When I was sixteen, I found a coffee-stained copy of Raymond Carver’s Where I’m Calling From left behind on the table of a local café. From the opening lines of the collection’s first story, I was captivated by the precision of the writing. As I finished each story, I would close the book and flip to the photograph of Carver on the back cover. The contrast between the stories and that image of the author confused me.

When I was sixteen, I found a coffee-stained copy of Raymond Carver’s Where I’m Calling From left behind on the table of a local café. From the opening lines of the collection’s first story, I was captivated by the precision of the writing. As I finished each story, I would close the book and flip to the photograph of Carver on the back cover. The contrast between the stories and that image of the author confused me.

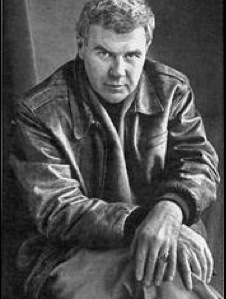

In Marion Ettlinger’s stark black-and-white portrait of Carver, the author sits hunched forward slightly, his hands crossed at the wrists and resting on this knee. He wears a supple leather bomber jacket, a wool scarf, and a broad ring on one of his fingers. Carver looks comfortable, untouched by life’s rough edges, a slight smirk seems to be growing at the edges of his mouth.

Marion Ettlinger's photo of Carver, from http://www.nancykiefer.com/

I remember thinking, “How could this guy know so much about these characters?”

I was sixteen, and still naively believed that the narrator of every first-person story must be the author himself. Right? I mean, I was writing self-absorbed, autobiographical poems and stories every day. Wasn’t everyone else?

But back then I had no idea of the difference between sympathy and empathy. And, most importantly, I had no idea of what the imagination was capable of.

When I discovered the writing of Andre Dubus in my early twenties—beginning first with his final collection, Dancing After Hours (Knopf, 1996), and then quickly devouring his entire catalog—I discovered complex work that both taught me about the literary craft of compression and point of view in short stories, and gave me a deeper understanding of empathy and compassion as a human being.

As I read Dubus’s work, I also sought out all that had been written about him. In the latter, too often I stumbled upon other writers and scholars seeking to make tenuous links between the characters that inhabit Dubus’s tough yet celebratory stories, and Dubus’s actual life. Such reductive readings frustrated me. By then, I’d come to understand the difference between art and life, between the writer and the writing.

For no other apparent reason than the sake of putting fiction into neat boxes, some scholars seem to regularly seek out the explanation of fiction in the autobiography of authors. These scholars cling to ease rather than aspiring to generate objective knowledge and insights. They claim to admire a writer, yet diminish their work by putting forth essays and papers full of feeble examples of how the author’s work is thinly veiled autobiography.

Dubus himself said he steered clear of autobiography in his fiction. “I’ve always fought writing autobiography,” he told Kay Bonetti in a 1984 interview for the American Audio Prose Library series. ”I’ve felt that there was something wrong with it. I guess in my early twenties I started thinking about my choice of subjects and worried then that if I spent too much time writing autobiography I’d lose touch with the world.”

Unsurprisingly, that conversation with Bonetti eventually got around to Dubus’s literary hero, Anton Chekhov. In Dubus’s own words, we discover that what the short story devotee really sought to achieve with his art were stories devoid of himself. Explaining Chekhov’s reaction to an editor’s praise for his piece “A Dreary Story,” Dubus told the interviewer: “What [Chekhov] wrote to his editor about that story is absolutely true, it is full of arguments and philosophical debates, and Chekhov said, ‘but you will not find me in there.’ And that’s what I like.”

Recently, I sought input from several authors about the idea of autobiography in fiction. Many of the authors I spoke with have themselves, in varying degrees, dealt with their own writing being questioned as to its autobiographical elements.

Christopher Tilghman, author of the novels Mason’s Retreat (Random House, 1996) and Roads of the Heart (Random House, 2004), as well as the story collections The Way People Run (Random House, 1999) and In a Father’s Place (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1990), is unequivocal about his feelings on the matter of fact versus fiction in Dubus’s short stories.

Christopher Tilghman, author of the novels Mason’s Retreat (Random House, 1996) and Roads of the Heart (Random House, 2004), as well as the story collections The Way People Run (Random House, 1999) and In a Father’s Place (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1990), is unequivocal about his feelings on the matter of fact versus fiction in Dubus’s short stories.

“On the subject of using personal material in fiction,” says Tilghman, “I tend to think of Andre as one of the least autobiographical writers I know.”

In 1987, Tilghman became a founding member of the writers’ group that met nearly weekly in Dubus’s living room until his death in early 1999. The group eventually became known at the “Thursday Nighters,” a term coined by Tilghman. Dubus chronicled some of the group’s particularly difficult growing pains in his essay “Letter to a Writer’s Workshop,” collected in Meditations from a Moveable Chair (Knopf, 1998).

“If there are specific incidents in any of his stories that were drawn from life, his literary and spiritual project simply subsumed them. Whatever residue of personal experience that survives is simply not recognizable as autobiography,” continues Tilghman. “And to the contrary point, Andre seemed to have used fiction as a way to place and observe himself within situations that, thankfully, he never did experience in his waking life.”

It is not voyeurism that readers seek in Dubus’s stories, says Tilghman, but the pointed “horns of ethical dilemmas” that Dubus’s stories thrust readers between. “Many of his characters take action that we might think of as unlikely or distasteful or unlawful, but they do it because they think it is the only thing to do.”

When Tilghman met Dubus back in 1987, he was a young writer struggling to find his voice. Today, he is the director of the creative writing program at the University of Virginia. At UVA, known as the school Thomas Jefferson built, the legend of William Faulkner’s stint as a writer-in-residence in the late 1950s still looms large, as does the legacy of a certain alum: Edgar Allen Poe. Today, the acclaimed novelist and short story writer Ann Beattie serves as the university’s Edgar Allan Poe Professor of Literature and Creative Writing.

Like Tilghman, Beattie was close to Dubus. In the winter of 1987, she joined E.L. Doctorow, Gail Goodwin, John Irving, Stephen King, Tim O’Brien, Jayne Anne Phillips, John Updike, Kurt Vonnegut, and Richard Yates for a series of benefit readings in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to raise money for Dubus after he was struck by a car and handicapped. A decade later, Beattie joined Dubus for several readings together while he was on tour for what would end up being his final story collection, Dancing After Hours.

For Beattie—whose recently published novella Walks with Men (Scribner, 2010) had many reviewers pondering whether or not the author had raided her own memories of living in New York City in the 1980s in order to write the book—the question of autobiography in an author’s work is much less interesting than many other more intriguing questions.

When Beattie was in college in the late 1960s, the New Criticism model—eschewing the biographical and sociological in favor of close reading and the work itself—was a prevailing wisdom. Then, for a time, she questioned such an approach. “When I became a writer, I found this increasingly….odd,” says Beattie. “Why were we living and working, if not to admit that we were peculiar? Not that I think the key to fiction is ‘Is it autobiography disguised?’ but rather that readers might think there was a ‘key’ to better understanding the work, and that that ‘key’ turned in the lock of ‘writer’s life’.”

When Beattie was in college in the late 1960s, the New Criticism model—eschewing the biographical and sociological in favor of close reading and the work itself—was a prevailing wisdom. Then, for a time, she questioned such an approach. “When I became a writer, I found this increasingly….odd,” says Beattie. “Why were we living and working, if not to admit that we were peculiar? Not that I think the key to fiction is ‘Is it autobiography disguised?’ but rather that readers might think there was a ‘key’ to better understanding the work, and that that ‘key’ turned in the lock of ‘writer’s life’.”

“If readers do think this—as opposed to people who speak about literature, who want, justifiably, to move closer to the text, but who may therefore be led into a kind of thinking that involves verifiability—they’ve been misled about what fiction is. Both parties have misunderstood,” asserts Beattie, whose newest collection The New Yorker Stories (Scribner, 2010) collects her forty-eight pieces that appeared between 1974 and 2006 in that bellwether of American short fiction; the book was named to the New York Times Book Review 10 Best Books of 2010 list.

“Fiction mystifies the writers of fiction,” says Beattie, explaining:

They—they, alone—are quite capable of displaying the ‘facts’ of their lives, yet doing this holds almost no fascination for any fiction writer, EVER.

So while fiction writers don’t write blindly, neither do they think that facts should be warped into art. They have taken a huge step away from facts in order to write fiction. In that space—in that gap—true make-believe, true fiction, occurs. It occurs as much for the writer as for the reader. It seems to me that it’s interesting additional information if an incident really did, in point of fact, happen to the writer, but the more interesting question is: So what? Why did that capture the writer’s interest, as opposed to 1,000 other things that really happened?

The author Edie Clark has long been awed by not only the incidents and characters that captured Dubus’s interest and empathy, but by Dubus’s seemingly prophetic vision.

Clark, the author most recently of the essay collection States of Grace: Encounters with Real Yankees (Benjamin Mason Books, 2010), traveled for years from her home in New Hampshire to attend the weekly writer’s workshop at Dubus’s Massachusetts home; Clark’s searing memoir of losing her young husband to cancer, The Place He Made (Villard, 1996), was written and drafted during those workshops.

Clark, the author most recently of the essay collection States of Grace: Encounters with Real Yankees (Benjamin Mason Books, 2010), traveled for years from her home in New Hampshire to attend the weekly writer’s workshop at Dubus’s Massachusetts home; Clark’s searing memoir of losing her young husband to cancer, The Place He Made (Villard, 1996), was written and drafted during those workshops.

“What always struck me so deeply about Andre,” says Clark, “was how some of his stories turn out to be his life, rather than the other way around. Like he was prescient.”

Clark served for many years as the fiction editor of Yankee magazine and published many stories and essays by Dubus, as well as work by Donald Hall, Stephen King, John Updike, and Monica Wood, among many others. In particular, Clark remembers an eerie, seemingly prophetic Dubus story that came across her desk.

In 1986, Clark had Dubus’s story “Blessings” in production for the next issue of Yankee. The story, later collected in Dancing After Hours, revolves around an horrific boating accident, a shark attack, and the subsequent aftermath for the survivors. “I recall counting the number of times the word ‘leg’ appears in that story,” says Clark. “Twenty-seven different times. And, of course, while we were putting that story into print, Andre lost his leg and the use of his other. I don’t think he ever put that together as the rest of his life was so dramatically changed but it wasn’t the first time I saw this, that what happened in his stories preceded what happened in his own life.”

But, of course, Dubus’s stories don’t always fall into this prescient category—a category, it could be said, that exists for an honest writer engaged in writing about their own fears and the what-ifs of life. In Clark’s opinion, Dubus both used kernels of his life as seeds for stories, and he listened closely to the stories of others to inspire his art. For years, Clark kept a long quotation from Dubus’s essay “Marketing” (from Broken Vessels, Godine, 1991) tacked to the wall beside her desk. The quote, the essay’s opening paragraph, reads:

I love short stories because I believe they are the way we live. They are what our friends tell us, in their pain and joy, their passion and rage, their yearning and their cry against injustice. We can sit all night with our friend while he talks about the end of his marriage, and what we finally get is a collection of stories about passion, tenderness, misunderstanding, sorrow, money; those hours and days and moments when he was absolutely married, whether he and his wife were screaming at each other, or sulking about the house, or making love. While his marriage was dying, he was also working: spending evenings with friends, rearing children; but those are other stories. Which is why, days after hearing a painful story by a friend, we see him and say: How are you? We know that by now he may have another story to tell or he may be in the middle of one and we hope it is joyful.

“Andre thought deeply about life,” says Clark, “and about what happened to his friends, because he cared but also because he wanted to understand how the world worked.”

In Dubus’s own remarks we find how consistently he looked outward to find the stories he wove, such as in a 1985 interview with Thomas Kennedy for Revue Delta. Dubus was open about the very simple inspiration that led him to write Voices from the Moon (Godine, 1984), a story that is both his longest novella and very likely his masterpiece: Dubus told Kennedy that he came upon the story’s plot while reading the Boston Globe one day.

In Dubus’s own remarks we find how consistently he looked outward to find the stories he wove, such as in a 1985 interview with Thomas Kennedy for Revue Delta. Dubus was open about the very simple inspiration that led him to write Voices from the Moon (Godine, 1984), a story that is both his longest novella and very likely his masterpiece: Dubus told Kennedy that he came upon the story’s plot while reading the Boston Globe one day.

The nine chapters of the 126-page Voices from the Moon alternate between Richie Stowe, a serious twelve-year-old who plans to become a priest, and the other members of the boy’s family. The story takes place over the course of a single day and is centered on the revelation that Richie’s divorced father plans to marry the ex-wife of Richie’s older brother—the father’s own former daughter-in-law.

“Woman in her 20s who wanted to marry a man in his 40s who was her ex-husband’s father,” said Dubus on the newspaper article. “Against the law in Massachusetts and in some other states. That was the whole thing. I tried to make up the characters who went with them.”

In the end, Clark doesn’t believe that it matters either way whether the kernel of a Dubus story came from his own experience, a friend’s life, or from a newspaper article. “The point is,” she says, “that Andre recognized transformative moments in life, whether in his own or in that of his friends, and turned them into art. He understood what it means to be human.”

The Pulitzer Prize-winning author Richard Ford is renowned for capturing the transformative moments in life. He is also no stranger to having his fiction confused for his life.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning author Richard Ford is renowned for capturing the transformative moments in life. He is also no stranger to having his fiction confused for his life.

“It’s happened to me a lot,” Ford told me recently, “that novels and characters I’ve written have, by readers, been confused with my life and self. In one way, I suppose, it ought to be flattering. It means the illusion of the book was fairly complete, or at least it seemed ‘true to life.’”

While Ford solidified his reputation as a master of the American short story with his early collection Rock Springs (Atlantic Monthly, 1987), it was his 1986 novel The Sportswriter (Vintage) that thrust his fiction into the American consciousness. The voice of Ford’s narrator Frank Bascombe, an American Everyman set adrift in New Jersey, has resonated with readers both in the States and abroad. Ford has since taken Bascombe through the subsequent novels Independence Day (Knopf, 1995) and Lay of the Land (Knopf, 2006).

Ford, who included Dubus’s story “Killings” when he edited the anthology The New Granta Book of the American Short Story (Granta Publications, 2007), has been charged by some critics with using Bascombe as a mouthpiece of his own views. The author, however, insists that very little, if anything, about Frank is autobiographical.

“I’m always trying,” says Ford, “to give Frank responses to things that I’ve never had—and maybe once I’ve seen them ascribed to him, wouldn’t want.” If he slips and lets a little Ford into Frank, he sees it as a weakness that needs correcting. “I think to myself,” he says, “’Gee whiz, what a failure you are. Is that all you can do, just to give him some point of view, some opinion, some response that you yourself have already had?’”

“I’m always trying,” says Ford, “to give Frank responses to things that I’ve never had—and maybe once I’ve seen them ascribed to him, wouldn’t want.” If he slips and lets a little Ford into Frank, he sees it as a weakness that needs correcting. “I think to myself,” he says, “’Gee whiz, what a failure you are. Is that all you can do, just to give him some point of view, some opinion, some response that you yourself have already had?’”

Ford, who says he came to Dubus’s stories later in his life, notes that even when kernels of fact occasionally find their way into fiction, they are quickly mutated by the very act of storytelling. “Of course, these bits of oneself migrate into pieces of fiction—both advertently and inadvertently,” says Ford:

But they never get there in a pure state. Events are events; people are people. But characters are made entirely of language, and come onto the story’s stage through a process of authorial choice, misadventure, fortuity, editorial acumen, and really a lot of other courses—all of which fundamentally change them from being real people, assuming they were real people to being with—which frankly they mostly weren’t.

In fact, Ford finds the act of attempting to wedge real people into fiction to be harmful to the creative act:

Writing real people into fiction is hazardous, as many writers have pointed out, and I myself know to be true. Real people, whom you might want to install in your story, turn out to be intractable. They tend to stay themselves and be hard-sided, and not the infinitely mutable fascicles of language real characters (versus real people) are. Made-up characters are lambent, they mutate, they surprise, they act out of character, and are therefore to be prized—for this freedom alone.

In the end, Ford believes such reductive readings of fiction do not merely minimize his work or that of his peers, but diminish the human potential of the mind. “The assertion that characters in fictions are just real people put onto the page offends me by selling the imagination short, by reducing all things fictive to the personal, to the known, to the flesh—as if that’s really where reality lies. It’s not. Reality’s dull, dull, dull without the imagination to show it the way outward from itself,” says Ford.

Are biographical readings always wrong? No. Are biographical readings but one limited lens through which to explore fiction? Absolutely.

Writers discover and tell stories for reasons that often remain a mystery to the writer themselves. Dubus himself could only speculate on why many of his characters so often struggle with loneliness, heartache, violence, adultery, rape, murder, and abortion. “I think honest writers write about what bothers them,” he once opined.

“My guess is that surprise is the variable,” speculates Ann Beattie when she considers what it is that captures a writer’s interest and sends them spelunking into the depths of a story:

You can be surprised at the simplest, most ordinary things, like that the houseplant wasn’t done flowering; that it was winter and it snowed; that you boiled water and put something in the pot and, by golly, out came pasta. So: writers are not special creatures, hyper-aware and hyper-sensitive. Rather, they are ordinary or dumb creatures, who—for whatever reason—have decided not much is lost if they are to be vulnerable, and to make something of their surprise when confronting ordinary life. To look at ordinary life in an unusual way—a lingering way—tinges it. If the color and contrast takes, that’s what fiction is. Fiction is like a big, absorptive blotter.

In the end, no one—no scholar, nor his children, family, or friends, not even the author himself—can truly give us impartial insight into Dubus’s fiction. Fiction need only be true to itself.

In the end, no one—no scholar, nor his children, family, or friends, not even the author himself—can truly give us impartial insight into Dubus’s fiction. Fiction need only be true to itself.

On February 23, 1999, the day before Dubus died, he gave a brief interview to Greg Garrett. When asked how he wrote dialogue that is “so real,” Dubus insisted that it wasn’t in the least bit real; it was, he said, human speech purified to a poetic rhythm. “We’re not trying to be real,” Dubus told the interviewer, on what he did not know then was the last afternoon of his life. “We’re trying to be better than real. We’re trying to be true.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: One damp weekend in April 2010, I attended a symposium on Andre Dubus and Andre Dubus III at Saint Anselm College in Manchester, New Hampshire. I’d been invited by Dr. Edward Gleason. Ed and I had communicated by email a couple years earlier when he gave me permission to include his beautiful black-and-white photographs of Andre Dubus with my essay on the short story master for Poets & Writers magazine; Ed’s photographs are believed to be the last ever taken of Dubus before his death.

During the symposium, I was somewhat disturbed by the constant assumptions by many of the presenting academics that Dubus’s masterful fiction was simply thinly veiled autobiography.

After the symposium, Ed asked me to contribute an essay to the special Dubus tribute edition edition of the Xavier Review published in December 2010. I appreciated Ed’s support in allowing me to contribute an essay that, in some ways, sought to debunk the work of other Dubus scholars. I thank the Xavier Review for first publishing this essay, and supporting its republication here.

The Stakes Are Absolute

Three Questions on Andre Dubus with Todd Field

Todd Field, image via Wikipedia

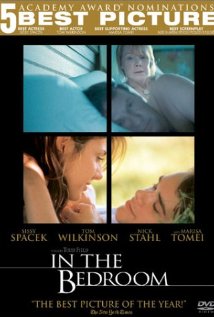

With the 2001 film “In the Bedroom,” director Todd Field became the first person to bring Andre Dubus’s fiction to life on the screen. Field worked with co-writer Rob Festinger to adapt the screenplay from Dubus’s taut short story “Killings.” After premiering at the Sundance Film Festival, the film went on to earn five Academy Award nominations, including Best Adapted Screenplay.

On the evening of February 23, 1999, Dubus called Field—who was well underway with “In the Bedroom”—to wish him an early “Happy Birthday.” The next morning, Dubus died of a heart attack. Field was the last person to ever speak with him.

Field and I spoke briefly about his interest in Dubus’s prose, and his work adapting it.

Joshua Bodwell: Of all Dubus’s work, why did you to select “Killings” to adapt into a feature-length film?

Todd Field: The most exciting thing as a reader is to come across someone’s material—a short story or novel—that you can’t stop thinking about—to become haunted by an impression. In 1992 I was a directing fellow at the American Film Institute. The first year we were allowed to make whatever we liked so long as the running time wasn’t in excess of thirty minutes. We weren’t permitted to show our work outside the conservatory, and so there was no fiscal obstacle of having to secure standard literary rights. That year we were required to make three films. The first two were original, but for the third I wanted something to adapt, and someone recommended Andre Dubus. The first book I got my hands on was Collected Stories and it was like discovering a new country where all the relatives you’ve never met live. Two days later I’d camped on three of Andre’s stories— “Killings,” “Delivering,” and “The New Boy.” Of the three, “Killings” was the most powerful in terms of theme and breadth, but for those same reasons it was definitely not a 30-minute film. “Delivering” is the story I ended up adapting, and to this day is the film I’m most fond of in terms of execution and process. But “Killings” kept on nagging at me. In large part because Matt Fowler reminded me so much of my father, a man you would never imagine violating his own nature in such a way. When it came time to make a feature length film there was no question that it would be anything but “Killings.”

Bodwell: One of the major changes you made in adapting “Killings” into In The Bedroom was making Frank Fowler an only child, whereas in the story he had a brother. Can you talk about that decision?

Field: The stakes are absolute for the Fowlers, leaving them just each other, without any other immediate family, to mitigate their grief. This is something I witnessed first hand when, sadly, one of my dearest friends, an only child, was murdered at twenty-one.

Bodwell: Could you talk a bit more about why you feel that your film adaptation of “Delivering” was so artistically satisfying?

Field: “Delivering” is a wonderful character study that explores, over the course of a single day, some of the complicated dynamics of brotherhood. In this case an older, stronger brother trying to sort out how to protect his younger, not particularly athletic, sibling from something he knows will hurt him emotionally. But that same afternoon the older brother too becomes worried about the physical safety of their father. In the end he decides he must inflict physical pain on his younger brother to get his father’s attention, ultimately, at least in his mind, saving them both. The story is really perfect, and Andre, who would sometimes take years working on a story, told me that “Delivering” was really the only time he ever sat down and wrote something in a single sitting. That didn’t surprise me, because it does have a peculiar kind of momentum. We all experienced something similar making it. “Delivering” was photographed and edited very quickly in just four days.

Further Links and Resources

From “The Times Were Never So Bad” from Edward Delaney on Vimeo.