” is primarily a story about how to write a story. Babel walks us through the steps of crafting a plot, developing believable characters, adding detail, and revising to eliminate weak or unbelievable sections. I learned as much from reading—and rereading—this story as I did from many of the MFA workshops I later attended. What’s more, the story told me what my life would be like as a writer: “All this was a long time ago,” Babel writes in the story’s conclusion, “and since then I have often received money from publishers, from learned men, and from Jews trading in books. For victories that were defeats, for defeats that turned into victories, for life and for death they paid me trifling sums.”