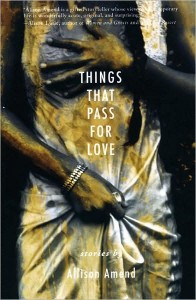

Allison Amend / photo credit: Stephanie Pommez

Allison Amend’s debut collection, Things That Pass For Love (Other Voices Books) bears not one but four blurbs commenting on the sheer variety of stories and voices within. And rightfully so. Amend peppers her stories with flecks of weirdness—a book-club attendee in love with his hostess’s dog; a pair of gay Latvian porn stars named Gregor and Ignatz; a fifteen-foot bronze statue of Ponce de León’s wife—but each is firmly rooted in the real world and real human emotions. Lovers misunderstand each other. Marriages crumble. And people reach out, again and again, searching for connection.

Amend has studied at Stanford University and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Her work has received awards from and appeared in One Story, Black Warrior Review, StoryQuarterly, Bellevue Literary Review, The Atlantic Monthly, Prairie Schooner, and Other Voices, among other publications. She has been awarded residencies at Yaddo, Djerassi, Saltonstall, Vermont Studio Center, Fundación Valparaiso (Spain), Gibraltar Point Centre for the Arts (Canada), and The Barn.

Celeste Ng interviewed Allison Amend by email as Allison began a residency at Ledig House.

CELESTE NG: I was particularly struck by the first story in your collection, “Dominion Over Every Erring Thing,” which starts with that killer opening: “I am teaching my fifth graders to add fractions when the body falls. Only one of the students looks up.” The teacher is horrified by those bodies falling from the sky, yet her students aren’t fazed at all. That’s so chilling, and for me, the tension in the story comes from that (untenable) emotional disparity. Where did the idea for this story come from? How long did it take you to put it together?

ALLISON AMEND: The idea for this story came from my work as a Teachers and Writers’ Collaborative Teaching Artist. I was sent into classrooms of children who were emotionally disturbed, and I often suffered the same verbal abuse (though, unlike Ms. Gold, it tended not to upset me quite as much—I must have a thick skin). My tour of one school consisted of: “Here’s the bathroom, here’s the principal’s office, here’s how you take down a kid who’s attacking you so that neither of you gets hurt.” My classrooms were violent, but the aggression was mostly directed at other classmates. I did once dodge a stapler. Students would cuss me out a blue streak, then cry when I left the classroom.

At the same time, I read of people who climb into airplane landing gears to stowaway. Occasionally bodies do fall from airplanes. Those two images formed a horrible parallel for me: violent children and falling bodies. I wrote the story fairly quickly, and the revision process was virtually painless. It was a good, unexpected, unusual experience.

On a related note, I love the design of my collection, but I realized too late that the story ends on the bottom of a right-hand page. It looks as though it might continue, which I think makes the ending more jarring than I intended. It made me think about form, and how form might influence the reading experience, which would be different if the reader was aware that he/she was reading the last paragraph.

Your stories are like curve balls: they careen into such unexpected places, but they don’t suddenly veer off course; they were curving there all along. And that makes me wonder about your story-writing process. When you sit down, do you often know where the story is headed, or are you usually surprised? How do stories tend to form for you?

I prefer golf imagery to baseball imagery, if you please. My stories hook or take odd bounces. I’m not a prolific writer. I think I write the story in my head before I sit down at the computer. That said, my first drafts are very messy. Please don’t publish anything of mine posthumously without serious revision. My similes are appallingly bad. Usually I start the story in the wrong place, include too many scenes, and need to cut the last paragraph, which overexplains.

I’m almost never sure where the story is headed, and it’s not until I write the last sentence that I realize it’s the last. I would worry that if I knew where the story was going, the prose would be too serving of that purpose. I do, however, sometimes know what plot points I want to happen, or what themes I want to explore, but I never know the ending of a story.

Stories for me are born from an amalgamation of snippets of observations that finally come together in a way that’s meaningful for all of them (or not—I have a folder of stories that… frankly… suck). One story in the collection came from my application of tingly chapstick, and wondering: if I kissed someone, would they feel the tingly-ness? The scene eventually got cut from the story, but it was a point of entry. Other times I start with a sketched plot: what would happen if someone’s dog fell in love with a different owner? Who would the original owner be, and what would that mean for him/her?

photo by mikebaird (flickr cc)

The characters in many of your stories are habitual, almost professional outsiders—outsiders who desperately want in. I think of the cybererotica writer-slash-book club hostess in “The People You Know Best,” who guides but does not participate in discussions and who writes erotica for people she’ll never meet. And of course there’s the cult infiltrator in “The Cult of Me,” and the homeschooled adolescent narrator in “The World Tastes Good.” What do you think draws you to this theme?

I’ve never met someone who doesn’t feel like an outsider or a pretender some of the time (nor would I like to meet such a well-adjusted person). I know I feel that way a lot of the time. I think this is a very common feeling, which lends a certain sympathy and universality to characters who may not be all that likeable, or who have situations that are unique. It also provides a motivation for the character—to try to get in—while it simultaneously gives him/her perspective on a situation that is slightly foreign.

Okay, a big philosophical question. Nearly all of your characters long for connection but ultimately fail to find it. Do you think it’s possible to for people to achieve those kinds of connections? Or do you think that for the most part, we’re doomed to live solipsistic lives?

Well, Dr. Freud, connection is what we long for most as humans, is it not? The famous E.M. Forster quote, “Only connect,” is famous for a reason. I have seen people find a significant connection, but it’s not necessarily with the person that society tells us we should be connected to in this way. Often the connections we’re supposed to have, with our spouse or our children, are the least satisfying. Instead, the connection occurs with a sibling, or a colleague, or a stranger, or a dog. I’m most interested in the connections that occur between unexpected people. I shared a laugh on the subway the other day with a total stranger when the man next to us started rocking out, singing tunelessly to Christian pop. My laughter partner and I were just checking in to see if we shared the same reality. A satisfying life can be made up of several of these connections. It’s when we start looking for a complete connection from one source that we’re doomed to disappointment. Is our hour up yet? You’ll take a check, right?

The voices in this collection are so different: an awkward father, a grad student slowly going unhinged, the first-person-plural voice of an entire town. It’s tough to throw your voice into so many different registers and to do it convincingly. What advice do you have for writers who are tackling voices very different from their own? (I guess this is a question about the “Write what you know” myth—how do you manage to write what you (presumably) don’t know and still have it ring true?)

My recommendation is don’t think too much about it. In the Road Runner cartoons, it’s not until the coyote looks down that he falls. If you worry about “authenticity” of voice, you’ll ruin what brought you to that voice in the first place. Ethan Canin, my professor at Iowa, always said, “Deeply imagine.” I took from that phrase the idea that if you put yourself in someone’s head, without judgment, what comes out of your “pen” will feel true. And then do some research to throw in a couple of convincing details and pray that no one who is an expert in that area reads the story.

In your piece for Glimmer Train, “Allison Amend Is No Dan Brown,” you mention how important order is for a collection. I think this is something a lot of writers struggle with—all the poets I know obsessively tinker with the order of their poems, but most fiction writers don’t seem to give it as much attention. What did you learn from ordering your collection? Did you ever figure out that “alchemical rule”?

Yes: If A is the number of stories and theta is the change in protagonist over time, and X is the number of stories in the collection and Y the number of pages in a given story, then let superscript n equal the point of view (1 through 3) and use this equation: Order = root theta A divided by X to the n-y. If that doesn’t work, ask my editor, Gina Frangello, because she was the one who helped me order the stories.

In all seriousness, there is of course no hard and fast rule, other than I will definitely give it more consideration in the future, as I think it made the difference between being an also-ran and a published author. Of course there are practical considerations: pair stories of different lengths, don’t bunch up the stories with similar plots or themes. Also, start with a bang and end with a bang and hide the weaker stories in the middle. Beyond that, there’s a certain forward movement to a collection even if the stories aren’t linked. Like character movement, it may be subtle, but the collection should be heading in a direction, if that makes sense. And the less linked the stories are, the more important the title becomes in tying them together.

There’s been a current trend in reviewing lately—especially with the advent of Amazon reviews and Goodreads—to talk about “likeable” characters. Some of your characters are immensely likeable, like the struggling teacher of “Dominion Over Every Erring Thing,” but some are maybe less so—like the professor in “The Janus Gate” and the narrator of “The Cult of Me.” What do you think of this idea, that the reader needs to “like” the main character?

You don’t like my characters? Personally, I need to like a main character to read a story or novel, but what I like and what you like is going to be different (which is why we all have different friends). A traditionally likeable character can be a flat character without a significant quirk or flaw, which may render him unlikeable to you. Some of the most lauded books contain characters no one in their right mind would enjoy spending time with.

However, the author has to empathize with the character. I was reading a friend’s manuscript, and his hatred of organized religion turned the character of the priest into a buffoon. I recommended to him that he make the priest a real character. Step into his brain and see what his motivation is, have sympathy for him. Of course the book subsequently won many prizes. (Coincidence? I don’t think so.) A sense of pathos is much more important than likeability to interest a reader. I like all of my characters. I think some of them make horrible decisions, or have misguided motivations, but there’s something about all of them that’s interesting to me.

You’ve commented on how long you worked on Things That Pass For Love and how hard it is to place a collection. And from all reports, the market for story collections is getting smaller and smaller. Even Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge seems to be trying to pass as a novel—the stories are linked, and it doesn’t say “Stories” anywhere on the cover. What’s your take on the future of short fiction? What can we writers do to raise short fiction’s profile?

You’ve commented on how long you worked on Things That Pass For Love and how hard it is to place a collection. And from all reports, the market for story collections is getting smaller and smaller. Even Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge seems to be trying to pass as a novel—the stories are linked, and it doesn’t say “Stories” anywhere on the cover. What’s your take on the future of short fiction? What can we writers do to raise short fiction’s profile?

If I only knew… I love short stories, but they can be hard to read because you have to meet so many new people all the time. There is more work to be done on the part of the reader, and more opportunity to put the book down. Stories get tiresome if they’re too much alike, and the reader feels jerked around if they’re too dissimilar. This may just be the nature of the beast. But short stories are still around, and still winning prizes. Hang in there, short stories!

What are a few books (or stories) that you’ve read recently and enjoyed?

I met a number of emerging writers at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference this summer, and am enjoying their work immensely. Josh Weil’s The New Valley, Irina Reyn’s What Happened to Anna K., Pauls Toutonghi’s Red Weather, and Skip Horack’s The Southern Cross are all in my to-read pile. I’m very excited about reading Laura van den Berg’s What the World Will Look Like When All the Water Leaves Us, out this fall.

What are you working on at the moment?

Right this second, I’m at Ledig House, a colony in the Hudson Valley north of New York. I’m actually working on catching up on sleep, and a freelance project. But, in a larger sense, I’m working on a novel tentatively titled The Cunning Hand. In New York, a director of drawing and prints at a venerable auction house founded by her family is mourning the death of her oldest child. She begins to explore the possibility of cloning him. Meanwhile, a frustrated Spanish artist begins a project that will be the biggest counterfeit of the new millennium.

My second book, Stations West (a novel) will be published this spring by Louisiana State University Press’s Yellow Shoe Fiction Series. An historical novel relating the lives of four generations of Jewish immigrants in Oklahoma in the mid-19th Century, it is loosely based on my own ancestors.

Further Resources

– Visit Allison’s author website.

– Read stories by Allison: “Dominion Over Every Erring Thing” (on her website) and “Bluegrass Banjo” (on The Atlantic Online’s Unbound Fiction).

– More conversations with Allison Amend: Listen to a 2008 podcast interview on the Bat Segundo Show or read One Story‘s interview with Allison about her story “Stations West,” which has evolved into her novel.

– If you’re shopping for Allison’s collection, Things That Pass For Love, remember your local independent bookstore.