Editor’s Note:

Editor’s Note:

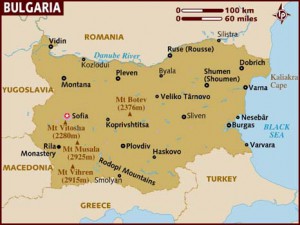

Each spring the Elizabeth Kostova Foundation selects five English speaking writers and five Bulgarian writers to participate in the Sozopol Fiction Seminar, which takes places in the tiny, historic town of Sozopol, Bulgaria, on the Black Sea. In 2009 I was lucky enough to be chosen as one of the fellows, along with then soon-to-be FWR contributor Steven Wingate. That journey was chronicled in an essay entitled “Literary Life on the Black Sea,” which FWR published later that summer.

Keeping with what we hope will become a tradition, we asked several of this year’s English speaking fellows if they would be willing to compile a similar essay reflecting on their trip to Bulgaria to participate in the 2010 seminar. Those individuals are Kelly Luce, Carin Clevidence, Charles Conley, and Paul Vidich. The results of their collaborative work is below. We hope you enjoy!

PART I: The Road to Much Excess

by Kelly Luce

Work schedule cleared, bags packed. Workshop pieces read, re-read, and noted upon. It was the end of May and time to head to Bulgaria for the Sozopol Fiction Seminars, organized by the Elizabeth Kostova Foundation. I was one of five writers working in English who’d been chosen as a fellow for this year’s event. I was ready.

Work schedule cleared, bags packed. Workshop pieces read, re-read, and noted upon. It was the end of May and time to head to Bulgaria for the Sozopol Fiction Seminars, organized by the Elizabeth Kostova Foundation. I was one of five writers working in English who’d been chosen as a fellow for this year’s event. I was ready.

But my plane was not.

The gate area grew crowded, the desk-line long. Backpacking college kids and men in suits parked on the floor near electrical outlets. Eventually, I hit the bar, where a limping Spaniard leaned over me and ordered a margarita—“a triple,” he said, “or if possible…a fourple.” As the delays extended and misinformation piled up, I calmed myself with the promise that, no matter what, I’d still catch the chartered bus from Sofia to Sozopol. It was a seven-hour ride, after all, and my guidebook warned transportation and infrastructure outside the capital was iffy at best. I was about to spend the week sharing stories and talking shop in a fascinatingly foreign, mysterious place with some of Bulgaria’s best-known writers and translators, not to mention a group of intimidatingly talented co-fellows, editors, and publishers from the U.S. and Europe. I couldn’t miss the bonding among participants that would surely occur on the long, scenic ride. (On a comfortable, air-conditioned bus, no less.)

Thirty-five hours after I’d arrived at the airport in San Francisco, I stepped off the plane onto the tarmac in Sofia, sleep-deprived and crabby as hell. I knew I’d missed the bus. But I was in good hands—Founder Elizabeth Kostova and Director Milena Deleva had made sure I wasn’t stranded. The last time I’d been able to check email, at the Munich airport hotel at three in the morning, there’d been a message from Milena: here’s the bus schedule, but we think someone will be there—maybe Simona, the program assistant?

Thirty-five hours after I’d arrived at the airport in San Francisco, I stepped off the plane onto the tarmac in Sofia, sleep-deprived and crabby as hell. I knew I’d missed the bus. But I was in good hands—Founder Elizabeth Kostova and Director Milena Deleva had made sure I wasn’t stranded. The last time I’d been able to check email, at the Munich airport hotel at three in the morning, there’d been a message from Milena: here’s the bus schedule, but we think someone will be there—maybe Simona, the program assistant?

A loud, open-air bus carried me to the terminal. It was early morning and the sun peaked from behind a distant mountain. The air was damp. Dragging my carry-on through the Sofia Airport terminal, I pondered sleepily whether it was the color or the font that made the signage look so outdated, and whether Happy Bar and Grill delivered on its emotional promise.

Near the exit, I recognized Bulgarian writer and seminar fellow Krassimir Damianov. In person, he bore the same unconcerned, slightly pissed-off expression as he did in his photo on the seminar website. Krassie grabbed my suitcase and began to talk. He didn’t stop until we reached Sozopol—over eight hours later. I couldn’t tell if he liked me or not, if this errand of transporting the helpless American was anything but a hassle. So much for making a good first impression, for earning my keep as a fellow and contributor at this prestigious seminar run by such hard-working and generous people.

In his 1972 Citroen pickup, we zoomed past child-driven donkey carts, sunflower fields, crumbling factories and everywhere, that intoxicating mix of red poppies and lavender, their rich hues somehow brightened by the tiny white blossoms sprinkled among them. Perhaps because of the guidebook’s warnings, I hadn’t expected such beauty from the Bulgarian roadside.

Krassie spoke English with a thick accent and an endearing disregard for accuracy. He called pigs “porks” and pointed out the abandoned “mineries” where stone was dug during Communism. He talked on as we headed east across Bulgaria toward the Black Sea, hardly looking at the road, the Citroen shaking as we overtook sports cars in the face of oncoming semis. “I used to be taxi driver in Sofia,” he told me. “It’s no good to drive alone. I can talk all day.” I asked questions, tried to keep up my end of the conversation, but eventually I closed my eyes. I was irritable and afraid I’d take out my frustrations on my ‘taxi driver,’ whose accent had grown incomprehensible to me in my exhaustion.

I dozed, a little. Krassie noticed me nodding off and waved a hand. “Sleep, sleep,” he said. “I will guard your dreams.” Krassie’s gentleness, the nap and the continuing understated beauty of the countryside worked their charms on me. By the time we arrived in Sozopol that night, having missed the welcome ceremony, Krassie felt like a dear relative. I made two notes in my journal upon arriving in Sozopol: There’s a bond that forms over being late to something. And, You don’t have to understand a person’s words to hear them.

The latter proved true throughout the week. During her lecture, held in the cliff-side Art Gallery building that always smelled of the sea, Kristin Dimitrova read her poem “Beliefs” in her native tongue: “…Among sailors, I suppose / there is a belief that when they shave / in an odd direction, an academic dies. / And they try not to shave. / The point is that we think / about each other.” The sound of the poem in Bulgarian had a raw, rhythmic power that transcended literal meaning and gave me goose bumps. Behind her, the huge gallery windows framed the Black Sea, cerulean under a cloudless sky. A few boats dotted the horizon. Perhaps filled with bearded sailors, I thought.

The latter proved true throughout the week. During her lecture, held in the cliff-side Art Gallery building that always smelled of the sea, Kristin Dimitrova read her poem “Beliefs” in her native tongue: “…Among sailors, I suppose / there is a belief that when they shave / in an odd direction, an academic dies. / And they try not to shave. / The point is that we think / about each other.” The sound of the poem in Bulgarian had a raw, rhythmic power that transcended literal meaning and gave me goose bumps. Behind her, the huge gallery windows framed the Black Sea, cerulean under a cloudless sky. A few boats dotted the horizon. Perhaps filled with bearded sailors, I thought.

We spent a lot of time in that airy, two-story building, its large rooms empty of anything other than a couple tables, stacking chairs, and the trove of paintings lining the walls. Daily writing workshops were held there, as were readings and lectures like Kristin’s, along with three panels on translation. The theme of translation resonated throughout the seminar, far beyond these daily panels. Over delicious, oft-photographed meals and well-crafted, velvety local red wine, the topic of language surfaced time and again. These playful, often hilarious arguments over which language was most pleasant to the ear, which was best suited for singing, which induced suffering in its speakers, which had the best euphemisms for bodily functions, were some of the most pleasant of the seminar.

Before we arrived in Sozopol, each fellow submitted work to be translated—English into Bulgarian and vice versa. Our last night in Sozopol, a reading was held in which the Bulgarian and English fellows paired up and presented the translations of each other’s work.

Krassie and I were reading partners. He chose to read the last scene of his story, “Downstream.” We met in the Art Gallery to prepare, and I read for him the opening of his piece. He shook his head. “You must read it slow, and flowing, like a river. DA, da-da-da DA, da-da-DA. Think about a current. Flowing, flowing!” He banged on the table to illustrate his point, then began to read, in his thick accent, with the gentlest rise-and-fall cadence. I immediately saw what he meant.

Krassie and I were reading partners. He chose to read the last scene of his story, “Downstream.” We met in the Art Gallery to prepare, and I read for him the opening of his piece. He shook his head. “You must read it slow, and flowing, like a river. DA, da-da-da DA, da-da-DA. Think about a current. Flowing, flowing!” He banged on the table to illustrate his point, then began to read, in his thick accent, with the gentlest rise-and-fall cadence. I immediately saw what he meant.

My writing had never been translated before. So the night before our reading when Milen Ruskov, who translated my piece, approached me to recommend I read a certain section, I was surprised. And frankly, touched. Usually, people don’t care what you share at a reading—you’re lucky if they listen. It seemed odd for someone to care about work that wasn’t his. But I realized the Bulgarian version of my story was his. Translation is not simple conversion; it’s an act of creation. During the week’s first translation panel, Svletozar Zhelev, a Bulgarian publisher, had shared his water-in-a-bottle metaphor for translation: in a successful translation, the water, or essence of the writing, remains unchanged; a translator’s job is to create a new vessel to contain the liquid. This metaphor became a seminar favorite, touching on both the physical act—alchemy, really—of changing words, and the spiritual act of engaging with another’s conscious and unconscious mind.

The night of the reading, forty people gathered on the top floor of the art gallery. The sun had set over Sozopol and the charged breeze of a hot summer night swirled through the room. Men replaced (or at least covered up) T-shirts with sport coats. I blow-dried my hair, donned a dress, and swiped on some mascara.

The night of the reading, forty people gathered on the top floor of the art gallery. The sun had set over Sozopol and the charged breeze of a hot summer night swirled through the room. Men replaced (or at least covered up) T-shirts with sport coats. I blow-dried my hair, donned a dress, and swiped on some mascara.

Each pair read to a silent, rapt audience. I introduced Krassie as my taxi driver; he compared me to his daughter, who’s the same age. The rhythm he’d pounded on the table earlier in the day entered my voice as I began to read “Downstream,” swaying as I went. And when Krassie read my story in Bulgarian, he was so expressive I was able to follow along with my English version.

Five days later—during which time the conversation and the late nights had hardly afforded me the opportunity to catch up on sleep—it was time to depart Sozopol. My taxi driver, friend, and fellow reader went to visit his new granddaughter in a nearby town, so he did not join us for the last day of the program back in Sofia. But I wished him and his Citroen well, and part of me wished we were voyaging back together. He told me to visit the hostel he runs in Barcelona. Then he hugged me, grabbed my shoulders and said, “ I wish you much excess.”

It was an appropriate slip of the tongue. If Sozopol and Sofia were marked by anything, it was excess: more ideas, inspiration, laughter, and growth as a writer and human than I could have imagined possible in those six days. And for a friend, can there be a better wish?

Part II: The Terrace of the Hotel Diamanti

By Carin Clevidence

Here’s the terrace of the Hotel Diamanti, with Elizabeth Kostova and Josip Novakovich talking at one of the tables. Warm and gracious, Elizabeth has set the tone for the seminar from our first night in Sofia; this beautiful terrace feels like an extension of her vision. At breakfast, hung-over and increasingly sleep-deprived, we sit on the cushioned chairs under the white-canvas awning to drink coffee and eat sliced cucumber and wedges of salty Bulgarian cheese. The terrace overlooks the Black Sea and red poppies bloom along the edge of the rocky cliff. Blue fishing boats pass. Gulls fly overhead. Offshore lie two islands, a large one with greenery and a lighthouse, and a smaller one, rocky and bare. My roommate Zdravka Evtimova, a Bulgarian who writes in English, tells me she swam to it once on a family vacation many years before, and that the island is infested with snakes. Nikolaj Bojkov, Bulgarian writer and translator from the Hungarian, says through our interpreter Boris Deliradev that the snakes eat fish. How do they catch them, we wonder out loud? Are they aquatic? Someone mimes a snake with a fishing rod and Niki laughs. He is wearing a tee shirt illustrated with one of the Kama Sutra’s less popular positions: “Three-Legged Lemur Juggling,” it might be called, or “Double-Jointed Monkey in the Shrubbery.”

Here’s the terrace of the Hotel Diamanti, with Elizabeth Kostova and Josip Novakovich talking at one of the tables. Warm and gracious, Elizabeth has set the tone for the seminar from our first night in Sofia; this beautiful terrace feels like an extension of her vision. At breakfast, hung-over and increasingly sleep-deprived, we sit on the cushioned chairs under the white-canvas awning to drink coffee and eat sliced cucumber and wedges of salty Bulgarian cheese. The terrace overlooks the Black Sea and red poppies bloom along the edge of the rocky cliff. Blue fishing boats pass. Gulls fly overhead. Offshore lie two islands, a large one with greenery and a lighthouse, and a smaller one, rocky and bare. My roommate Zdravka Evtimova, a Bulgarian who writes in English, tells me she swam to it once on a family vacation many years before, and that the island is infested with snakes. Nikolaj Bojkov, Bulgarian writer and translator from the Hungarian, says through our interpreter Boris Deliradev that the snakes eat fish. How do they catch them, we wonder out loud? Are they aquatic? Someone mimes a snake with a fishing rod and Niki laughs. He is wearing a tee shirt illustrated with one of the Kama Sutra’s less popular positions: “Three-Legged Lemur Juggling,” it might be called, or “Double-Jointed Monkey in the Shrubbery.”

After morning workshop we return to the terrace for grilled eggplant, shopka salata, chilled cucumber soup. The dessert is something called “yogurt ice cream.” Like frozen yogurt, I expect. But no: It comes in a little clay pot, topped with walnuts and honey and it resembles frozen yogurt like a crusty Parisian baguette resembles Wonder Bread. Kelly, Chad Post and I stare at each other, astonished that anything could taste this good. On the terrace the talk is constant, a tumult of English and Bulgarian punctuated with bursts of laughter. Even with our mouths full of honey-laced yogurt ice cream, we can’t shut up. We talk about our morning’s workshop, about the books we’re reading and the ones we’d like to read, and the books we want to write and how we want to write them.

The best food is at the Diamanti, but we eat at other restaurants as well, descending like a large flock of hungry, polyglot birds. At one the fish is garnished with apple, inexplicably fried. At another the mussels arrive already shucked, fleshy and glistening in a white bowl, and as we eat them the poet Kristin Dimitrova recites John Donne for us in Bulgarian. But after dinner we end up back on the Diamanti terrace, drinking more red Bulgarian wine, and talk about the afternoon’s translation panel, and our extraordinary writing session with Alex Miller, and later, more riotously, the Dutch space program and the mechanical bull from our failed karoake excursion of the night before. Ivan Dimitrov and Charlie are smoking. Niki takes out a handful of colored pencils and draws us each a picture; mine is a smiling snail with a house on its back, a curl of smoke rising from the chimney. The conversation surges on, fevered and digressive. “Five years ago,” one of the Bulgarians is saying, “there was an upsurge in nostalgia.” From another table, “But if it sucks on the poetic syntactic level…”

The best food is at the Diamanti, but we eat at other restaurants as well, descending like a large flock of hungry, polyglot birds. At one the fish is garnished with apple, inexplicably fried. At another the mussels arrive already shucked, fleshy and glistening in a white bowl, and as we eat them the poet Kristin Dimitrova recites John Donne for us in Bulgarian. But after dinner we end up back on the Diamanti terrace, drinking more red Bulgarian wine, and talk about the afternoon’s translation panel, and our extraordinary writing session with Alex Miller, and later, more riotously, the Dutch space program and the mechanical bull from our failed karoake excursion of the night before. Ivan Dimitrov and Charlie are smoking. Niki takes out a handful of colored pencils and draws us each a picture; mine is a smiling snail with a house on its back, a curl of smoke rising from the chimney. The conversation surges on, fevered and digressive. “Five years ago,” one of the Bulgarians is saying, “there was an upsurge in nostalgia.” From another table, “But if it sucks on the poetic syntactic level…”

One of the established writers, a seminar connoisseur who instigated the previous night’s skinny dipping, sits back in his chair and looks around the terrace with feigned amazement. “It’s great that people are so excited about ideas here,” he confides. “Usually, they just like to get banged.”

It’s after one in the morning, and I’ve been up since before six, when the gulls woke me from the red-tiled roofs crying “Ow! Ow! Ow!” like someone with a badly stubbed toe. I don’t ever want to leave the Diamanti terrace, but my eyes are beginning to close and eventually I walk across the street to the hotel. From the skylight in my top floor room I look out on the moon, shining over the dark houses of Sozopol, and the distant glittering stars. Zdravka is already asleep. A lively babble of Bulgarian and English rises from the terrace, and that’s the sound I fall asleep to.

Part III: Why We Write

by Paul Vidich

I looked out the bus window and saw Sozopol recede along the coast, its red-tiled roofs spread across the dry seaside. Had it only been four days? It seemed like weeks. My mind was a flip book of images. I settled into the bus ride beside my wife, Linda, and listened to the animated conversations happening around me. Alex Miller, in our final workshop, had presented the combined group of American and Bulgarian writers with a surprise exercise. He asked each of us to say why we wrote. I have several shallow answers that I give, and in my mind I ticked off the ones most appropriate for this group of new friends, all still basically strangers. Alex cautioned that glib answers were just that, transparent cover ups, and honest answers were difficult, but we were writers after all, and we had an obligation to tell the truth, whatever that was. “Hmmm,” I thought.

I looked out the bus window and saw Sozopol recede along the coast, its red-tiled roofs spread across the dry seaside. Had it only been four days? It seemed like weeks. My mind was a flip book of images. I settled into the bus ride beside my wife, Linda, and listened to the animated conversations happening around me. Alex Miller, in our final workshop, had presented the combined group of American and Bulgarian writers with a surprise exercise. He asked each of us to say why we wrote. I have several shallow answers that I give, and in my mind I ticked off the ones most appropriate for this group of new friends, all still basically strangers. Alex cautioned that glib answers were just that, transparent cover ups, and honest answers were difficult, but we were writers after all, and we had an obligation to tell the truth, whatever that was. “Hmmm,” I thought.

Alex called on Kelly first. I felt sorry for her. Such an important question and so little time to prepare. I had time to find words that were honest and clever. How honest did I want to get?

I had it all figured out when Alex turned to me. In that instant my comfortable mask fell and I spoke from a vulnerable place. Emotion welled in me, startling me, and I was unrehearsed. I struggled to stay articulate while weeping about my parents’ divorce when I was a child. It didn’t matter that the facts in question were forty years past. When I finished, the mood in the room had changed. I watched with interest as the next up, our Bulgarian colleagues, all men, all accustomed to protective cloaks, opened up one by one. One Bulgarian talked about a son who had recently died. Everyone was quite and attentive. This is what I thought about on the seven-hour bus ride to Sofia. And I thought how odd it was to travel five thousand miles to a remote part of the former Roman Empire to discover something about myself.

I had it all figured out when Alex turned to me. In that instant my comfortable mask fell and I spoke from a vulnerable place. Emotion welled in me, startling me, and I was unrehearsed. I struggled to stay articulate while weeping about my parents’ divorce when I was a child. It didn’t matter that the facts in question were forty years past. When I finished, the mood in the room had changed. I watched with interest as the next up, our Bulgarian colleagues, all men, all accustomed to protective cloaks, opened up one by one. One Bulgarian talked about a son who had recently died. Everyone was quite and attentive. This is what I thought about on the seven-hour bus ride to Sofia. And I thought how odd it was to travel five thousand miles to a remote part of the former Roman Empire to discover something about myself.

The bus arrived in Sofia late afternoon, and as the highway ended we found ourselves in old narrow city streets jammed with rush hour traffic. The next day, May 30, was the final portion of the Conference’s formal proceedings, a day of literary discussions co-sponsored by the American Embassy and Sofia University. On arrival at the Diamanti Hotel, Nikolaj Bojkov, a Bulgarian Fellow, had invited us to Made In Home, a restaurant located at Shandor Petofi 37, owned by Silvia and Rudi, who host a monthly literary gathering. Six of us sat around the restaurant’s single large wood table and dipped warm bread into a thick soap, a savory concoction of zucchini, onion, dill, red pepper powder, sour cream, with salt to taste, all served family style from a large clay pot. I was in a good mood. We talked, took pictures we promised to share when we got back to the States, and we carried on a lively conversation in broken English with several Bulgarian writers.

The conference ended the next evening, June 1, with readings of Fellows’ work at the Red House, 15 Liuben Karavelov Street, a four story red brick building in the city center built by the famous Bulgarian sculptor, Andrey Nikolov. The building’s style is Mediterranean, which is quite unusual for Sofia. Nikolov built the house after he returned from Rome, where he lived from 1914 to 1927. Today, the Red House is a cultural landmark. The last evening of the Conference’s events began at 7:15 pm sharp with a literary flash mob just outside the steps of the Red House. I was reluctant to participate in an event described with the opposing sensibilities of mob and literary and flash, but I was curious too. Who wouldn’t be? I showed up outside the Red House and joined other writers, conference participants, students, and passers-by. At the precise moment this ‘mob’ started reading out loud. Different work. Our own work. The work of dead poets. Anything. This created a noisy cacophony of literary gobbledygook. Words overlapped and intersected and individual words lost meaning. It ended at precisely 7:20 pm, as suddenly as it began, and just as spontaneously. Each reader dropped his manuscript in a trash basket and we dispersed on the sidewalk.

That evening’s main event was a public reading by conference fellows in the Red House’s second floor gallery. Each of the ten fellows read a brief excerpt of his or her work, and the mixed language audience read the English translation of the spoken Bulgarian text on a large projected screen (or the Bulgarian translation in the case of an English text). I introduced each of my American colleagues and Ivan Dimitrov did the same for the Bulgarian fellows. The presentation format was clever, mixing languages, diverse voices, and literary styles. The Bulgarian excerpts often gravitated toward the absurd – the employer who places a classified ad for a worker willing to be fired. We Americans wrote about varieties of emotion: love, courage, tolerance. This reinforced a running joke at the conference: Americans wrote about divorce and suicide; Bulgarians wrote about waking up a cockroach.

My evening ended on the roof of the Red House under a warm night sky among fellow writers whose company made me feel less alone in the world. I had been vulnerable and felt stronger for it. Wine and appetizers were served on a terrace that looked onto the quiet tree-lined street and Soviet-era apartment buildings. The night was cool, the food savory, and conversations took up memories of the remarkable week we’d spent together, exchanging addresses, hugs, and promises–real promises–to stay in touch.

My evening ended on the roof of the Red House under a warm night sky among fellow writers whose company made me feel less alone in the world. I had been vulnerable and felt stronger for it. Wine and appetizers were served on a terrace that looked onto the quiet tree-lined street and Soviet-era apartment buildings. The night was cool, the food savory, and conversations took up memories of the remarkable week we’d spent together, exchanging addresses, hugs, and promises–real promises–to stay in touch.

Part IV: Caesura

by Charles Conley

If I were going to try to make you feel the sense of excitement I felt at this year’s Sozopol Fiction Seminar, here’s how I’d do it. I’d write about exhaustion from jet lag and hangovers, what seemed to be unending conversation, the intoxication and surprise of making new friends, the feeling of literary discovery that was permitted mostly by my embarrassing ignorance of contemporary non-English literature. I’d also write about the blue skies, the Black Sea, and the red-tiled roofs of Sozopol; describe how befuddling it is not to know how to even pronounce a word because it’s written with a different alphabet; and, of course, proclaim to the world once again the justly famous Bulgarian sense of hospitality.

If I were going to try to make you feel the sense of excitement I felt at this year’s Sozopol Fiction Seminar, here’s how I’d do it. I’d write about exhaustion from jet lag and hangovers, what seemed to be unending conversation, the intoxication and surprise of making new friends, the feeling of literary discovery that was permitted mostly by my embarrassing ignorance of contemporary non-English literature. I’d also write about the blue skies, the Black Sea, and the red-tiled roofs of Sozopol; describe how befuddling it is not to know how to even pronounce a word because it’s written with a different alphabet; and, of course, proclaim to the world once again the justly famous Bulgarian sense of hospitality.

That’s not what I’m not going to do, though. What I’m going to do is write about the dolphins.

Friday, May 28, was our first full day in Sozopol. From 9:00 am until 7:30 pm, when dinner started, we shuttled from workshop to lunch to panel to reading. It felt as if every moment I had somewhere to be. Actually, it felt as if every moment there were two places I wanted to be—at that panel but having this conversation; listening to Elizabeth Kostova read but swimming in the Black Sea. (I had been talking about swimming in the Black Sea for weeks before the trip to Bulgaria, and I almost didn’t do it, because swimming in the Black Sea meant possibly missing something else, and that something else might have been too dear to miss.)

After lunch, right before the “Translation in Practice” panel was about to begin, as we gathered behind the art gallery that housed the workshops, panels, and readings, we saw three or four dolphins playing out in the bay. At first, I wasn’t sure—was that a splash or a whitecap? A fin or the sun and water playing tricks? Then, yes! A dolphin leaping in the water. Then another. Then a couple playing together. It was a moment when we all took a deep breath in the middle of the riot of conversation and literature and sun and food. Sometimes a moment of silence lets you hear the music within the noise. For me, this was that silence, and it changed how I heard everything that came around it. Plus, who doesn’t want to look at dolphins?

Then it was time to go inside and get on with it. There was inspiration and information inside the gallery, and after the translation panel was a reading, and after the reading was more good Bulgarian food and better Bulgarian wine, and plenty of evening stretching ahead of us.

Then it was time to go inside and get on with it. There was inspiration and information inside the gallery, and after the translation panel was a reading, and after the reading was more good Bulgarian food and better Bulgarian wine, and plenty of evening stretching ahead of us.

Then there was Saturday, with more workshopping in the morning, and more conversation over lunch, and more panels and readings after lunch—but between 1:30 pm, when lunch ended, and 4:00 pm, when the second day’s translation panel started, the schedule was clear.

This was a miracle, and though bed called—jet lag was still plaguing us and we’d all been up late the night before—several of us decided to take a boat ride out of Sozopol Harbor. Alex and Stephanie Miller had recommended the forty-minute tour they’d taken the previous day. They told us to just find the blue and white boat.

The Sozopol portion of the seminar takes place over three densely packed days, and this boat ride came in the center of that line, a forty-minute caesura when we did nothing but look at the Black Sea, calm except for the occasional wake from a passing boat, and watch buildings on the shore slide past—hotels mostly free of guests so early in the season, square and modern vacation homes, restaurants with outdoor terraces, and the art gallery, windows and cream topped by red tile, presenting its proudest side to the sea. We chatted, of course, but not the heavy conversational lifting of dinner—those dinner conversations called for wine or rakia to fuel them. We saw a mussel farm and an island that may or may not have been populated by fishing snakes, and, for a little while, it didn’t matter that we were going back to literary conversation and activity of the most intense sort, because we were out on the sea in a small boat and everything around us was beautiful and new.

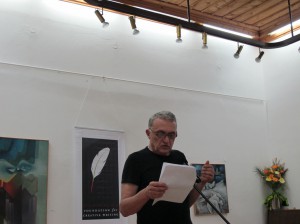

Our caesura was ably captained by this man.

We snapped the picture of our captain and rushed back into the maelstrom of the seminar. Except for the late evenings (the heavy-lifting period), we were busy with workshops and panels and readings until we boarded the bus for Sofia on May 31 with a sorrowful goodbye to lovely Sozopol, but perhaps a measure of gratitude that we could finally rest.

The program ended with a reading the evening of Tuesday, June 1. If I left for the U.S. the next morning, I could be back at work Friday. Taking one more day off work meant three more days in Bulgaria, an obvious conclusion I thought everyone would come to.

They did not.

Fellow American Kelly Luce stayed an extra day. We walked around Sofia, a city in which everything is within walking distance, and we talked about the seminar, the town of Sozopol, and the Bulgarians and Americans we’d so recently met and were already missing. We walked past the long stone water feature in front of Vasil Levski National Stadium and followed the paths into a hilly wooded area of Borisova gradina. We also went to the churches—the ancient brickwork of the Church of Sveti Sofia (where the city gets its name) and the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, which is not only a grand church topped by gold and verdigris domes, but has a bustling marketplace out front. At this bazaar, Kelly helped me buy gifts (filigreed jewelry, a million lev note, and a Russian doll, among other items) and gave me tips on how to haggle with the vendors. On a fence made of plywood around a building that had apparently been under construction for years, we saw breathtaking graffiti in English and Bulgarian.

Fellow American Kelly Luce stayed an extra day. We walked around Sofia, a city in which everything is within walking distance, and we talked about the seminar, the town of Sozopol, and the Bulgarians and Americans we’d so recently met and were already missing. We walked past the long stone water feature in front of Vasil Levski National Stadium and followed the paths into a hilly wooded area of Borisova gradina. We also went to the churches—the ancient brickwork of the Church of Sveti Sofia (where the city gets its name) and the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, which is not only a grand church topped by gold and verdigris domes, but has a bustling marketplace out front. At this bazaar, Kelly helped me buy gifts (filigreed jewelry, a million lev note, and a Russian doll, among other items) and gave me tips on how to haggle with the vendors. On a fence made of plywood around a building that had apparently been under construction for years, we saw breathtaking graffiti in English and Bulgarian.

We went back to our rooms after our walk, but mine was being made up, so I went to a shop I’d noticed earlier to buy a gift for my niece. As I left the store, I saw a businessman in a gray suit standing stock still. Then I noticed the siren in the distance. I turned a corner and saw over a dozen more people standing completely still, as if they were listening for something, waiting for instructions. It felt like the Bulgarian version of a tornado siren. I thought we would be told what to do, but no instructions came.

Back at the hotel, I asked what the siren meant, and they told me the story: On June 2, 1876, shortly after noon, Christo Botev crossed the Danube with 200 Austrians in the hope of inciting and leading a Bulgarian revolution against the Ottomans. He and all his men were killed. Every year on that date at that time, a siren goes off and everyone stays still for one minute to commemorate his sacrifice—no one speaks, no one moves except ignorant tourists.

Thursday, June 3, I wandered Sofia alone. I visited the Sofia Military Museum, a well-presented museum on the edge of the city, outside of which are dozens of tanks, planes, helicopters, and jeeps from World Wars I and II and the Soviet Era. After the long walk (which included getting lost) to the museum, I arrived with only forty-five minutes to see the impressive galleries of military history from ancient times—when the Thracians fought the Greeks and Romans—through the Second World War. That night I also visited Hambara, my vote for coolest bar in the world, one last time. Built in an old barn, as far as I could see there were no electric lights in the place, just dozens if not hundreds of small candles the staff replaced every few hours. The bar has no sign outside, and I almost couldn’t find it despite the fact that I’d been there twice before.

Thursday, June 3, I wandered Sofia alone. I visited the Sofia Military Museum, a well-presented museum on the edge of the city, outside of which are dozens of tanks, planes, helicopters, and jeeps from World Wars I and II and the Soviet Era. After the long walk (which included getting lost) to the museum, I arrived with only forty-five minutes to see the impressive galleries of military history from ancient times—when the Thracians fought the Greeks and Romans—through the Second World War. That night I also visited Hambara, my vote for coolest bar in the world, one last time. Built in an old barn, as far as I could see there were no electric lights in the place, just dozens if not hundreds of small candles the staff replaced every few hours. The bar has no sign outside, and I almost couldn’t find it despite the fact that I’d been there twice before.

Friday, I went to the Archeological Museum, filled with Thracian, Greek, and Roman artifacts, including a Roman-era “statue of a woman with a head that does not pertain to her” (a phrase that resonated with me). After, I had lunch with Milena Deleva, a woman of apparently limitless energy who directs the Elizabeth Kostova Foundation. She was our primary contact with the foundation leading up to the seminar and organized everything from our hotels in Sofia and Sozopol to who would translate our story excerpts into Bulgarian. She scheduled all our meals, which included arranging—with no notice whatsoever—an alternative to the outdoor restaurant where we had reservations on the one night in Sozopol there were thunderstorms. In addition to all that, when I lost my bag during the panel on literary diplomacy in Sofia, she was the one who knew where it was. Friday evening found me at an art opening with my Sozopol roommate, Ivan Dimitrov, who met me after an interview at a local radio station about his new novel. The opening was a Lewis Carroll-inspired take on the artist’s time in Amsterdam, and in addition to the photos and texts lining the walls, it featured live rabbits, a musician playing a didgeridoo, little girls dressed as Alice, and actors playing Amsterdam prostitutes. Saturday morning, June 5, at 6:35 am, my plane left Sofia airport.

At the end of the Beatles song “A Day in the Life,” there’s this long orchestral crescendo, strings, brass, reeds, percussion all improvising up the scale as the volume increases. The crescendo ends when multiple E-Major piano chords are struck simultaneously. On my iPod, those chords take forty-one seconds to quiet. It’s like the song is trying to hold onto itself, not give up what has come before, not fade into silence. My last three days in Sofia were like that. I wandered Sofia taking in the sights and sounds of the city while simultaneously replaying conversations from Sozopol, trying to hold onto the feeling of the sun and the wind in my hair as I ate lunch on the terrace overlooking the Black Sea.

At the end of the Beatles song “A Day in the Life,” there’s this long orchestral crescendo, strings, brass, reeds, percussion all improvising up the scale as the volume increases. The crescendo ends when multiple E-Major piano chords are struck simultaneously. On my iPod, those chords take forty-one seconds to quiet. It’s like the song is trying to hold onto itself, not give up what has come before, not fade into silence. My last three days in Sofia were like that. I wandered Sofia taking in the sights and sounds of the city while simultaneously replaying conversations from Sozopol, trying to hold onto the feeling of the sun and the wind in my hair as I ate lunch on the terrace overlooking the Black Sea.

I mentioned at the beginning that the silence in the moments we watched the dolphins allowed me to hear the music within the noise of the seminar. What I want now—what I’ve wanted since I returned to the U.S.—is to hold onto that music within the silence that follows.

Further Links and Resources:

The 2011 Sozopol Fiction Seminars will take place next year May 26th to 31st.

The 2011 Sozopol Fiction Seminars will take place next year May 26th to 31st.

Ten scholarships to attend the Sozopol Fiction Seminars will be given to five fiction writers working in English and five working in Bulgarian. The Elizabeth Kostova Foundation will cover tuition fee, room and board, in-country transportation, and 50% of the international travel expenses. Writers of any nationality are eligible.

Using the online submission system, submit 10-20 pages of fiction, a personal statement, a curriculum vitae, artistic statement, and a letter of reference by February 15, 2011.

Visit the EKF Website for complete guidelines. You may also write Milena Deleva, the Director of the Elizabeth Kostova Foundation: mdeleva@ekf.bg

Kelly Luce’s collection of Japan-set stories received the San Francisco Foundation’s 2008 Jackson Award and was a finalist for the 2010 Bakeless Prize. The title story, “Ms. Yamada’s Toaster,” was awarded Tampa Review’s 2008 Danahy Prize. Her work has been recognized by fellowships from the MacDowell Colony and Jentel Arts, and can be found in The Southern Review, Massachusetts Review, Crazyhorse, Nimrod, The Gettysburg Review, and other journals. This spring, she was the Writer in Residence at the Kerouac House in Orlando; in July, she attended the Sewanee Writers Conference as a Scholar.

Kelly Luce’s collection of Japan-set stories received the San Francisco Foundation’s 2008 Jackson Award and was a finalist for the 2010 Bakeless Prize. The title story, “Ms. Yamada’s Toaster,” was awarded Tampa Review’s 2008 Danahy Prize. Her work has been recognized by fellowships from the MacDowell Colony and Jentel Arts, and can be found in The Southern Review, Massachusetts Review, Crazyhorse, Nimrod, The Gettysburg Review, and other journals. This spring, she was the Writer in Residence at the Kerouac House in Orlando; in July, she attended the Sewanee Writers Conference as a Scholar.

A graduate of Oberlin College and the University of Michigan MFA program, Carin Clevidence is the recipient of a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award and a fellowship from the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, MA. Her short stories have appeared in Story, the Indiana Review, the Michigan Quarterly Review, and FiveChapters, among others, and her travel writing in Grand Tour and the Asahi Weekly of Japan. Her first novel, The House on Salt Hay Road has just been published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

A graduate of Oberlin College and the University of Michigan MFA program, Carin Clevidence is the recipient of a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award and a fellowship from the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, MA. Her short stories have appeared in Story, the Indiana Review, the Michigan Quarterly Review, and FiveChapters, among others, and her travel writing in Grand Tour and the Asahi Weekly of Japan. Her first novel, The House on Salt Hay Road has just been published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Paul Vidich is a graduate of the Rutgers-Newark MFA program. His stories have appeared in online literary journals and have been finalists in Glimmer Train contests, the 2009 Richard Bausch Short Story Contest, and the 2008 Raymond Carver Award for New Writers. He is a board member of Poets and Writers.

Paul Vidich is a graduate of the Rutgers-Newark MFA program. His stories have appeared in online literary journals and have been finalists in Glimmer Train contests, the 2009 Richard Bausch Short Story Contest, and the 2008 Raymond Carver Award for New Writers. He is a board member of Poets and Writers.

Charles Conley, born and raised on Long Island, is a 2009-2010 fellow at Teachers & Writers Collaborative in New York and was a 2008-2009 fellow at the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center. His stories have appeared in The Southern Review and The Harvard Review and are forthcoming in North American Review and Canadian Notes and Queries. He is the recipient of an Elizabeth George Foundation Grant in 2010 and a SASE/Jerome Grant for Emerging Writers in 2007. He received his MFA from the University of Minnesota.

Charles Conley, born and raised on Long Island, is a 2009-2010 fellow at Teachers & Writers Collaborative in New York and was a 2008-2009 fellow at the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center. His stories have appeared in The Southern Review and The Harvard Review and are forthcoming in North American Review and Canadian Notes and Queries. He is the recipient of an Elizabeth George Foundation Grant in 2010 and a SASE/Jerome Grant for Emerging Writers in 2007. He received his MFA from the University of Minnesota.