These notes were originally written as a preface to my forthcoming novel, My American Unhappiness. It has been deleted from the final manuscript. The pages appear here in an exclusive essay for Fiction Writers Review. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

Author’s Note (1)

You are about to begin reading my long-awaited second novel, My American Unhappiness. It’s important for me to point out that the term long-awaited has nothing to do, technically, with the quantity, of, well, awaitment, and I only mean to say that a small handful of people, many of whom I know personally and some of whom depend on me for financial support, have been awaiting this book’s arrival for a long time. Also waiting for it: My mother, my in-laws, and a few of the good folks at Bank of America to whom I owe a great deal of money. I also have a fan, a young fan who recently graduated from Livonia Stevenson High School, my alma mater, and she is very excited to read my second book judging from the number of exclamation points in her recent e-mail. To them I say, cheers. Here it is. Thanks for waiting.

I began writing this book about two or three years ago, in a hotel room in Washington D.C., after a hard and wearying day of lobbying for an increase in federal funding for the National Endowment for the Humanities. I was then working as the executive director of the Wisconsin Humanities Council, a state affiliate of the NEH. This was in 2006, in a political environment that made me feel like lobbying for federal humanities funding was about as fruitful as lobbying to make Libya the fifty-first state.

Most of my time on Capitol Hill consisted of meeting with (and occasionally lusting after) twenty-two-year old staffers, dressed, for the first time in their lives, in professional and dapper business wear, all of whom made me feel impossibly drab, chubby, and poorly dressed. I did have a meeting that afternoon with a real live congressman, Wisconsin’s Jim Sensenbrenner, who was, in fact, the last congressman I thought I’d get any face time with at all. At that point in our nation’s history, Sensenbrenner was zealously pursuing an immigration reform bill as punitive and xenophobic as any piece of legislation recently considered in the halls of American government (now playing in Arizona). Mr. Sensenbrenner greeted me and my colleague, a librarian from Waukesha, with real warmth. “You know I don’t support you people,” he said. “But have a seat and I will tell you why.” I simply smiled and did as he said.

His reasoning, I understood, was inane. He had most of his facts wrong. He had, also, no idea, or the desire to have an idea, about the difference between the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. At that time, I happened to be a freshly-minted NEA Literature Fellow, and as much as I wanted to defend these two worthy federal endeavors, I simply nodded, and took notes, and tried my best to politely inform the congressman that a number of NEH and NEA funded initiatives actually took place in his rather wealthy fifth district. When Mapplethorpe came up, as he always did, I cowardly blamed all that on those bad kids in the arts. I was representing the sainted and patriotic humanities.

In short, I listened to the Congressman for Wisconsin’s 5th District spew forth a litany of accusations, misinterpretations, and talk-radio-perpetuated myths and sat on my proverbial hands. Sensenbrenner remained cordial throughout, but he struck me as a sort of slob, unkempt and boorish. I have heard it said that he has never held a job outside of Capitol Hill, and if he had not been born rich I doubt he would have had much of a station in this society. I wish now that I had told him he was wrong. I wish now that I had called him an over-privileged jackass. I wish now that I had asked him if a man born a millionaire can have any idea about how hard an American family must work to make ends meet, let alone a family of migrant workers. Or what it feels like to choose between making the minimum payment on his student loan and the minimum payment on a hospital bill. I had a great deal of things to say, but I said nothing. I wasn’t there for that. I was there to be likable, that horrible word. And so I held my tongue. But a writer’s tongue is never held. It merely goes dormant until the muse joins him.

I returned to my room and ordered two scotches and a steak from room service, purchased a pay-per-view movie (Little Children, with the effervescent Kate Winslet), and, after finishing said movie and composing a half-hearted but lusty poem about Kate Winslet (which inspired a Google Image Search for Kate Winslet), I began to work on this novel: My American Unhappiness.

I wrote twenty-six pages that night and I suppose I owe this unprecedented bit of productivity to Congressman Sensenbrenner. All of the phrases that went unsaid at our meeting seemed to come forth from my fingertips, blackening the white screen in front me.

Given all of these facts, what I really must say, for personal and political and legal reasons, is this: This is a work of fiction. None of the events, characters, or situations chronicled in these pages are real. Seriously: I do not want my words to be used as a chance to disparage the good people in the world of the NEH or any of my former colleagues with the state humanities councils, most of whom are a wise, decent, and extraordinarily hard-working lot. Nor does the fictional Wisconsin Congressman Quince Leatherberry, who runs into a bit of trouble in the pages that follow, represent Representative James Sensenbrenner in any way. I don’t think Mr. Sensenbrenner has been involved in anything unethical. I just hate his ideas. If I hate your ideas, I turn you into a purely fictional literary character and then I beat you up.

Author’s Note (2)

A few months after that trip to Washington D.C., I finished a draft of this novel in a borrowed space, a windowless basement underneath an old townhouse from the 1840s. This was in Mineral Point, Wisconsin, where I had recently moved with my family and where I lived for four years. The house, at least the upper floors of the house, served as a lodging facility for an arts center—Shake Rag Alley—and two of the board members of that center, upon hearing that I, a young father, was having trouble finding a quiet place to write, offered me this place.

A few months after that trip to Washington D.C., I finished a draft of this novel in a borrowed space, a windowless basement underneath an old townhouse from the 1840s. This was in Mineral Point, Wisconsin, where I had recently moved with my family and where I lived for four years. The house, at least the upper floors of the house, served as a lodging facility for an arts center—Shake Rag Alley—and two of the board members of that center, upon hearing that I, a young father, was having trouble finding a quiet place to write, offered me this place.

One weekend, I went over and vacuumed and dusted and cleaned; I found an old desk and some bookshelves and set them up facing a cinder block wall where a fireplace had once been. The next weekend I went over with my laptop and a desk lamp and tried to write. I was in that cautious phase of a new project, when a writer worries that he or she will wreck the flow of words. Any change in routine seemed precarious. Still, ultimately things worked for me. Something about the claustrophobia of a dank, antique basement seemed well suited to the sort of novel I was trying to write, and I wrote faster than I have ever written before. Within four months, I had finished a 450-page draft of a novel called My American Unhappiness.

My first attempt at a second novel was already finished, languishing in a small, green metal IKEA cabinet that looked as if it was made to house dead manuscripts, a manu-crypt, if you will. That novel failed for all the reasons second novels tend to fail, including an overwhelming desire to please the critics who liked my first novel as well as a delusional belief in the majesty of my talent. It was an ambitious novel, an attempt to merge Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons and García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude into a seamless tale of generational strife and mysticism set in southwestern Wisconsin. Everybody would like me. Easy enough, yes? Nonetheless, I had to put that novel aside. All five hundred pages of it, put down in one of those acts of artistic euthanasia that feel more like murder than mercy.

My American Unhappiness, however, was and still is a more playful novel, a dark comedy with numerous references to popular culture and American politics. A great deal of the material came from my own personal life, and thus the novel was easy to write, particularly because the main character, Zeke, was sort of an amalgamation of all of my worst tendencies and tactics. Zeke is so weird and intellectually obscure and lonely that he has increasing trouble functioning in contemporary society. He is so politically disillusioned that he becomes part of the carelessness he detests. Zeke is the guy I feared I could become if I had no wife or kids or writing to hold my life together.

After that feverish five-month writing binge, I tinkered with My American Unhappiness for a while. Zeke, however, was not the problem that I confronted as an artist. The problematic character was a minor one, a creation named Mack Fences, who is based on my dear friend, Mark Gates. Those of you in the world of publishing may recognize the name, as Mark was, for many years, a well-respected, talented, and diligent sales representative for the prestigious publishing house of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. He was also named Sales Representative of the Year in 2006 by Publisher’s Weekly magazine. He is now dead.

Mack Fences was initially a minor character, a sort of fop designed to provide a bit of levity from what was an initially dark and stormy little novel. Mack Fences chain-smoked, he drank too much, and he was intellectually fierce and witty but also a wee bit of a coward. I remember one scene in particular that I thought stood out: Mack, confronted by a rabid and renegade Homeland Security Agent, quickly buckles under the weight of federal inquiry and begins naming the names of his friends involved in “un-American activities that were cynicizing [sic] the nation.” I was quite pleased with his role in the novel, and I do admit that I secretly imagined Mark, and many of his good friends in the industry, chuckling aloud at a few of the inside jokes that peppered the manuscript.

Somewhere around the time I turned in the second draft of this novel to the woman who was once my editor and whom I thought would be my editor for a long time—this was in December of 2007—Mark Gates was diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer, which had spread to the brain.

I had long considered Mark Gates to be my best friend, although I am pretty sure there are a lot of other people who also felt the same, and so I am one of many. When Mark was healthy and energetic, he and I used to talk on the phone nearly every afternoon, usually at the end of the workday, and this small ritual was always one of the highlights of the day. Mark would air a number of grievances about political figures and sing a number of praises about Madison’s service sector employees (he has always been an outrageous tipper and loved anybody who, like him, offered up sales and service with a smile). I would report to him how many words I’d accomplished that day and he would make a good show of the admiration bit: “Wow. I don’t know how you do it.” In a world where fiction writing is seen largely to be an unproductive waste of time, devoid of the ever important TRUTH and about as economically viable as selling rotten plums, Mark’s encouragement was one of the things that kept me going. I have always been an approval-seeker (hence my skill in lobbying and fundraising) and thus, Mark’s approval became a significant part of my writing life.

I had long considered Mark Gates to be my best friend, although I am pretty sure there are a lot of other people who also felt the same, and so I am one of many. When Mark was healthy and energetic, he and I used to talk on the phone nearly every afternoon, usually at the end of the workday, and this small ritual was always one of the highlights of the day. Mark would air a number of grievances about political figures and sing a number of praises about Madison’s service sector employees (he has always been an outrageous tipper and loved anybody who, like him, offered up sales and service with a smile). I would report to him how many words I’d accomplished that day and he would make a good show of the admiration bit: “Wow. I don’t know how you do it.” In a world where fiction writing is seen largely to be an unproductive waste of time, devoid of the ever important TRUTH and about as economically viable as selling rotten plums, Mark’s encouragement was one of the things that kept me going. I have always been an approval-seeker (hence my skill in lobbying and fundraising) and thus, Mark’s approval became a significant part of my writing life.

I had trouble returning to the manuscript after Mark’s diagnosis. I went to a rather maudlin Christmas party at Mark’s house around this time (one I almost skipped, so freaked out I was by his illness, but my wife made me go).

I was one of the few people in the room who knew of his diagnosis, so I spent a good deal of my time making small talk in the kitchen and then hiding in Mark’s office and sobbing.

For instance, Les, a good-hearted and kind music-loving neighbor of Mark’s, said, “Hey, Dean, do you have the Van Morrison album St. Dominic’s Preview?”

And I would burst into tears.

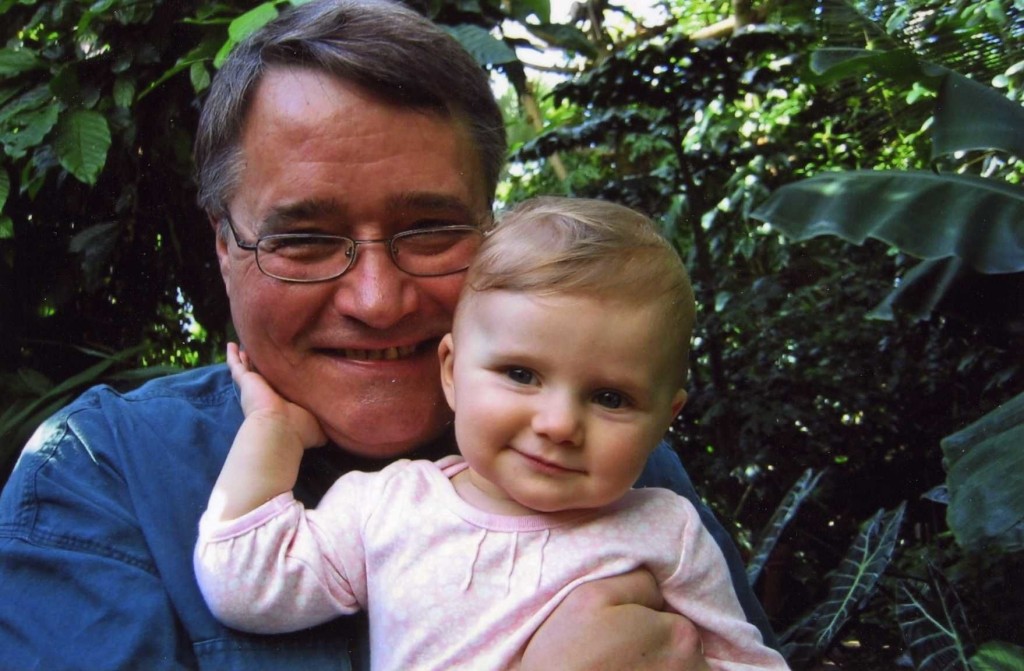

A few weeks after Christmas, there was Mark, resting in a thin blue gown at the University of Wisconsin Hospital, his head shaved and a large train track scar going along his head. I would sit with him, and his longtime partner, Stevie, and I would have absolutely nothing to say. I would either tear up and sit there, quietly weeping, or I would nod and listen and bite my lip as Stevie described the upcoming medical battery that Mark would soon have to go through. I’m sure I was a real shot in the arm. Sometimes I would bring my daughter Lydia with me. She was three at the time and was a considerable mood-lightener, despite the fact that she was a bit terrified of the hospital. I sometimes think now, in hindsight, I let her see too much of Mark’s suffering. I don’t know. Novelists make bad parents in that they often forget that suffering makes no sense to those un-obsessed with narrative.

Lydia called Mark’s IV stand his “coat rack,” and she liked to stare at the scar on his head. Often, she would draw pictures for Mark and Stevie—her godparents—and then she and I would drive back to Mineral Point, usually in the snow. It was a horrendous winter. The snow fell in record amounts, and the fifty-mile journey back to our house could often take two hours or more.

Home again, in the evenings, I would go down to my basement office in the evenings where Mack Fences, the character was still healthy and happy, a smiling postmodern Willy Loman, peddling his books with a shoeshine and a smile.

It felt odd to have the real Mark Gates sick and suffering in a hospital bed while the fake Mark Gates was going about his business. So I gave Mack Fences cancer. And then I decided that I would have him beat the cancer. I was going to use my novel to save Mark Gates’s life.

Clarification

It certainly is bad form, I suppose, to add so many introductory notes to a fiction text. Get on with it! Go! Tell your story!

I hear you.

After all, when I teach fiction writing workshops, I almost always invoke John Gardener’s dictum of the “fictive dream” and urge the writer to remain invisible in his/her own work. I am no fan of postmodern fanciness, or the sorts of “superfluous pyrotechnics” I demand my students avoid. There is narcissism in the self-reflexive act of authorial intrusion and I have spent most of my adult life pretending that I am not a narcissist. I feign interest in the lives of others. I send thank you notes. Why drop the rouse now?

But I do want to continue on this note for a moment longer: One of the problems of introducing one or two real people into a fictional world is that everybody else wants to come into the narrative too. Soon enough, the doors get thrown open. Everybody you know becomes fair game.

I tend to allow everybody into the narrative if I can find a place for them—former teachers, like Charles Baxter and Nicholas Delbanco, are alluded to in My American Unhappiness, and various nods are given to neighbors, professional acquaintances, and a motley assortment of women on whom I have had a series of marginally unhealthy crushes on over the years. I am prone to crushes, mad crushes, and if I do not write about the crushes they stay with me. They cause trouble. If I write about them, they almost immediately go away. This strategy has helped me stay married for fourteen years.

I tend to allow everybody into the narrative if I can find a place for them—former teachers, like Charles Baxter and Nicholas Delbanco, are alluded to in My American Unhappiness, and various nods are given to neighbors, professional acquaintances, and a motley assortment of women on whom I have had a series of marginally unhealthy crushes on over the years. I am prone to crushes, mad crushes, and if I do not write about the crushes they stay with me. They cause trouble. If I write about them, they almost immediately go away. This strategy has helped me stay married for fourteen years.

In a dark time, fiction begins to appear rather fruitless. A common condition after 9/11, of course, was that everything a novelist put down on the page seemed trivial in the wake of tragedy and violence on an epic scale. I remember writing a long letter to a dear friend and mentor after 9/11 saying, “Why bother?” It was a letter written about many things and by many people that autumn. I had to leave this manuscript for a few months when my best friend got cancer.

When I came back to it, my editor (who I thought would be my editor for a long time) said, with real empathy and sorrow in her voice, that I, in deference to the art of the novel, had to try to avoid sentimentality or syrupy sweetness when discussing the character of Mack Fences post–Mark Gate’s cancer diagnosis.

So I tried to do that in this novel. And I have failed in some places.

I’m aware of that. Consider this your apology.

Disclaimer

Since my daughter was born in May of 2005, there have been twenty fatal bear attacks in North America. When you consider the fact that every weekend, large numbers of largely unskilled Americans enter wilderness areas on foot, bicycle, kayak, and canoe in an orgy of panicked recreation, that’s a pretty good statistic. And when you consider that a large number of those fatal bear attacks occur in Canada and Alaska, well, then, hikers in the continental United States don’t have a huge burden of worry to carry around in their backpacks, do they?

Still, twenty people have been fatally mauled by bears.

Before I became a father, I’m not sure I would have given the statistics on fatal bear attacks much thought. I certainly wouldn’t have Googled the phrase “fatal bear attacks North America” at one in the morning the night before we were to leave on a family vacation to northern Minnesota.

But that’s what I did in August of 2008. I woke up that morning and walked down to my office—I was directing a small rural arts center at the time—and typed up my letter of resignation. I’d had a large blow-up with the board of directors the night before and this was an impulse decision. I quit, I said. Boy, did that feel good for like six minutes. And then I went home and started to pack for our vacation. Soon, thanks to the wonders of Wikipedia, and, perhaps, my refusal to go on prescription anti-anxiety medication, there was a searing pain in my chest and blurry vision blotting out the words on the screen. “WELCOME TO THE WORLD OF PANIC ATTACKS,” it should have read. “WHAT TOOK YOU SO LONG?”

~

Although I do not live in Alaska, or Montana, or any place like that, I think about bears once or twice a day. I think about the many places I might stumble upon a bear, and I also imagine unlikely encounters with bears—in parking lots or in my backyard or sitting at the diner. I have a friend who once encountered a bear—no joke—in a restroom at a national park.

Bear lovers, I’ve heard the facts: You may as well stop now. I know that bears are very rare in southern Wisconsin or central Iowa, the places I now hang my hat. And I know that the bears that would be in the Midwest are black bears, and I know that black bears are shy and fear trouble. True, I have never seen a bear in the wild. But for a long time I was convinced—in fact, I am still sort of convinced—that my end would come at the hands—at the frantic and slashing claws—of a bear.

This odd but deep belief turns most outdoor activities—hiking, camping, canoeing, taking out the trash—into a chapter of Profiles in Courage for me.

Googling anything at three in the morning, when you are unable to sleep and when there is nothing but darkness outside your office windows, is a bad idea. In fact, if you ever quit your day job with two small children at home and no Plan B, I would suggest you unplug the Internet for a few days. Avoid, at least, typing your fears into search engines: global warming, water shortage, spontaneous combustion, mild genital pain. No good can come of letting your anxious, wide-awake fingers type such phrases into a search engine. The results that come back are both horrifying and staggering.

In reality, twenty fatal bear attacks are not all that many. I have pretty good odds of dying in other, less dramatic ways in this life. But late that night, when I was supposed to be working on novel revisions, finishing them up so I wouldn’t be tempted to work during the family vacation we were about to embark on to Northern Minnesota, I googled the phrase “bear attacks northern Minnesota.”

I stayed up all night, reading stories of survival and stories of great sorrow. I read many contradictory pieces of advice on what to do in case of a bear attack. Dawn came. Amanda and the kids woke up. We’d already put a deposit down on the cabin, and my wife really, really needed a vacation, and the Ford Focus station wagon was packed up, the Thule car topper was loaded and strapped down. There was no doubt about it. I was heading into bear country. And I was bringing my wife and my two young children with me.

In the end, we survived. We did not see any bears. We even ate blueberries at the edge of a waterfall and saw no bears, though as we ate those berries at the waterfall, it occurred to me that, were I to die, dying while eating wild blueberries with your family, overlooking a waterfall in northern Minnesota, is not a bad way to go. The tooth and claw tearing your flesh and piercing your organs may not be all that ideal, but the waterfalls in that part of Minnesota are quite beautiful and the light is a certain kind of crisp white in the mid-afternoons, and my God, the berries are delicious and I love my wife and kids.

In the end, we survived. We did not see any bears. We even ate blueberries at the edge of a waterfall and saw no bears, though as we ate those berries at the waterfall, it occurred to me that, were I to die, dying while eating wild blueberries with your family, overlooking a waterfall in northern Minnesota, is not a bad way to go. The tooth and claw tearing your flesh and piercing your organs may not be all that ideal, but the waterfalls in that part of Minnesota are quite beautiful and the light is a certain kind of crisp white in the mid-afternoons, and my God, the berries are delicious and I love my wife and kids.

I tell you all of this because when I wrote my first novel, I was not a parent. This novel, my second, was attempted with children. It is a tale told by a chronically anxious, worried man whose best friend was dying.

While I don’t expect critics to bear that in mind, I would appreciate it if you, dear reader, might.

DEDICATION: This book is in memory of Mark Gates

Mark Gates was very excited to read this manuscript. He didn’t get to do that. He lived long enough, I think, to have read at least a draft of it, and it’s possible that he might have found the time and energy between bouts of chemo to at least digest all of the parts that referred to him, but I didn’t have the guts to do it. How do you show something as trivial as your own fictive musings to a dying friend?

Ultimately, I didn’t give the character of Mack Fences cancer. I took all of that out, cut countless scenes from hospital rooms and hospice care out of the novel, and made Mack Fences into the sort of character that represented the Mark Gates I wanted the world to remember.

This profession even fucks up grief. That’s what Philip Roth’s alter ego, Zuckerman, says on his way to his brother’s funeral in the novel The Counterlife, and I found that to be true. My writing career was so inextricably linked to my friendship with Mark Gates that it became harder and harder to write this novel when Mark Gates was dying, which would have been true, I think, even if the novel did not contain a character based on him. I realized that Mark had become the one person I wrote to in my head as I composed My American Unhappiness, that proverbial ideal reader (Updike’s boy in a library east of Kansas), and now he was gone.

Mark Gates introduced me to my first editor and to countless booksellers, sales reps, and publishing professionals. He was my one-man public relations and sales force, and the hardcover sales of my first novel, I’d say, are nearly all linked to his personal connections and spirit.

When I first met Mark, I was working as a bookseller, and at almost every event I went to in the publishing world, I found that if I invoked Mark’s name I could make a new friend.

“Do you know Mark Gates?” I’d ask, and always, the answer would be a delighted “I love Mark Gates!” Not “Sure, I know him.” Or “That guy from FSG/Holt?” Nope. It would always be a delighted “I love Mark Gates!”

That word love was always invoked, and although I used to tell Mark I considered it overkill (Mark and I never paid each other a compliment without a generous dose of backhanded irony), it is the only way to say it. We loved Mark Gates and we loved him because he was a man who did everything with love.

Mark loved simple pleasures—a cocktail and a good book, a perfectly prepared pork roast, talking on the phone to an old friend, an evening gathering to share stories, jokes, and gossip. He often spoke in expansive and superlative terms, even at the end of his life. He was fun to entertain because of this quality and he was everybody’s favorite dinner party guest.

I cooked for him one final time in late August of 2009, the day before I left Wisconsin for Iowa. We no longer made much of a fuss over our dinners together anymore, though once upon a time it was an occasion to wax poetic over bacon-wrapped brussel sprouts and bandaged cheddar. Mark and I could out-eat, out-talk, and out-drink everybody we knew, except for each other. Our feasts often could be described as epic.

Our last dinner together was decidedly non-epic, however. Mark had lost much of his appetite by then and he sat at the table sipping Vendage, his cheap white wine of choice, and listening to my daughter Lydia tell him about her new home in Ames, Iowa, where we were moving because I had a secured a day job again, my days as a full-time writer as numbered as a bingo card.

I defrosted some hot dogs and heated them on a charcoal grill. I warmed up a can of Bush’s baked beans and added a dash of pepper, some ketchup, and mustard. I garnished Mark’s plate with chips. He ate two hot dogs that night, and although he was exhausted and worried and uncertain he looked at me and said, “These are the best hot dogs I have ever had in my life. This is the best dinner I’ve had all summer.”

He said these things in a way that made us believe him, even if he was just being his usual gracious and grateful self. Maybe the hot dogs tasted that good to him that day. I like to think that they did. I don’t know. But I do know that his tendency to use terms like best and greatest and favorite was not an affectation: Mark Gates was at his core a truly happy man, he loved people, and he loved most everything. Every day seemed better than the last day. I’m not saying he was always cheerful or unflustered, but deep down Mark was the most content human being I have ever met.

It’s painful to know I’ll never again be at a party and overhear Mark telling some poor, unsuspecting first-time guest on the proverbial Mark Gates Show that Stevie, his partner of nearly three decades, had spent all of his “poor dead father’s money.” It’s painful to know that I’ll never feel Mark’s hand on my elbow at a crowded publishing event and hear his trademark voice deadpan, plenty loud for overhearing, “Dean, can I ask you something? When did you first realize how much you hated me?”

Most people in the small world that is publishing have our Mark moments, our phrases, and our gestures that we will never forget. His scratchy, sudden laughter. His old-school suspenders. His itchy eye, which he tended to rub with his middle finger whenever anybody teased him. When the best people go, they leave us with so much material.

The last time I saw Mark, he was incredibly weak, small, too tired even to smile. I sat at the edge of his bed and I tried to tell him all of these things, how much he had meant to me and how he taught me about what was important. I met Mark when I was just twenty-two, figuring out what was important in the world and what wasn’t, and his influence on me was profound.

“Because of you,” I sobbed, a torrent of emotion emerged. “I know that nobody important really cares what you’ve done or how much you make or what sort of house you have or what kind of car you drive. I know that friends matter more than fame. I know that…”

I broke down into more tears.

Mark slowly lifted his head and raised his hand toward me.

“I was wrong,” he wheezed. “That stuff is the most important stuff. That’s how everybody gets to JUDGE you.”

I started to laugh, held onto his hand.

“Forget everything I taught you,” he said.

I went downstairs, sobbing and laughing all the way down the stairs and out the door to my car.

When I went out on my first book tour five years ago, Mark was a nervous wreck. He had jumped through innumerable hoops to help me get published, to help me get a warm reception from booksellers across the Midwest. It was a terribly giddy moment for us, as if some dastardly plan had miraculously come to fruition.

“Don’t screw this up,” Mark told me when I called him from the Madison airport before departure. “This will reflect poorly on me if it goes badly. And on poor, poor Amanda. I just worry about her after, you know, you sully your reputation all over the country.”

“I’ll be fine,” I said, feeling the butterflies calm down in my gut.

Talking to Mark always reassured and settled me; his fixation on comical alternate realities always made the more immediate reality less daunting. It’s why I called him four or five times a day. It’s also, I suppose, why I wrote My American Unhappiness, creating a character that preferred the impulsive to the well-considered and the delusional to the certain. I can see now why I needed to spend much of the past five years with a wholly fictional alter ego: it allowed me to exist in a comical alternate reality, where tragedy and unhappiness were intellectual diversions, not real life, not the brass tacks sitting, points up, on my chair.

“And whatever you do,” Mark said to me back then, “Don’t read more than fifteen minutes.”

“Fifteen minutes?” I said. “That’s all?”

“Yes,” he said. “You always have to leave them wanting more.”

Author’s Note (3)

With those words in mind, the author decides to cut the twenty-one manuscript pages of front matter from his novel. The novel comes out tomorrow. Mark Gates never got to read it. And because of that the book will always feel, to the author, to be something short of complete.

Mark Gates with Lydia Bakopoulos, 2006

Further Links and Resources:

- Learn more about Dean Bakopoulos at his author website.

- Watch the videos for My American Unhappiness.