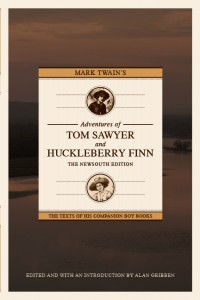

New South Books, an Alabama publisher, plans to release a version of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn wherein the n-word is replaced by the word “slave.” 219 times. The professor who originally approached the publisher with the idea did so because he himself felt uncomfortable using the word in class. I, of course, feel uncomfortable even writing it out. And if I were teaching Huck Finn, I wouldn’t utter it either, though its presence certainly wouldn’t keep me from teaching the book in the classroom and discussing this discomfort with my students.

New South Books, an Alabama publisher, plans to release a version of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn wherein the n-word is replaced by the word “slave.” 219 times. The professor who originally approached the publisher with the idea did so because he himself felt uncomfortable using the word in class. I, of course, feel uncomfortable even writing it out. And if I were teaching Huck Finn, I wouldn’t utter it either, though its presence certainly wouldn’t keep me from teaching the book in the classroom and discussing this discomfort with my students.

Needless to say, the release of this “revised” or “amended” version of Twain’s work has started quite a debate. So what follows is a round-up of some the conversations currently taking place:

Authors’ original texts should be sacrosanct intellectual property, whether a book is a classic or not. Tampering with a writer’s words underscores both editors’ extraordinary hubris and a cavalier attitude embraced by more and more people in this day of mash-ups, sampling and digital books — the attitude that all texts are fungible, that readers are entitled to alter as they please, that the very idea of authorship is old-fashioned.

Language counts here. As Twain himself said: “The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter – it’s the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning.”

[Twain] didn’t shy away from Huck’s flaws and his small-mindedness. He didn’t shy away either from his bravery and love. He didn’t make it easy for readers to unconditionally embrace that scamp; he didn’t want to. That was his genius. If a modified version of Twain can bring that brilliance to a new audience, that’s probably not the worst thing in the world. But the great satirist who created Tom Sawyer would surely appreciate the irony of finding himself subjected to such an impressive, selective whitewashing.

Racial epithets are inarguably disgusting, but not nearly so disgusting as an institution that treats human beings as property to be beaten, bought and sold. Nigger and slave are not synonyms by any stretch of the imagination. Jim’s problem is not that he is called a “nigger” but that he is chattel who can be freed or returned to his master.

It’s complicated, “nigger” is. I suffered through Huckleberry Finn in high school, with the white kids going out of their way to say “Nigger Jim” and the teacher’s tortured explanation that Twain’s “nigger” didn’t really mean nigger, or meant it ironically, or historically, or symbolically. Whatever. I could live my whole life fine if I never read that book again.

Twain the author is by no means unaware of how Huck’s use of that word increasingly misrepresents his feelings toward Jim, and so the word is intentionally loaded. “Slave” doesn’t carry the same shock value, and so it tones down what Twain is getting at.

She continues:

If students recoil — well, perhaps that is an educational opportunity, too, for both those who recoil and those who don’t. When a nation’s history is fraught with conflict, as our history is, the question always arises — can we talk with children and teenagers honestly about that conflict, or does that just generate more conflict? The brave view is that talking it out helps work it out. Maybe the realistic view is that talking it out inflames the issues further. But that is America, especially these days.

… the Congressional readers decided to omit those portions, on the grounds that they had been superseded by the 14th Amendment.

Here, contemporary sensibility won over historical text. But Kirsch notes the following when we examine this together with Huck Finn:

the two cases show the comedy of euphemism: trying to distract us from something ugly only makes the ugliness harder to miss. To the book’s new editor, the Twain scholar Alan Gribben, “slave” is less offensive than “nigger”; to the Constitution’s drafters, “all other persons” was less offensive than “slave.” By refusing to utter even that legalism, the House showed that euphemism can end only in embarrassed silence.

But then he makes the important, crucial distinction:

Unlike Twain’s novel, that classic American text was written in the expectation that it would be corrected.

| The Colbert Report | Mon – Thurs 11:30pm / 10:30c | |||

| Huckleberry Finn Censorship | ||||

|

||||