Every book we feature on Fiction Writers Review has won the admiration of our reviewers. But because it’s a new year, and it’s award season, and today is the official holiday of love, we asked our contributors to tell us which books of 2009 they most adored, cherished, and crushed on.

Every book we feature on Fiction Writers Review has won the admiration of our reviewers. But because it’s a new year, and it’s award season, and today is the official holiday of love, we asked our contributors to tell us which books of 2009 they most adored, cherished, and crushed on.

What we received often transcended mere lists; writers shared why these certain books affected them, woke them up, even made them jealous. So in addition to the “favorites” that received the most votes, we’ve also included some of these endorsements and mini-reviews. Most selections are arranged by genre (Novel, Story Collection, etc.), and then there are less conventional categories–like Book You Loved But Would Be Embarrassed to Be Caught Reading.

Which books did you fall in love with last year? Which were delicious flings and which, life-long companions? Comment and let us know!

Novels We Loved

Sag Harbor was one of our contributors’ favorite novels. In her FWR review, Natalie Bakopoulos writes:

Sag Harbor is driven not by plot but by time, by the fleetingness of summer and its constant reminder of that fleetingness. The beginning is slow, with the sense of months ahead, time to digress and ponder and imagine and internalize, with the thickest, most dense prose socked in the middle of July, the more desperate, urgent bursts as we careen toward Labor Day. The writing is wonderfully languorous throughout, like summer itself, and a perfect match for adolescence: unrestrained and indulgent but wonderfully self-conscious as well.

When Jeremiah Chamberlin talked with Colson Whitehead at the Ann Arbor Book Festival, he asked how the process of writing this more autobiographical book compared to that of his previous novels. Whitehead responded:

When the writing slowed down it was because I was trying to figure out what I remembered from being a teenager, or what I had discovered about the time period and the community that would work in the story. In previous books I had a lot more free reign to invent stuff. Some of them take place in very fantastic stages or there’s a kind of heightened reality. So I had to figure out how to play it straight and stick to the facts and make the facts useful in the story.

Another novel at the top of our lists was Nami Mun’s debut, Miles From Nowhere, which was short listed for the Orange Prize for New Writers. Her novel-in-stories follows Joon, a runaway teen living on the streets of the Bronx in the 1980s. Mun captures both the vulnerability and the toughness of this character–to say nothing of her ingenuity–with remarkable grace and compassion. When Greg Schutz interviewed the author, she discussed the relationship between Joon’s life and her own:

Another novel at the top of our lists was Nami Mun’s debut, Miles From Nowhere, which was short listed for the Orange Prize for New Writers. Her novel-in-stories follows Joon, a runaway teen living on the streets of the Bronx in the 1980s. Mun captures both the vulnerability and the toughness of this character–to say nothing of her ingenuity–with remarkable grace and compassion. When Greg Schutz interviewed the author, she discussed the relationship between Joon’s life and her own:

Considering that I also left home for good at an early age, and that I’ve held some of the jobs Joon does in the book, I think it’s very fair for readers to wonder if the book is autobiographical. Emotionally speaking, the book definitely expresses some of the feelings I have felt in my life, but the actual scenes, dialogue, events, etc. portrayed in the book are very much fiction. To put it in numbers, 99% of Miles from Nowhere is pure fabrication. The remaining one percent represents what I think of as kernels of real life that provided the spark for that 99%.

Elizabeth Ames Staudt’s passionate recommendation of Everything Matters! by Ron Currie, Jr. (Viking) makes me want to pick up a copy:

Not since Season One of The Wire has anything fictional caused me to weep so desperately. This novel takes some risks structurally, and it kept going places that, in the hands of a lesser writer, could have been danger zones. But Ron Currie Jr. breaks the readers’ hearts in the best way a book can–by making us want to suck the marrow (and blood and muscle and vaporous stuff that must be soul) out of every last minute we have during our too-short time on earth.

Why did our contributors rave about Padgett Powell’s The Interrogative Mood? Can you really write a successful novel composed entirely of questions? Isn’t that a gimmick?

Valerie Laken, author of Dream House, says that in this case, it works. If you’d like to hear an excerpt, here’s a YouTube video of Powell reading from the book; to learn more about it, readthis “Briefly Noted” review from The New Yorker.

Laken’s own book was a standout this year, and a top pick of our Contributors. Though already an acclaimed writer of short fiction, Dream House is her first novel. She spoke with FWR’s Peggy Adler last spring about the process of moving from the short form to that of the novel, saying:

Laken’s own book was a standout this year, and a top pick of our Contributors. Though already an acclaimed writer of short fiction, Dream House is her first novel. She spoke with FWR’s Peggy Adler last spring about the process of moving from the short form to that of the novel, saying:

I agree with your comment that writing a good short story requires a very exacting degree of skill, whereas novels can have a few flaws and still be widely loved. I don’t think people expect perfection from a novel as they do from a short story. I can wince and squirm over a single line when I read a story, but in a novel, when I encounter a bum line, even a bum paragraph or chapter, I often just shrug and keep reading onward.

On the other hand, writing a novel requires so much more stamina and faith than a story. It’s a little like those people who get in their sailboats and sail to a far-off island, just for the adventure of it. I always think they’re insane, because the idea terrifies me: what if you get lost out there all on your own, and no one knows how to find you? Most of writing a novel feels like that kind of middle-of-nowhere, you’re-on-your-own sort of journey. And there are so many days when you wake up in the middle of the ocean with no wind in sight and think, “Why the hell did I sign on for this”

Few books were more eagerly anticipated this year than Lorrie Moore’s A Gate at the Stairs . And the wait was worth it for many Moore fans, myself among them. I love Lorrie Moore unconditionally, like a dumbstruck teen, and A Gate at the Stairs (her most novel-ish novel yet) reaffirms and renews that love. In this coming of age story, college student Tassie takes a part-time nanny job for a white couple on the cusp of adopting a mixed-race baby. Rather quickly, Tassie learns about the world beyond the small farm where she grew up. As she forms a loving attachment to her little charge, she’s also faced with an onslaught of big issues — from racism and terrorism to the darker sides of marriage, family, sex, loyalty–as well as life’s smaller mysteries: she uses her roommate’s dildo to stir her chocolate milk. Here is some of the finest yet of Moore’s brutal, gorgeous, pun-soaked prose that creates tension between witty satire and real human connection. This novel is not tidy or well-structured, and there is one subplot that, were I lucky enough to be her editor, I’d have urged her to abandon…but the story at this book’s center is amazing, as are its main character and voice–so the book as a whole is no less than amazing, too.

Few books were more eagerly anticipated this year than Lorrie Moore’s A Gate at the Stairs . And the wait was worth it for many Moore fans, myself among them. I love Lorrie Moore unconditionally, like a dumbstruck teen, and A Gate at the Stairs (her most novel-ish novel yet) reaffirms and renews that love. In this coming of age story, college student Tassie takes a part-time nanny job for a white couple on the cusp of adopting a mixed-race baby. Rather quickly, Tassie learns about the world beyond the small farm where she grew up. As she forms a loving attachment to her little charge, she’s also faced with an onslaught of big issues — from racism and terrorism to the darker sides of marriage, family, sex, loyalty–as well as life’s smaller mysteries: she uses her roommate’s dildo to stir her chocolate milk. Here is some of the finest yet of Moore’s brutal, gorgeous, pun-soaked prose that creates tension between witty satire and real human connection. This novel is not tidy or well-structured, and there is one subplot that, were I lucky enough to be her editor, I’d have urged her to abandon…but the story at this book’s center is amazing, as are its main character and voice–so the book as a whole is no less than amazing, too.

A debut novel worth proclaiming our love to is Sima’s Undergarments for Women, by Ilana Stanger-Ross (Overlook). Several FWR contributors (myself among them) enjoyed discussing this book last year, off-site–and here’s an excerpt from Lee Thomas’s forthcoming review:

Many reviewers of this debut novel by Ilana Stanger-Ross note the sensitivity and care she uses to describe Sima Goldner’s small basement lingerie shop: the neighborhood gossip, the constant trips up and down a stepladder, the dressing room sessions that are equal parts therapy and the quest for the perfect fit. Stanger-Ross definitely has an eye for detail, and an ear for humor in conversation. Sima and her husband Lev, both in shuffling middle age, have long since grown used to the disappointment of not being able to have children. In the Jewish neighborhood of Boro Park in Brooklyn, being childless has cast a shroud of tragedy upon them. Sima withdraws into the world of her shop. These details provide the backdrop, the story begins when a vivacious young Israeli woman, Timna, enters Sima’s shop one August day and changes everything. The book begins with the magic of Sima falling in love. Stanger-Ross conceives her lonely seamstress masterfully and completely, down to the embarrassment Sima feels when caught staring at Timna’s perfect breasts. As Sima’s obsession with Timna’s lively presence in her life grows, so does the pathos of her longing. A rekindled yearning for motherhood carries Sima through emotions akin to romantic love: fascination, passion, jealousy and revelation.

After the literary and cinematic success of What Was She Thinking? Notes on a Scandal, Zoe Heller had big shoes to fill: her own. And our contributors say she’s done so with aplomb. Concluding her June review of The Believers , Lee Thomas writes:

Among many things, The Believers is a meditation on a marriage facing the fact of mortality and the legacy of a larger-than-life man. In a book full of conflicted personalities, Audrey epitomizes a woman of such force that other characters continually underestimate her. They miscalculate her selfishness and cunning, certainly, but also her capacity to change and surprise. For Zoë Heller there are no simple villains: no one in The Believers could be mistaken for a hero, but her characters prove incredibly seductive. Along the way one becomes mesmerized by the story, enthralled by the Litvinoffs as much as these family members are with themselves.

We’d also like to give a nod to the terrific debut novel Everything Asian by Sung Woo. In his introduction to an interview with the author, Jeremiah Chamberlin writes:

Though modeled in part on the author’s own life, Everything Asian is more than just a coming-of-age tale or an immigrant narrative. It is also the portrait of a particular community and the odd intersections that take place between people who work in close proximity to one another but don’t always know each other very well. Captured with humor and generosity, the book chronicles one year in the lives of the Kim family as they adjust to a new life in the United States and interact with fellow shopkeepers at Peddlers Town.

You can read the entire interview with Sung here.

Novel We Loved (Again!) When It Came Out in Paperback

Originally published in the fall of 2008, Hannah Tinti’s The Good Thief‘s paperback edition continues to enthrall our contributors. Charlotte Boulay reviewed the book in 2008; here’s an excerpt:

Even as Tinti’s details and characters make the novel completely her own, the author also retells a classic story, that of the resourceful orphan boy; I marvel at how effortlessly, even in that somewhat glutted field, she carries it off. Reviews have compared Tinti to J.K. Rowling, and perhaps in terms of sales this is a good thing for any author, but this is not Rowling (who I also love)—Tinti’s writing is both more emotionally complex and scarier. Unlike the characters in Harry Potter books, the friends and possible authority figures who surround Ren are deeply troubled, unreliable, and needy. They are, in other words, real people. And although saints can raise boys from the dead, Ren always has the stump of his hand to remind him that violence is present.

Fans of The Good Thief, give your Valentine a great last-minute gift: a subscription to One Story, the acclaimed non-profit lit mag that Tinti co-founded and continues to edit. (For yourself, order a copy of issue #86: Celeste Ng’s wonderful story “What Passes Over.”)

Story Collections We Loved

Speaking of short stories…this collection seemed to be on everyone’s list: no book received more votes–regardless of category–than Wells Tower’s Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned. In the opening line of his review of this collection, Brian Short writes, “The first things you feel are joy and awe.” And though that opinion darkens slightly for our reviewer by book’s end, “powerful” seems an unequivocal adjective to describe this voice and these stories.

Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned is currently a finalist for the 2010 Story Prize. The other contenders for this prestigious honor were also written by debut authors: In Other Rooms, Other Wonders (Daniyal Mueenuddin, Norton) and Drift (Victoria Patterson, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). The winner will be announced on March 3.

Another all-around favorite from last year was Allison Amend’s stunning collection Things That Pass for Love. Whether mentioned in blog posts (I’m still kvelling after seeing her read last January) or cited by other authors in their interviews, this book was clearly a house favorite. When Celeste Ng spoke with the author in October, Amend described her story-writing process:

I’m almost never sure where the story is headed, and it’s not until I write the last sentence that I realize it’s the last. I would worry that if I knew where the story was going, the prose would be too serving of that purpose. I do, however, sometimes know what plot points I want to happen, or what themes I want to explore, but I never know the ending of a story.

Stories for me are born from an amalgamation of snippets of observations that finally come together in a way that’s meaningful for all of them (or not—I have a folder of stories that… frankly… suck). One story in the collection came from my application of tingly chapstick, and wondering: if I kissed someone, would they feel the tingly-ness? The scene eventually got cut from the story, but it was a point of entry. Other times I start with a sketched plot: what would happen if someone’s dog fell in love with a different owner? Who would the original owner be, and what would that mean for him/her?

Elizabeth Ames Staudt highly recommends Girl Trouble , by Holly Goddard Jones:

I’ve been anxious for more from Holly Goddard Jones’ since reading her marvelous short story “Life Expectancy” in The Kenyon Review two years ago. Girl Trouble was every bit as wonderful as I’d hoped it would be–so good, in fact, that I still haven’t read one of the stories. Sounds weird, I know, but I was one of those kids that made my Halloween candy last until Easter. Come out with another book, Ms. Goddard Jones!

Maile Meloy’s newest book of stories, Both Ways is the Only Way I Want it, was selected as one of The New York Times Book Review’s Top Ten Books of 2009. It was a favorite of ours, too. In the closing of her December review of this collection, Celeste Ng writes the following:

Amy Hempel once described a story as “when two equally appealing forces, or characters, or ideas try to occupy the same place at the same time, and they’re both right.” That definition applies perfectly to Both Ways. There are no clear lines here, no obvious right answers. Meloy’s characters are caught between two choices that are both right—or both wrong—and that’s what makes their decisions so difficult, and makes these stories so compelling. In reading them, you feel, as Meloy puts it, “both the threat of disorder and the steady, thrumming promise of having everything [you] wanted, all at once.”

For more on Maile Meloy’s work, read Joshua Bodwell’s December interview with the author.

One of my personal favorites of 2009, Delicate Edible Birds by Lauren Groff, was also a popular pick among our writers. Each of these stories condenses the depth and scope of an epic novel into fifty or fewer pages. Groff’s characters are vivid and sympathetic, her stories romantic, her plots gripping. Delicate’s most powerful tale, “L. DeBard and Aliette,” chronicles a passionate love affair between a retired professional swimmer-turned-poet and the young, wealthy teenager with polio whose father hires him to give her swimming lessons. Spanning decades, their story is both buoyed by hope and tugged down by despair; its ending feels as unexpected as it is inevitable. Another story, “Blythe,” follows the complicated friendship between two women who meet in a poetry night class. Groff captures astutely the fluctuations of that particular dynamic of fierce, feral love shared between female friends when one is a luminous (if also dangerous and severely depressed) star and the other adopts the reluctant–even resentful–role of yes-woman/caretaker. Throughout, the prose is rich but always precise. Groff never inundates readers with too many images or adds one for the sake of mere atmosphere. The tension between her characters’ sly sense of humor and the dark situations they must navigate makes them truly flesh-and-blood, able – as people must – to find joy or at least irony in seemingly joyless scenarios. And this makes their destinies matter all the more to us.

Each of these stories condenses the depth and scope of an epic novel into fifty or fewer pages. Groff’s characters are vivid and sympathetic, her stories romantic, her plots gripping. Delicate’s most powerful tale, “L. DeBard and Aliette,” chronicles a passionate love affair between a retired professional swimmer-turned-poet and the young, wealthy teenager with polio whose father hires him to give her swimming lessons. Spanning decades, their story is both buoyed by hope and tugged down by despair; its ending feels as unexpected as it is inevitable. Another story, “Blythe,” follows the complicated friendship between two women who meet in a poetry night class. Groff captures astutely the fluctuations of that particular dynamic of fierce, feral love shared between female friends when one is a luminous (if also dangerous and severely depressed) star and the other adopts the reluctant–even resentful–role of yes-woman/caretaker. Throughout, the prose is rich but always precise. Groff never inundates readers with too many images or adds one for the sake of mere atmosphere. The tension between her characters’ sly sense of humor and the dark situations they must navigate makes them truly flesh-and-blood, able – as people must – to find joy or at least irony in seemingly joyless scenarios. And this makes their destinies matter all the more to us.

Joshua Bodwell recommends 2009’s Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award winner, Love Begins in Winter by Simon Van Booy:

Stumbling upon this collection and writer was, hands down, my “big discovery” of the year. I completely lucked into hearing Simon read in New Hampshire back in late June. His work knocked me out of my chair. He was also just a completely charming guy. I bought and devoured this collection…then I re-read it to savor the lyrical prose. By October, I’d arranged to host Simon for his first trip to and reading in Maine.

Several contributors recommended Alice Munro’s newest collection, Too Much Happiness. Contributor Mary Westbrook writes:

I just finished Too Much Happiness. Maybe not her “best” work, but I do like how weird Munro has gotten. That’s not a very “literary” way to describe her work, but that’s how I feel. Her stories are wild. Though I had read several of the stories in the collection before its publication (in the New Yorker and Best Of series), I was compelled and surprised by the randomness — or seeming randomness — of violence in the collection, particularly in its first half. The gloves come off right away, so to speak. I think this collection taps into some collective anxiety lurking in the air, without sacrificing storytelling.

Even before Tunneling to the Center of the Earth hit the shelves and was an Andrew’s Book Club pick, many FWR contributors were excited to read it. The stories in this collection have appeared previously in such places as The Cincinnati Review, One Story, Ploughshares, The Greensboro Review, and Meridian. The title story and “The Choir Director Affair” were also anthologized in the 2006 and 2005 editions of New Stories of the South, respectively. And the collection did not disappoint.

Here is a preview from Brian Short’s forthcoming review, which will be published by FWR later this month:

Kevin Wilson, who also helps to run the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, has put together a strong and surprising collection of deceptively odd stories. We encounter an old woman who works as a substitute grandmother for children whose real grandmothers have died, or gone senile, or have had a falling out with the real parents. We follow a young man who, in addition to working in a Scrabble factory—trolling all day through hills of letters to find those he has been assigned—also might have a genetic predisposition to spontaneous human combustion. There is a second-person story, and another in the form a handbook or lexicon. Clearly, Wilson is interested in the formal possibilities of the short story. But unlike many authors with similar interests, Wilson never abandons the very human and often shockingly tender hearts of his stories or their characters.

Another debut collection (and Andrew’s Book Club selection) we couldn’t wait to read was What the World Will Look Like When All the Water Leaves Us. We’ve read Laura Van Den Berg’s stories in One Story, American Short Fiction, and the Baltimore Review, and her work has been anthologized in Best American Non-Required Reading 2008, Best New American Voices 2010, and The Puschcart Prize XXXIIV. Here’s an excerpt from Liana Imam’s forthcoming review of this collection:

Two books in 2009 made me cry: Lorrie Moore’s new novel and this collection. The stories here–about women who are lonely and, at times, want to be lonely, and who don’t want to live a life of drinks and goings out with people–are chasing the tails of the same legends as their characters: Bigfoot, the Loch Ness Monster, and contentment. And these stories were saddest because these characters always almost had what they wanted; they just wouldn’t reach all the way for it.

Anthologies We Loved

Each year, a bookshelf’s worth of “Best of” anthologies are published, but one of our favorites is Dzanc’s Best of the Web series. We were fans long before Christine Hartzler’s essay “Games Are Not About Monsters” was selected for inclusion in next year’s collection. Honest. Here’s what Jeremiah Chamberlin had to say about Best of the Web 2009 last August:

Each summer Dzanc Books releases The Best of the Web, an annual anthology of the year’s best poetry, fiction, and nonfiction that was published online. Of all the “Best of” collections that come out each year, this anthology, with its multi-genre interests, probably has the most in common with The Best American Non-Required Reading series. And like that anthology, this one also shares an interest in work that is driven by voice, that isn’t afraid to test the limits of its form.

Another collection that impressed our contributors was Rasskazy: New Fiction from a New Russia (Tin House, 2009), edited by Mikhail Iossel and Jeff Parker. T.M. De Vos reviewed the book for FWR:

Life in Russia, said author Aleksander Snegirev at Housing Works’ September 21 Rasskazy event, is uncomfortable, but always interesting.

So, too, are the stories in this plump new anthology: Arkady Babchenko’s beleaguered soldier returns to Chechnya a page away from German Sadulaev’s lyrical descriptions of Chechnya’s devastated countryside. The binding is a veritable trench, across which both narrators peek at each other warily.

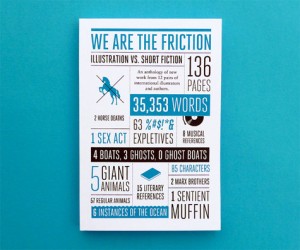

One of the most innovative anthologies last year was We Are the Friction: Illustration vs. Short Fiction, edited by Jez Burrows and Lizzy Stewart, who together form Sing Statistics. This project paired twelve illustrators with twelve short fiction writers from around the globe: each artist created a piece of work inspired by an author’s story, while each author penned fiction based on an artist’s illustration. In her review of the collection, Lee Thomas wrote:

The collection’s numerous jumping off points reminded me of the Creative Commons ethos, or collaborative innovators like Jonathan Lethem and his Promiscuous Materials project. We Are the Friction invites a third collaborator into the mix: the reader. The stories and illustrations provide a beautifully executed sketch of an idea, a mood, a relationship that leaves the reader imagining the periphery of the story, what comes before, what after. Some work better than others, but that, I suspect, is a function of individual taste and would be entirely different for another set of eyes.

The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Writing Flash Fiction , edited by Tara L. Masih, is a collection of 25 brief essays on the form, written by such authors as Robert Olen Butler, Ron Carlson, Stuart Dybek, Pamela Painter, and Jayne Anne Philips. In her FWR review, Sophie Powell writes:

As a creative writing professor at Boston College, I frequently use collections of flash fiction, stories which usually run 1,000 words or less. Given time limitations and the varying writing experience of my students, these versatile, word-limited pieces are a very approachable and satisfying form to work within. However, I always find myself floundering about when I try to explain and define this genre for the first time. As Pamelyn Casto, one of the thought-provoking, inspiring contributors, puts it: “Flash fiction is difficult if not impossible to define – and should be allowed to remain so – because this type of writing is protean… it takes on various shapes and uses different strategies to achieve its goals.” This is why this collection is so successful, and so essential, to anyone in the field of short fiction who teaches, writes, and is interested in its history and practice. These essays are probing and explorative rather than reductive and constrictive. A true ‘field guide’ in spirit, I came away thoroughly more equipped to teach and write short fiction in a richer, more illuminating way.

Mysteries We Loved

In 2009, many writers enjoyed The Girl Who Played with Fire by Stieg Larsson, the second book in the author’s Millennium triology. The third installment, The Girl Who Kicked The Hornet’s Nest, has just been released. Charlotte warns that “anyone who underestimates this mystery/thriller series does a disservice to themselves.” (Read Lee Goldberg’s review of the first book in the series, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo)

In 2009, many writers enjoyed The Girl Who Played with Fire by Stieg Larsson, the second book in the author’s Millennium triology. The third installment, The Girl Who Kicked The Hornet’s Nest, has just been released. Charlotte warns that “anyone who underestimates this mystery/thriller series does a disservice to themselves.” (Read Lee Goldberg’s review of the first book in the series, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo)

Young Adult Novels We Loved

The contributors who recommend The King of Attolia by Megan Whalen Turner urge readers to start from the beginning of this series with The Thief. Here’s an excerpt from Charlotte Boulay’s upcoming review of this YA novel:

…of all the books I’ve read in recent memory, not many compare to this series, which is serial narrative of the best kind—the kind that gets richer and more complex as it develops. There are three novels presently published: The Thief, The Queen of Attolia, and The King of Attolia. A fourth, A Conspiracy of Kings, comes out in late March. I can’t wait. […] [A]mong YA fantasy novels, The Thief is exceptional because it’s a story about adults. These are not the sudden inheritors of magical powers, but people who have carried the weight of responsibility for their entire lives. Although I love the tradition in YA novels of getting rid of the parents early on so the young protagonists can transgress and transform, it’s also refreshing to break that mold.

– In The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, what was once North America is now Panem, a dystopic society where twelve impoverished districts are forced to pay their dues to the rich capitol that quashed their rebellion, and the price is awful: every year, each district must send one girl and one boy to compete in the culmination of reality television’s horrors, the Hunger Games, where children must fight to the death until only one remains. Collins delivers an inventive, suspenseful story that raises important questions about timeless and timely issues. And I was thrilled to find that the novel’s central character, 16-year-old Katniss, is brave, strong, and clever: finally, a girl that readers of both genders will be able to identify with and admire! This book is the first in a trilogy; the second book published a few months ago, and the third is due to publish later this year.

– In The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, what was once North America is now Panem, a dystopic society where twelve impoverished districts are forced to pay their dues to the rich capitol that quashed their rebellion, and the price is awful: every year, each district must send one girl and one boy to compete in the culmination of reality television’s horrors, the Hunger Games, where children must fight to the death until only one remains. Collins delivers an inventive, suspenseful story that raises important questions about timeless and timely issues. And I was thrilled to find that the novel’s central character, 16-year-old Katniss, is brave, strong, and clever: finally, a girl that readers of both genders will be able to identify with and admire! This book is the first in a trilogy; the second book published a few months ago, and the third is due to publish later this year.

A Memoir We Loved

Helen W. Mallon recommends The Locust and the Bird by Hanan al-Shaykh:

I love the voice al Shaykh creates–though this is a first person memoir, it’s in her mother’s voice and not her own. Yet the warmth, passion, and power she evokes is intimate, like the lingering perfume of a friend who’s just left after sharing tea for the afternoon. In the prologue, Lebanese-born novelist and journalist al-Shaykh writes that her mother, Kamila, respected Hanan’s career while openly scorning its limitations. On a balcony during one of al-Shaykh’s visits home, Kamila declared: “(The politically active women you write about) were privileged. Maybe nobody encouraged them, but at least they weren’t oppressed. But what about the women who are treated as less than human because they are female?…Perhaps you are not curious to know about my childhood, and why I left you?” What daughter could tolerate hearing such a story? What daughter could resist? Al-Shaykh gave Kamila a first-person voice in The Locust and the Bird, stepping aside so that her mother, unable to read or write, “wrote this book,” revealing how she “transformed her lies into a lifetime of naked honesty.”

Poetry Collections We Loved

All-American Poem by Matthew Dickman

End of the West by Michael Dickman

The Dickman twins were 2009’s Poet Celebrities…and while the media lusted after their family resemblance, we at FWR loved how mindblowingly grand and unique (from the other) each poet’s work was.  Reading the books together is an experiment we recommend. Also? It’s kickass that we even HAVE poet celebrities in 21st century.

Reading the books together is an experiment we recommend. Also? It’s kickass that we even HAVE poet celebrities in 21st century.

It may be from 2008, but several contributors insisted that we recommend Corinna A’Maying the Apocalypse by Darcie Dennigan.

Book You Loved But Would be Embarrassed to be Caught Reading

Paperback copies of The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Society, by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows, flew off the shelves in 2009. Even writers, we snobbish creatures who blush to be reading what everyone else is, are buying — and loving — this bestselling novel, nominated by several writers for this category. One anonymous contributor writes:

Paperback copies of The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Society, by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows, flew off the shelves in 2009. Even writers, we snobbish creatures who blush to be reading what everyone else is, are buying — and loving — this bestselling novel, nominated by several writers for this category. One anonymous contributor writes:

It’s just so, so popular. Every bookclubber has read, discussed, and gifted it at this point. But with good reason. Masses, you have good taste!”

Best Book with The Worst Cover (Don’t Judge it)

Hand of Isis by Jo Graham

Most Satisfying Book for Your Inner Nerd

How I Become A Famous Novelist by Steve Hely. Read Richard Parks’s review.

How I Become A Famous Novelist by Steve Hely. Read Richard Parks’s review.

Most Satisfying Book for Your Outer Nerd

Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms by Ethan Gilsdorf. You can read Sophie Powell’s review of the book here.

What You Plan to Give Your Spouse So You Can Read It

The Selected Works of T.S. Spivet, by Reif Larsen. This inventive, beautifully illustrated novel about cartography is a Staff’s Pick at Powells.com; read why.

Book You Haven’t Read Yet But Are Dying To

Changing My Mind by Zadie Smith. Elizabeth explains why:

In “Read Better,” her 2007 essay in the Guardian, Zadie Smith writes, “I have said that when I open a book I feel the shape of another human being’s brain.” The shape of Zadie Smith’s own brain feels marvelous, as lovely and winding as the cover of her new collection, Changing My Mind, which I cannot wait to get my hands on.

More Books We’d Send Roses and Chocolates To

– The Thing Around Your Neck by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

– Await Your Reply by Dan Chaon

– The Spare Room by Helen Garner

– The Program Era by Mark McGurl (Read Mary Stewart Atwell’s interview with the author here.)

– Lowboy by John Wray

– How to Leave Hialeah by Jennine Capó Crucet

– Eating Animals by Jonathan Safran Foer

– Let the Great World Spin by Colum McCann

– Marielitos, Balseros and Other Exiles by Cecilia Rodríguez Milanés

– Beautiful Creatures by Kami Garcia and Margaret Stohl

– The Year of the Flood by Margaret Atwood

– The Magicians by Lev Grossman

Many thanks to Associate Editor Jeremiah Chamberlin for helping both to compile results and to create this feature.

And for a list of categories so awesome it needed a post of its own, check out Brian Bartels’s own Valentine to 2009’s books on the FWR blog.

And for a list of categories so awesome it needed a post of its own, check out Brian Bartels’s own Valentine to 2009’s books on the FWR blog.