The terrific title story of Rebecca Lee’s collection Bobcat and Other Stories (Algonquin Books, 2013) is, on one level, simply the story of an ordinary dinner party. The most dramatic, striking plot event of the story doesn’t occur until the concluding paragraphs. But from the start, the author employs various forms of tension to raise the stakes of the story, and she goes on to modulate the tension in a way that keeps the tone of the story both light-hearted and unequivocally serious. (Much like the dinner party itself turns out to be.) How does Lee so artfully control tension in “Bobcat”?

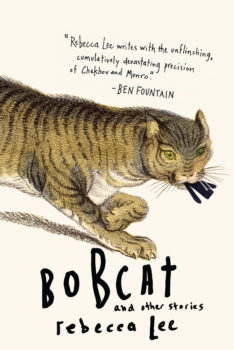

The terrific title story of Rebecca Lee’s collection Bobcat and Other Stories (Algonquin Books, 2013) is, on one level, simply the story of an ordinary dinner party. The most dramatic, striking plot event of the story doesn’t occur until the concluding paragraphs. But from the start, the author employs various forms of tension to raise the stakes of the story, and she goes on to modulate the tension in a way that keeps the tone of the story both light-hearted and unequivocally serious. (Much like the dinner party itself turns out to be.) How does Lee so artfully control tension in “Bobcat”?

To start, the title itself has an edge to it: it evokes the wild, it brings to mind a potentially threatening creature. Once we begin reading and realize the story is set in a Manhattan apartment building, the title raises further questions; it’s at odds with the opening scene. How will a bobcat play a role in this dinner party? Questions are a part of tension in a narrative (What will happen? How will this be resolved?), and the questions surrounding this story’s title raise the tension, slightly, just as we begin.

The first paragraph of the story sets the tone for the story as a whole. Subject-wise, the scene is peaceful, almost mundane. A married couple are preparing a terrine for a dinner party they are hosting that evening. But Lee’s language clues us in to turmoil beneath the surface. What’s interesting about her style is that we aren’t sure how much turmoil there really is—a wry wit runs through the writing here, as it does throughout the entire story. This mixed tone (tense as well as funny) serves the story’s suspense and ongoing questions well. Is this couple really struggling, or is it just pre-party stress? The first paragraph, from the first-person perspective of an unnamed narrator, sets the tone:

It was the terrine that got to me. I felt queasy enough that I had to sit in the living room and narrate to my husband what was the brutal list of tasks that would result in a terrine: devein, declaw, decimate the sea and other animals, eventually emulsifying them into a paste which could then be riven with whole vegetables. It was like describing to somebody how to paint a Monet, how to turn the beauty of the earth into a blurry, intoxicating swirl, like something seen through the eyes of the dying. Since we were such disorganized hosts, we were doing a recipe from Food and Wine called the quick-start terrine. A terrine rightfully should be made over the course of two or three days—heated, cooled, flagellated, changed over time in the flames of the ever-turning world, but our guests were due to arrive within the hour.

The tension here lies in the syntax and diction. An alternative first sentence might be, “We were making a terrine for a dinner we were hosting, and I felt sick.” But “It was the terrine that got to me” is more powerful, more curious. What got to her about the terrine—what does this mean? Uneasy language fuels the description of the cooking. “Queasy,” “brutal,” “devein, declaw, decimate,” “emulsifying,” “the eyes of the dying,” “disorganized,” “flagellated,” “in the flames.” Lee’s opening effectively raises narrative tension, while her dry humor modulates intensity.

The last sentence of the opening paragraph introduces another source of tension: time. The couple has less than an hour to finish the terrine and prepare for the arrival of guests. Using a clock to raise the stakes of a story early on seems especially effective in a narrative that does not reveal its protagonist’s most serious problem until much later. Within the first paragraph, we learn that the cooking isn’t going well, the party is about to start, and an unidentified trouble seems to be bubbling beneath the surface. And a bobcat may somehow be involved. How can we not read on?

In the next paragraph, Lee begins to introduce us to the characters by describing the guests before they arrive. This is an interesting strategy—rather than giving us backstory on each person at the moment they arrive on the scene, the narrator tells us about most of them (actually, warns us about them) before they come into the present-time action of the story. This technique seems another way of increasing pressure. The narrator shares her concerns about an invitee in advance, so the reader can’t help but wonder: What crisis might occur after that character arrives? The second paragraph begins: “Of the evening’s guests, I was most worried about the Donner-Nilsons, whom my husband called the Donner-Blitzens.” Again, the combination of anxiety offset by humor. The paragraph goes on to tell us of Ray Nilson’s well-known ongoing affair, which becomes a key plot line and source of suspense within the story. Does Ray’s wife know about the affair, and if not, should she be told at the dinner party?

Before the party begins, the narrator flashes back to earlier in the afternoon, recounting an argument between the herself and her writer husband, John. It’s again infused with both dark and light, so we aren’t sure: Is this reflective of a deeper problem in the relationship, or is it just everyday marital bickering? The language starts off muted, mild: “Truthfully, I was not pleased with his book. I had just finished reading it . . . and within the first forty pages, the protagonist had slept with three women, none of whom even remotely resembled me.” “Not pleased” doesn’t ring with anger; we don’t really suspect at first that this is a serious issue between them. There is tension here, but it is low. However, by the end of this section—which describes the narrator’s work as an attorney and introduces us to (warns us about) another soon-to-arrive party guest, Frances, the husband’s imposing editor—there is a slow ramping-up of tension, and we ultimately arrive at two sentences that are distinctly humorless: “The argument devolved from there. Certain themes got repeated—John’s intense solitude, my long hours, his initial resistance to commitment, my later resistance to marriage, and then at some point the reasons were left behind and we were in that state of pure, extrarational opposition.” The tone here is somber—all light-heartedness is gone—and it raises real questions for the reader about the state of this marriage.

But quickly the narrator lightens again, and the reader is back on unsure footing—maybe this isn’t a marriage in jeopardy? “I was pregnant and had read that high levels of cortisol in a troubled mother can cross the placenta and not only stress out the baby in utero but for the rest of its life.” Wryness, italics, exaggeration—all of these diffuse the tension. The argument is left behind as the party begins, although it lingers in the background for the reader.

During the party narrative that makes up most of the story, Lee focuses largely on the stories of the attendees. Ray Nilson’s adultery and whether his wife knows about the affair is a central, repeated question. Also, the narrator’s close friend Lizbet, who is described in very positive terms (her “gifts” are “patience, warmth, wonder,” she arrives with a “perfect and mysterious-seeming trifle” and the book she’s written is a “collection of treasures”) but is nonetheless a source of pressure in her attitude toward the narrator’s pregnancy: “It’s kind of a drag for the rest of us when people have children,” she says. The book editor, Frances, is a stressful figure for the narrator. Frances is tall, commanding, “authoritative,” and has a visibly close relationship with John, which the narrator considers “overly intimate.” The only character we have not been told about in advance is Susan, and she, we discover, is the connection to the bobcat in the title. By not describing her in advance, Lee sustains a bit longer the mystery of the title’s meaning.

The character of Susan brings tension to the story in a couple of ways. Although she is described as “peaceful,” “calm,” and “serene,” her story of being attacked by a bobcat in Nepal raises questions. First are the literal, intense questions she poses to the other guests about the meanings of bliss, fulfillment, and marriage. No one answers, but we get the narrator’s thoughts: “we were in the first minutes of meeting her, and I felt unprepared to be plunged into life’s deepest questions. . . . She was actually waiting for us to answer, to give reasons why people fall in love and get married. Nobody knows, I wanted to say. Nobody really knows. But that doesn’t mean you’re allowed to not do it.” This moment of social discomfort—Susan puts them all on the spot—raises tension with both its conversational awkwardness and with its return to the seriousness of marriage, reminding us of the narrator’s argument with her husband before the party began. Susan as a character goes on to inject drama throughout the party as the narrator comes to suspect that her bobcat-attack story might not be true.

The party goes on. The focus returns often to the Donner-Nilson affair, and to Susan’s story about the bobcat. Carefully woven throughout are small revelations about the state of the narrator’s marriage, which we increasingly realize is at the heart of this story. A little more than halfway in, we arrive at a flashback that turns out to be critical: “Our marriage was happy, I believed, though there were some puzzles in it, one of which occurred almost immediately.” She goes on to describe finding her husband inexplicably crying in a field, during their honeymoon. This “haunted our marriage a little, mostly because it was a little sad for reasons I couldn’t comprehend and felt I shouldn’t disturb.” This revelation suddenly brings a higher level of tension to the marriage question. And Lee deftly modulates again, jumping right back into the party action.

Subplots drive tension within the story. The editor, Frances, is bidding on a book proposal from Salman Rushdie and doesn’t know if she’ll get it; the lawyer narrator is awaiting the outcome of an ongoing court case. Layering several minor plot lines, each with their own level of questions and suspense, gives the story depth and texture, and the plots thematically echo each other.

Pages later, after further character and party concerns (and after, importantly, a reference to Susan’s bobcat attack as both actual incident and metaphor—the bobcat symbolizes “the fright of your life,” Susan explains), we arrive at the final scene of the story. The penultimate paragraph resolves many of the questions that have been building throughout the story, including the central tension. Someone knocks on the door and turns out to be “a plain woman . . . in a long overcoat, asking for my husband.” We are told that this woman is the reason behind her husband’s honeymoon crying, and that while the Donner-Nilson marriage will ultimately survive, the narrator’s marriage will “break apart within months.”

What’s interesting about the conclusion of this story is that while tension is relieved— many of the “what will happen?” questions are answered—Lee does not try to answer the larger questions that make up the themes of the story. This is a successful example of a closed/open ending; it satisfies the reader, who has been along for the ride and invested in these plot questions, but it allows some mysteries to remain. We don’t find out who the stranger woman is, really, nor exactly why her husband was crying on the honeymoon. And larger questions about life and marriage and happiness, echoing Susan’s awkward questions to the guests early in the story, still remain—because of course they are unanswerable. It’s a sad ending, but the last line, actually, offers a bit of relief (and ties in the title’s metaphor perfectly right at the end). Susan looks at the narrator “and her eyes let me know, Just crouch down, hold tight, there’s a little bit of pain for you, but not too much.” This “pain” . . . “but not too much” represents a final, gentle, raising and lowering of the story’s tension.