William Maxwell’s “Over By The River” is dangerous. It will fool you into thinking you can become a writer. In this not-so-short story, life appears to rise effortlessly from the page. You will say—”That is it!” You will think—”All I must do is write it down!”

As if to tease the aspiring writer, Maxwell does just this. Halfway through the narrative, George Carrington’s third walk along New York’s East River unrolls like “a Chinese scroll, from right to left,” in a list of items witnessed:

The tugboat Chicago pulling a long stream of empty barges upstream

A little girl feeding her mother an apple

A helicopter

A kindergarten class, in two sections…

There are thirty-two items in George’s list. But what a list! In the hands of a lesser writer this might be dull. In the hands of William Maxwell it is somehow poetry. The final item is not something seen, but something thought:

Who said: Happiness is the light shining on the water. The water is cold and dark and deep.

The character of George Carrington asked this question forty-two years ago. In answer today, Google suggests William Maxwell.

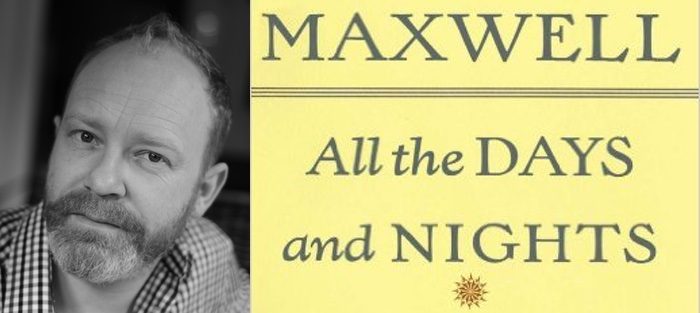

William Maxwell’s story persuaded me I wanted to write. I still have the same copy, and looking back some twenty-one years after I first encountered “Over By The River,” I can see there is much for which I should thank Maxwell (as well as blame).

I came across the stories of William Maxwell at an age when I valued the cover of a book more than its contents, or more accurately, valued the imprint. It was 1996, and I was twenty. I had once bought a good book published by The Harvill Press. (I think it was Jaan Kaplinski’s The Same Sea in Us All.) I can’t remember much about Kaplinski’s book now, or the other Harvills: Henry Green’s Surviving, or Ismael Kadare’s The Palace of Dreams. But what was truly memorable and wonderful about The Harvill Press was the standing leopard they printed at the top of every spine.

I came across the stories of William Maxwell at an age when I valued the cover of a book more than its contents, or more accurately, valued the imprint. It was 1996, and I was twenty. I had once bought a good book published by The Harvill Press. (I think it was Jaan Kaplinski’s The Same Sea in Us All.) I can’t remember much about Kaplinski’s book now, or the other Harvills: Henry Green’s Surviving, or Ismael Kadare’s The Palace of Dreams. But what was truly memorable and wonderful about The Harvill Press was the standing leopard they printed at the top of every spine.

The spine itself was set off by bands that I think were colored for the geographic area of the writer’s origin: Europe, North America, South America, and the Far-East. Together with the leopard, this had a marvellous effect on my multiplying book shelves. As well as being aesthetically pleasing, it created the impression of a man not only well read, but well-travelled. The man I wanted to be. Our books, as well as saying something about who we are, are an expression of the lives not led, the roads not taken. They are a connecting material. And in some ways, this is what Maxwell’s story is all about: connections.

There is an irony in opening Maxwell’s short story collection in my middle-age and encountering in the words of his preface, a man who also found the influence of a book’s cover irresistible.

Maxwell, the future fiction editor of The New Yorker, describes how in 1933, at the age of twenty-five, he concocted a plan to board the schooner of JP Morgan with a letter of introduction to the captain.

I had meant to go to sea, so that I would have something to write about. And because I was under the impression gathered from the dust-jacket of various best sellers, that it was something a writer did before he settled down and devoted his life to writing.

The tension between living and writing can be strained. The more you write, the less you live, and the more scarce the resource of experience. But William Maxwell mined both the upper-middle-class of New York and the rural hinterland of his Midwest childhood with the same careful skill Alice Munro navigates the depths of Lake Huron.

I had no idea that three-quarters of the material I would need for the rest of my writing life was already at my disposal,” he writes in the preface, “My father and mother. My brothers…affectionate aunts, friends of the family, neighbours white and black…the look of things. The weather…the suede glove on the front hall table, the oriole’s nest suspended from the outer tip of the upper-most branch of the elm tree.

Putting down what you see as accurately as possible is the foundation of our craft. Maxwell was a great witness. But the danger of “Over By The River,” as well as its genius, is that while its effect is effortlessness, it is a story in which much effort has been spent in breaking all “the rules.”

“The rules” are the tactics we recommend to ourselves and, if we teach, to aspiring writers. They exist to help us carefully build-up the powerful cliché of “the writing muscle”: stick with one point of view at a time; don’t mix tenses; use the language of the character, not the author; follow the story; keep a dramatic unity of place.

All these tactics can make writing, and reading, easier. Simple narrative strategies allow writers to focus on the main business of telling a story, or writing a good sentence. They are tactics most mortal writers need.

In “Over by the River,” Maxwell abides by none of this advice. I’m sure this is exactly why, as a student of creative writing, the story thrilled me the moment I read its first, slippery lines:

The sun rose somewhere in the middle of Queens, the exact moment of its appearance shrouded in uncertainty because of a cloud bank.

Had I submitted such an opening to class, it would have been plagued by the red interrogatives of the tutor. Why “somewhere”? Isn’t that a little vague? What am I supposed to see? Who is seeing the sun? Where are they? Point of view.

Questions not without reason. From such a sentence, the nineteen-year-old writer was likely to become hopelessly lost. By the time Maxwell wrote the story in 1974, he had applied the red pen to writers as accomplished as Eudora Welty, John Updike, and John Cheever, and knew exactly what he was doing.

The story holds together a few months in the life of an upper-middle-class family on Manhattan’s East Side. Maxwell’s pellucid sentences illuminate the lives of husband and wife, George and Iris; their daughters, Cindy and Laurie; maid Bessie; a junkie in Central Park; a vagrant woman; a primary school music teacher; a cook who commits suicide; and a disappointed socialite.

On the turn of a sentence, Maxwell occupies the point of view of every character. No one is denied agency, not even the city itself. Here the school teacher’s piano comes to life:

The ancient piano showed for the benefit of the empty practice room that it is one thing to fumble through the vocal line, guided by the chords that accompany it, and something else again to be genuinely musical, to know what the composer intended — the resolution of what cannot be left uncertain, the amorous flirtation of the treble and the bass, notes taking to the air like a flock of startled birds.

By this stage in the story, Maxwell has taught us how to read him. The school teacher is not mentioned in the scene with the piano, it is the piano to which Maxwell’s sentences attribute agency. There is no literal magic at work, we know the school teacher must be there, but by foregrounding the instrument, the reader is forced to see the everyday for what it is, a miracle. In this, lies the greatest trick of the story, and the technique allowing Maxwell to inhabit every point of view.

The usual dangers of moving swiftly from the perceptions of one character to another are reader confusion, and a growing sense that the lives of characters lack agency. It’s as if they only exist to be manipulated by the dead hand of the author. To mitigate these problems, “Over By the River” is full of compressions and elisions, rhetorical tricks which give life not just to the characters, but to the city itself. As George waits for his breakfast, “The Orange Juice was in no hurry to get to the table.”

The usual dangers of moving swiftly from the perceptions of one character to another are reader confusion, and a growing sense that the lives of characters lack agency. It’s as if they only exist to be manipulated by the dead hand of the author. To mitigate these problems, “Over By the River” is full of compressions and elisions, rhetorical tricks which give life not just to the characters, but to the city itself. As George waits for his breakfast, “The Orange Juice was in no hurry to get to the table.”

By giving agency to the city and its objects, Maxwell creates an equivalence between the material and the human. In this context, the story is truly about the connection between things, not one individual, or even just the connections between characters.

The opening sentence announces this. The sun in Queens is seen by no one, and everyone; it is seen by “the city.” Indeed, Maxwell’s favorite trick with a sentence trains the reader to elide the material with the abstract, the world of physics with the world of ideas.

The doormen of the Upper East Side “had put on with their uniforms a false sense of amiability.” The uniform is material, the amiability is abstract, but both are being “put on,” both marshaled by the verb.

When George sees a container ship, his thoughts become a material part of its description: “a tanker, freshly painted, and flying the flag of George had no idea what country until he read the lettering on the stern.”

Maxwell pushes this technique as far as he can without quite entertaining surrealism:

There were signs all along the river walk:

NO DOGS

NO BICYCLES

NO THIS

NO THAT

And of course, this is to do much more than to “just write it down.” It requires a sharp imagination, control of language, dexterity with sentences, and a real vision for what a story is “about.” Try these tricks because they look fun and not because your story truly needs them, and they will begin to pall. (Trust me, I know from experience.)

Here, Maxwell’s technique and form perfectly suit the function. Life for the Carringtons is the privileged and protected life of Manhattan’s wealthy. By making the city the sum of all human actions, and showing how our environment insists upon a life of its own, Maxwell depicts our tenebrous, delicate lives, and reminds us of how connected all things are.