My son started telling me ghost stories before he was two years old. The most memorable was when we were out for a walk, and from his stroller, he pointed to a passing school bus.

“Mommy,” he said. “I no want to go on dat bus again.”

“Oh no? Why?” I asked, ignoring the word again. Had we ever talked about school buses before?

“I was on it.”

“On what?”

“Dat bus. Member dat?”

“No, I don’t remember. Tell me about it.”

“Dat bus tumped over. The children falled out. Member?” No, I didn’t. “Yeah. I was in it. Member dat?” I tucked a silky lock of hair behind his ear. “And dose people helped me.”

“Which people?”

“Dead people.”

Like I said, this was the most memorable story—but it wasn’t his first. He told me all sorts of things as a toddler that he shouldn’t have been able to. He named old friends and identified jobs he’d done and cities he’d lived in until it became nearly commonplace. But what does a mother do with such information? Well, if she is also a writer, after careful examination, she puts it in her pocket.

Like I said, this was the most memorable story—but it wasn’t his first. He told me all sorts of things as a toddler that he shouldn’t have been able to. He named old friends and identified jobs he’d done and cities he’d lived in until it became nearly commonplace. But what does a mother do with such information? Well, if she is also a writer, after careful examination, she puts it in her pocket.

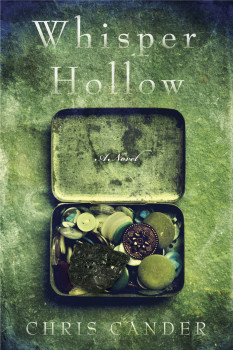

That’s how I think of my collection of ideas; my life is a long walk, and when I find something interesting—a stranger’s accent, a powerful flavor, an clip of unusual dialogue, a ghost story—I put it in my pocket the way a child might pick up a button or a penny or a nail. I hoard these ideas, amassing my collection—of what, I don’t know—until I stumble upon what will become the defining piece, that one breath-stopping artifact that demands my creative attention and brings all the other ideas together.

In the pocketful of shiny treasures that would become Whisper Hollow (Other Press), the final piece was the whisper of a woman’s voice. She leaned into me and said, “It serves me no purpose to speak for the dead.” I remember being in the car, alone, and whipping around to see the woman who was speaking from the backseat. Finding no one, my skin prickled with goose bumps. After thinking about the whispered voice all that afternoon, I sent my sister an email—I still have it—that said, “Another book idea is born.”

So I searched through my idea collection for some other interesting finds:

The devastation felt by my maternal grandmother when we moved her from the small town in West Virginia where she’d lived for ninety years

A conversation I’d had with my mother-in-law about her Polish father, who’d been a coal miner and a foreman in Nanticoke, Pennsylvania

The poem “In Memory of E. M. El-K” by Ameen Rihani, specifically the lines:

Shall I strew on thee faded blossoms. Brother,

Or fiery buds consumed by their own flame,

Or myrrh and myrtle from our Mountain-mother,

Or golden rods that whispered oft thy name?A family reunion, where I met a distant cousin who’d been brain damaged at a very young age by bacterial meningitis

A photograph by Don Davis of Odd Fellowes Cemetery in Centralia, PA that had a pried-open gap in the iron fence around it

After I decided to begin writing the book, I entered a long period of research. I queried experts on coal mining and Canon law, organ playing and watercoloring. I traveled for two days with a WVU Extension Agent and heritage tourism expert through the southern counties of West Virginia, and after a tour in which I used an antique pick axe on an abandoned seam of coal, I spent weeks emailing with an 80-year-old retired miner who helped me devise a fictional underground explosion. Over her shoulder, I watched an organist play during Catholic Mass. A Carmelite prioress told me how to get into a convent, and a Jesuit priest told me how to get out of a marriage.

And then nearly every day for several years, I sat at my desk and assembled ideas and information. Along with the owner of the whispered voice, who became Alta Pulaski, one of the three main female characters, and the eerie stories from my son, which inspired Gabriel Pollock, the unusual little boy who was the product of an incestuous rape, I added other characters to the religious immigrant communities that comprise the small coal-mining town of Verra and the adjacent Whisper Hollow. As their complicated lives unfolded, along with their passions and secrets and misdeeds and triumphs, the story slowly, finally emerged. As Henry James says, we work in the dark, we do what we can, the rest is the madness of art.

I tell you these things from the vantage of retrospection. I remember the research, the days and years spent at my desk writing, deleting, revising, editing. I rewrote the entire manuscript several times. But I can’t tell you exactly how. In addition to the madness, there’s a sort of transcendent amnesia associated with writing a book. Certain memories and impressions remain after the fact, but it’s impossible to accurately recreate the story behind the story. How did one idea beget another? At what point did I discover what the book might be about? When did the structure present itself? In fact, I’m not certain I can trust my own accounting of how Whisper Hollow came to its final form. I am a storyteller after all, and truth and memory tend to intersect in strange places.