Editor’s Note: For the first several months of 2022, we’ll be celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts.

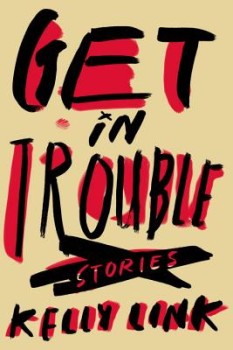

In today’s feature, Alice Sola Kim and Kelly Link discuss Link’s collection Get In Trouble, with a close look at the process behind two stories. The interview was originally published on May 29, 2015.

I met Kelly Link when she was one of my teachers at the Clarion West Writers Workshop in 2004. Literary brilliance isn’t always coupled with wicked pedagogical chops, but in Kelly, it is. She was immediately warm and funny, and could deliver piercing insights into the ways in which our stories were broken without breaking us. (I mean, she said nice things too, but that’s a little easier.) And when we read her stories, we were knocked off our feet and had little x’s for eyes.

Reading Kelly’s work is an indescribable experience that I recommend to everyone. In describing Kelly’s stories, you could focus on the wild breadth of inspiration, how they fold into themselves many different genres and embodiments of the fantastical without becoming any one thing in particular. Or, you could focus on the prose itself—the lightness of her touch, the sly humor, the deep, weird, suggestive depths of those beautiful and beautifully simple sentences. Perhaps what it comes down to is that what Kelly does feels very new and very, very old—tale-told-around-a-fire-old—at the same time.

In addition, to use a designation that might be pleasing to Kelly herself, she’s somewhat of an original vampire. (I might be using this term incorrectly but I want to use it because it’s from one of her favorite shows.) As a writer, teacher, and editor, Kelly has mentored and influenced untold people, in the disparate (but becoming less so) spaces of science fiction conventions and AWP and YA and MFAs and so on. Through interactions with her and her work, writers and readers are inspired to go outside of their norms in the best ways possible.

In this conversation, we discuss Dockers, teaching, productive time-wasting, and most importantly, Kelly’s stunning new collection of stories, Get In Trouble (Random House). Kelly also gives us a deep dive into her writing process for two of the stories in particular: “I Can See Right Through You” and “The Lesson.”

Along with Get in Trouble, Kelly Link is the author of the collections Stranger Things Happen, Magic for Beginners, and Pretty Monsters. Her short stories have been published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, The Best American Short Stories, and Prize Stories: The O. Henry Awards. She has received a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. She and Gavin J. Grant have co-edited a number of anthologies, including multiple volumes of The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror and, for young adults, Steampunk! and Monstrous Affections. She is the co-founder of Small Beer Press and co-edits the occasional zine Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet.

Interview:

Alice Sola Kim: Your latest story collection, Get in Trouble, burst in like the Kool-Aid man earlier this year to blow all of our minds. As it’s your fourth story collection, I was wondering what you found to be different about it from your previous books—whether it’s the stories themselves or extra-literary factors like the publication process or reception.

Kelly Link: In my head, the Kool-Aid man and the woman from the Electric Company who yells, “HEY YOU GUYS” are more or less the same person. I always found them both very alarming which, I suppose, is the point of them.

The writer is perhaps the last person to ask what’s different, book to book. But maybe I can put my finger on a couple of things. These stories mostly run long. I didn’t manage any classic length short stories (4,000 to 6,000 words) this go round. The central characters all behave in more extravagant ways. There’s a lot of drinking and probably more vomit than there should be. Consequences! I began to notice, writing these stories, that I was alternating between adolescent and middle-aged protagonists and that certain elements seemed to carry over story to story, so there are a couple of odd pairings: “Origin Story” and “Secret Identity”; “The New Boyfriend” and “I Can See Right Through You.”

Certainly being published by Random House been different, by which I mean fancier and more fun. Not that publishing myself wasn’t fun! But I’m smitten with the team of people I’ve had the chance to work with, from my editor Noah Eaker to the publicists Maria Braeckel and Henley Cox and Sarah Goldberg. I didn’t expect to enjoy giving up control over the publication process so much. This go-round I’ve gotten to be just the writer, rather than the writer, the art director, and the publisher.

Yeah, I can only imagine if I were asked this question, I’d yell defensively, “Stuff! I don’t know!” One thing I really loved to do while reading Get in Trouble was look at the stories through the lens of its title. What a great title—aren’t the best invitations mixed with warnings? It, and the content of the stories themselves, compelled me to think a lot about morality—the choices the characters make, what “trouble” means from story to story, who gains and loses because of this trouble—and clarified even further the sense of dazzle and heartbreak and delight present in this book, and all of your work.

Yeah, I can only imagine if I were asked this question, I’d yell defensively, “Stuff! I don’t know!” One thing I really loved to do while reading Get in Trouble was look at the stories through the lens of its title. What a great title—aren’t the best invitations mixed with warnings? It, and the content of the stories themselves, compelled me to think a lot about morality—the choices the characters make, what “trouble” means from story to story, who gains and loses because of this trouble—and clarified even further the sense of dazzle and heartbreak and delight present in this book, and all of your work.

To mention something totally different that I loved, I thought it was amazing when Dockers photographed Get in Trouble with some pants and a sweater and tweeted that photo out, which seems like the kind of experience specific to being with a big publishing house.

Dockers! I am, most of the time, anti pants. But I really like random things being put together, for example, my book with pants. Did you know that there was a German paperback publisher who, at one point, would insert into their translations of American science fiction/fantasy brief scenes in which the characters stopped to have a cup of soup? When I heard this, I became wildly envious of any writer whose book had had a soup scene added into it.

Amazing. It’d also be pretty cool to be the person whose job it was to write science fictional soup scenes. I have another question about difference: I’m curious whether you thought of any of the stories in Get In Trouble as outliers, aka “one of these is not like the others,” in terms of your writing process or subject matter or how you felt about it.

I’m curious, too, if you have an opinion on this. The last two stories I wrote for Get in Trouble were “I Can See Right Through You” and “The Lesson.” “I Can See Right Through You” was a pain in the ass. I wanted the first third to work in a particular way—to be disjointed, jumpy, to alternate seemingly in a patternless way between second person and third as much as possible. It took about a year to get the first twelve pages down, and figure out which pieces of which storylines needed to be included, and how much space to give them to let them breathe. I wanted a kind of O’Henry moment where the reader might feel satisfyingly blindsided by what happens at the end. There are all kinds of substitutions going on in that story—demon lover for demon lover, ghost for ghost, mysterious disappearance for mysterious disappearance—so I spent a lot of time thinking about the technical issues involved in that kind of sleight of hand, as well as the issues of pacing involved in writing a ghost story—how to build a sense of menace, what kind of awful thing would the main character actually do (Holly Black kept saying to me, well, what he does isn’t actually that bad, compared to what you could have him do), and atmosphere! There’s a lot more description of place in that story than I usually go in for, which means I had to figure out how balance all of that out. That story still seems to me almost like a math equation. Calculus.

I’m curious, too, if you have an opinion on this. The last two stories I wrote for Get in Trouble were “I Can See Right Through You” and “The Lesson.” “I Can See Right Through You” was a pain in the ass. I wanted the first third to work in a particular way—to be disjointed, jumpy, to alternate seemingly in a patternless way between second person and third as much as possible. It took about a year to get the first twelve pages down, and figure out which pieces of which storylines needed to be included, and how much space to give them to let them breathe. I wanted a kind of O’Henry moment where the reader might feel satisfyingly blindsided by what happens at the end. There are all kinds of substitutions going on in that story—demon lover for demon lover, ghost for ghost, mysterious disappearance for mysterious disappearance—so I spent a lot of time thinking about the technical issues involved in that kind of sleight of hand, as well as the issues of pacing involved in writing a ghost story—how to build a sense of menace, what kind of awful thing would the main character actually do (Holly Black kept saying to me, well, what he does isn’t actually that bad, compared to what you could have him do), and atmosphere! There’s a lot more description of place in that story than I usually go in for, which means I had to figure out how balance all of that out. That story still seems to me almost like a math equation. Calculus.

“The Lesson” was the last story, and I very much wanted it to have a different kind of weight to all the others. I decided at the start that there wouldn’t be any fantastic element in it, which was a useful rule to have until I got to the point where I had to figure out what kind of taxidermied animal I was going to put in the beach house, and nothing seemed quite right. So I came up with an imaginary animal. Since it was going to be a realistic story, I decided to put in as many elements of contemporary life as I could that would, even forty years ago, have seemed mildly to wildly fantastical: gay marriage, interracial relationships, surrogate mothers, extraordinary rendition, destination weddings, the advances in medical technology that make it possible for a preterm baby born at 24 weeks to survive. I started the story from the last sentence and wrote it backwards for about two pages. “I Can See Right Through You” took a year and a half to write. I wrote “The Lesson” in a week. I spent a great deal of time with the sentences in “I Can See Right Through You”. Whereas, for whatever reason, I wanted the sentences in “The Lesson” to be choppy and the paragraphs to be lumpy/unwieldy/too long. That was an experiment. I have no idea how well it works for other people.

I don’t know if those two stories seem more experimental—or different in any other way—to anyone else. But I came to them with a different kind of attitude, with the desire to figure out some new approaches.

I found a lot of excitement and newness in Get in Trouble—the fuck-you-up science fiction of “Valley of the Girls,” the non-Euclidean space horror in “Two Houses”—but “I Can See Right Through You” and “The Lesson” definitely stood out. I’m fascinated by what you said about amping up certain aspects and details of contemporary life in lieu of the purely fantastical, in “The Lesson.” Can you talk about this? Does it have to do with some kind of balance you want to achieve? Was it a way of making the process of writing it more interesting to you?

I found a lot of excitement and newness in Get in Trouble—the fuck-you-up science fiction of “Valley of the Girls,” the non-Euclidean space horror in “Two Houses”—but “I Can See Right Through You” and “The Lesson” definitely stood out. I’m fascinated by what you said about amping up certain aspects and details of contemporary life in lieu of the purely fantastical, in “The Lesson.” Can you talk about this? Does it have to do with some kind of balance you want to achieve? Was it a way of making the process of writing it more interesting to you?

“The Lesson” was originally going to be a different story altogether, about a wedding guest who has a complicated friendship with the bride, and ends up becoming a substitute wife, at the end, to an obviously uncanny sort of bridegroom. The wedding was going to be on an island, there were going to be lots of wedding dresses, and the title was “The Wedding Guest” which at the time I thought would be a good collection title. Only by the time I was ready to write “The Wedding Guest,” I’d just finished writing “I Can See Right Through You” and many of the elements that I thought would go into “The Wedding Guest” I’d ended up burning through in the former story. Which was extremely frustrating. But I still wanted to write a wedding story on an island, with a bridegroom who may not ever show up, and I decided that it would be a story about a couple who are about to become parents to a preterm baby. Very obvious stuff going on here: the late bridegroom, the early baby. I wanted the baby to be offstage, neither character pregnant themselves, which meant a surrogacy. Holly Black ran through some scenarios with me, and we talked about the kinds of experiences that gay men have, trying to adopt: particularly the economic aspect. Once I’d decided to make the central couple both men, that knocked out the possibility of having any kind of supernatural pregnancy, because the idea of suggesting that a gay couple’s child is “magical” or “monstrous” in any way would push the story hard in a direction I really didn’t want it to go. I’m always trying to detach the metaphor from the fantastic element anyway, but those metaphors would have pulled the story apart.

Anyway, then I began to think of the aspects of contemporary life that seem charged with significance because they’re so newly visible: interracial marriages, very complex kinds of family units, medical advances that sustain life under very precarious circumstances. And then, thinking about monstrous bridegrooms still, there seemed to be something almost supernatural about the visible/invisible/subterranean kind of perpetual war that our country is engaged in. So I guess I was hoping that I could in some way describe realistic things in such a way that they began to feel uncanny to the reader in both joyful and unsettling ways. The taxidermy animal filled with beetles is a true story that my sister told me. I gave the bride and groom the names of two good friends (with their permission). I gave Thanh and Harper an apartment in a building in Allston where I lived, not that long ago, for a few years. Many of the feelings about the experience of having a baby in a NICU that I gave to various characters come from my own experience. So the story was an experiment in that way too. I put a lot more of my own life in it.

The idea of writing the same story over and over again is a miserable one: all of the above were ways of making myself find a new approach. And it did seem to me that the collection needed something in a different key.

Well, these stories are definitely advertisements for keeping on doing things that feel new and/or next-to-impossible. Speaking of, I read at the end of this interview you did for Electric Literature that you been thinking more about paragraphs, which “is something you do when you’re moving more into novel space.” This also made me think of this thing I heard Don DeLillo does, which is write every paragraph on a separate page. What sorts of paragraph-y or more general novel-related thoughts have you been thinking?

Well, these stories are definitely advertisements for keeping on doing things that feel new and/or next-to-impossible. Speaking of, I read at the end of this interview you did for Electric Literature that you been thinking more about paragraphs, which “is something you do when you’re moving more into novel space.” This also made me think of this thing I heard Don DeLillo does, which is write every paragraph on a separate page. What sorts of paragraph-y or more general novel-related thoughts have you been thinking?

I feel that this explains something about how Delillo’s work works. Huh. I am still in the early stages of thinking about novels. The problem is that it seems possible to do almost anything in a novel—a terrifying thought. I’m intimidated by all of that freedom. I’ve got about a paragraph of actual novel, and then a lot of thoughts about what can go into it. I’m actually working on a series of twelve 100-word stories (more or less) based around the zodiac signs. I’ve never tried to write flash fiction, but it seemed as if maybe going very, very short would help me feel less afraid of going long. I keep thinking of those golden-age science-fiction writers who would sit down and write a novel in a week or two. I may try to do it that way.

So reassuring, those writers! Like Kazuo Ishiguro when he wrote Remains of the Day in four weeks. They show that any way is the right way, pretty much. The zodiac project you’re working on makes me curious about any interests or obsessions that you have that are feeding into your creative work, a la this highly useful exercise of yours, where you just make a list of things you really like in other people’s fiction. What things/books/shows/foods/etc. are you into currently that might end up on a list like that?

Actually, I’ve never been particularly interested in either the zodiac or in flash fiction. But the writers Jedediah Berry and Emily Houk ran a Kickstarter for a story-in-cards project, The Family Arcana. They asked 12 writers to contribute 80 word horoscopes as rewards. I picked Gemini, because doppelgangers, wrote that, and liked the result. I’ve done just over half of the year. I have no idea why a combination of two things that I’m emphatically disinterested in have proved to be so useful. At some point I may type up a list of things that I find boring, and see what that leads to. I continue to be into all things vampire: The Vampire Diaries, the movies A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night and Only Lovers Left Alive. I’ve been watching old horror movies of the ’80s. Weird how particular sound effects become as dated as hairstyles or wardrobes. I’m interested in serial narratives in general, probably because they’re so far away from what short stories can achieve. Saga is a pretty terrific comic series. I’m very, very fond of Tumblr and Twitter. They’re a kind of productive distraction for the front of my brain, which is the part that’s always getting in the way of writing.

We met when you were my teacher at Clarion West. You did this thing that all of us absolutely loved, where you gave each of us a few books that you thought we’d enjoy and that would be interesting and/or inspiring somehow. We also tried to decode your book choices to try and figure out if you thought we were any good and had any hope of being writers someday (it didn’t work because all the books were good). Where does teaching fit into your writing career? Do you have a particular teaching philosophy, or something you think is most important when it comes to teaching? And is it weird when you teach and mentor so many of us and then we swarm you at conventions and all your readings?

We met when you were my teacher at Clarion West. You did this thing that all of us absolutely loved, where you gave each of us a few books that you thought we’d enjoy and that would be interesting and/or inspiring somehow. We also tried to decode your book choices to try and figure out if you thought we were any good and had any hope of being writers someday (it didn’t work because all the books were good). Where does teaching fit into your writing career? Do you have a particular teaching philosophy, or something you think is most important when it comes to teaching? And is it weird when you teach and mentor so many of us and then we swarm you at conventions and all your readings?

I didn’t know that there was any decoding going on! Oh, man. Maybe I should start underlining cryptic sentences in the books that I pass out. I’m not teaching at the moment, and I miss it. Undergraduate teaching is a separate thing—I always feel on shakier ground with undergraduate workshops or seminars. But with graduate workshops or summer workshops, it’s safe to assume that everyone wants to be there, and that you don’t have to woo them into doing work. The general goal is to facilitate discussion: get them to describe each others’ work back so that the writer under discussion can see their story from different points of view, and make decisions based on that information about whether or not they like various readings and how to undercut the readings that they don’t want or like. The second goal is to get the workshop to ask useful questions, or to point out strategies or techniques that the writer may not have thought to use to tell this particular story, but which may serve the story. The third goal is to make the workshop think about what they find satisfying about particular story shapes or genres, and why. And of course you have to keep pointing out that the real use of the workshop is not so much the feedback and praise that you get from others, but the ways in which you learn to read your own responses to what works and doesn’t work. The things you hate most in someone else’s story tell you something about what you are most defensive about (though at first you are not necessarily aware that this is so) in your own work.

I’m actually at a feminist science fiction convention right now (WisCon, in Madison, WI) where I keep running into former students as well as former instructors. It’s all very intergenerational. Last night a lot of us were all in the same space at a dance, and the music was much too loud for talking. So that was just fine.