Douglas Trevor is one of those rare and gifted writers who can bring the whole emotional register to play within a single story. In his newest story collection, The Book of Wonders (SixOneSeven Books), the silly and the sad share a room and get to know each other; opposites are tossed together, and the reactions are a marvel.

Kirkus writes of The Book of Wonders: “Trevor manages again and again to steer stories into deeper, weirder, more fascinating waters.” Characters sleep with Greek myths, get bitten in the face by raccoons, and have their dreams implanted into the minds of others. They are a strange and incredibly compelling bunch, varied in their desires but united in their longing for community—for some kind of understanding of where they truly belong. And in an increasingly isolated and adrift age, what question could be more important?

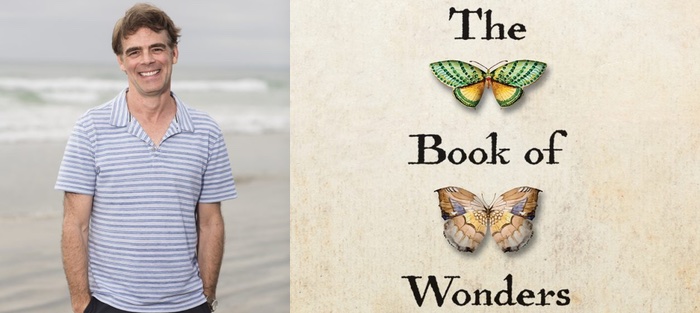

Douglas Trevor is the author of the novel Girls I Know (SixOneSeven Books, 2013), and the short story collection The Thin Tear in the Fabric of Space (University of Iowa Press, 2005). Thin Tear won the 2005 Iowa Short Fiction Award and was a finalist for the 2006 Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award for First Fiction. Girls I Know won the 2013 Balcones Fiction Prize. Doug’s short fiction has appeared most recently as a Ploughshares Solo and in The Iowa Review, New Letters, and the Michigan Quarterly Review. He has also had stories in The Paris Review, Glimmer Train, Epoch, Black Warrior Review, The New England Review, and about a dozen other literary magazines. Doug lives in Ann Arbor, where he is the current director of the Helen Zell Writers’ Program, and a Professor of Renaissance Literature in the English department at the University of Michigan.

Our interview took place at Doug’s house in Ann Arbor one afternoon over the summer; Max, his English bulldog, made sure my questions stayed within line.

Interview:

Jeff Henebury: In a previous interview with Fiction Writers Review you mentioned finding it difficult to switch from the “cadence and clock that dictates short fiction” to pacing a much longer narrative for your novel, Girls I Know. I’m curious if the reverse was true as well, returning from a novel back to short stories—was it difficult to make that transition?

Douglas Trevor: Yes, it was hard, and I actually haven’t gotten all the way back to writing short stories. I feel like my first collection was mostly comprised of classic-length short stories in manuscript form—ten to twenty, maybe twenty-five pages tops. And then I worked on Girls I Know for years, which was a 550-page book before it got shrunk down. I knew I wasn’t ready to start working on a novel when I finished that process, and I wanted to go back to short stories, but I really wanted to try longer-form stories that I hadn’t written before; I always like to try different things.

Douglas Trevor: Yes, it was hard, and I actually haven’t gotten all the way back to writing short stories. I feel like my first collection was mostly comprised of classic-length short stories in manuscript form—ten to twenty, maybe twenty-five pages tops. And then I worked on Girls I Know for years, which was a 550-page book before it got shrunk down. I knew I wasn’t ready to start working on a novel when I finished that process, and I wanted to go back to short stories, but I really wanted to try longer-form stories that I hadn’t written before; I always like to try different things.

I finished “The Librarian” first, which is the shortest of the stories in this collection, and it’s also the closest to the kinds of stories I had written before. Then I conceptualized what might be the through-line for another collection of stories—and we can talk about that in a second—but once I had established that, I wrote “The Program in Profound Thought,” which is a forty-page story. That was the length I wanted to play around with artistically, what I was interested in. You know, as a short story writer yourself, if you’re going to work in the forty-page story length, then you should probably think about a collection because publishing forty-page stories is really tricky. With that story there were some nice places that wanted to publish it but they wanted me to cut it in half—which I think would have been disastrous.

Did you like working within that longer short story length?

I love it. In fact, I just wrote a piece for Poets and Writers (September/October 2017 issue) about the novella-length story. I think it should be the apprentice form for us fiction writers, really. If you write a novella-length story as a rough draft, you get a sense at the conclusion of that process if that’s a story that you think should be reduced, or can maybe be expanded, or if it’s a story that can fit into the ephemeral, liminal space of the novella.

For me, that’s a great place to be in. If you’re trying to write the perfect fifteen-page story, you might have to cut a lot of stuff that—if you let the story breathe for a little bit—could end up going in a very different direction. I love a forty-page story. That being said, having written several of them now in the last few years, I’d like to think about moving back into a shorter form. I’ve been reading a lot of Joy Williams lately and Miranda July. These are two short story writers who often restrict themselves to a small canvas. Not doing the exact same thing I’ve done before is what I care about most. I always want every book to be really different.

Is that to keep you challenged?

It’s partly to try different things and partly to keep the process feeling fresh and new. I’m working on two novels now. One of them is in the third person and carries with it some of the challenges I experienced when writing Girls I Know. The other novel I’m working on is first person, and I haven’t worked in first person for a while; I’ve mostly done a lot of close third. So that’s something that I’m excited to do. It’s partly just being restless creatively, but it’s also partly the teaching component, too. As someone committed to teaching at an MFA program, you want to have experience working in different forms, otherwise you might become really restricted in terms of the feedback you can offer students. If you’re just a third-person writer, or if you just work in the vein of realistic fiction—whatever that means—that would seem limiting to me.

I really admire your ability to bring people from really different communities and backgrounds and put them in conversation with each other; I feel like that is something that a lot of fiction writers shy around from sometimes because it’s hard to do. Is that important for you to do as a writer?

Yeah. It’s tricky, and you can risk sounding cheesy and sentimental, but I think it’s worth the risk. Also, the question of how to create commonly held territory for different characters to interact in is something you have to think about. That’s partly why the focus of so many stories in this collection is on reading and books—the premise being that if we have a set of common texts in mind that different people can encounter, you kind of open up a space for people who are otherwise very different to at least have something to talk about. That was the idea behind “The Detroit Frankfurt School Discussion Group”; there’s a book that the German political theorist Max Horkheimer wrote that two very different people read and come to two very different conclusions about. As people they couldn’t be more different from one another, but they’ve both read the same thing. It gives them something to think through together.

As you mention, books—and the remarkably different ways we’re affected by them—are the subject of many of the stories in The Book of Wonders. When putting together a story collection, how conscious of that are you on an individual story level of that larger thematic concern? At what point did you know that books would be a through-line?

I felt pretty early on that people whose lives have orbited around books in one way or another would matter, but individual books or specific texts weren’t looming large for me. What appealed to me about the story “The Librarian” is that the character doesn’t care about reading at all; he only cares about the material contours of the book. In “The Program in Profound Thought,” there’s a little bit about what the central character—a burned-out academic—has taught and read, but largely that story is about this character getting out from under the lethargy that’s been created by his long, undistinguished, and uninspiring teaching career. I would be nervous about writing a collection that is too consistently on target. You want a collection of stories to breathe a little bit and move in different directions.

That makes sense. And we see that here—you’re exploring books and the acts of reading and writing in so many different ways here.

That makes sense. And we see that here—you’re exploring books and the acts of reading and writing in so many different ways here.

You could probably go back through and look at, you know, Winesburg, Ohio, or other collections of stories, and note the importance of reading or writing in any number of different ways. But for me what was interesting was thinking about the particular historical moment we’re at. There were quite a few fairly energetic conversations and debates in the earlier part of this century about whether or not the material book would survive very long. Were we even going to have material books around in 2015? To me, that was something interesting and scary to think about. It felt like a dangerous path we might go down. So a lot of the stories are animated by that. I think we’re still having that conversation, but that the material book has made something of a comeback in recent years. Still, it’s amazing to consider how old the technology of the printed book is, and how long it has lasted.

That kind of brings up a question I had about “Easy Rider,” which I love—it’s this story set a few decades in the future, where an author’s dreams can be neurally implanted into the minds of others. It deals with anxieties about the future of books and how we’re going to empathize with each other in the digital age.

The story’s so well-balanced—it’s not dystopic, but it’s not utopic either. I think in speculative fiction it gets easy to just throw up one’s hands and say, “We’re screwed!” But this story manages to end with unsettling, unanswered questions. I’m curious how you struck that balance—looking forward to something that’s troubling you, but avoiding easy answers?

I think that has to do with the characters you develop. When I set out, I was thinking in pretty stark terms. There have been articles about this technology in recent years—my editor sent me another one just a few weeks ago—whereby we could imagine neurally implanting the thought processes of one person into the brain of another. To me that sounds like an erasure of the self that’s troubling. But when I started to think about it through characters, trying to imagine who’d be the kind of person who’d subject herself to this kind of experiment, the character who ended up emerging is someone who’s suffered from debilitating writer’s block for decades—who hasn’t been able to write anything. In which case maybe the technology then opens up certain opportunities.

Although I think from [main character] Charity’s perspective—that story’s also about appropriation, right? Cultural appropriation, racial appropriation, and what it means to write about a particular experience that—if you haven’t had that experience—to approach it by adapting your own to fit that experience, kind of elides it in a fundamental way. And so, I think that if I were writing a nonfiction essay on the subject, the opinion that I would hold would be pretty clear. But by the time I put these characters in play, their own sensibilities shaped and resisted what I’d wanted to do. I think it’s a very—it’s always a fun moment, when you’re writing an “idea story” and one of your characters resists the idea. When a character refuses to say what you want her or him to say, then you’ve really created a character with contours, it seems to me. When the idea, as originally conceived, drops out of the story in question, that piece becomes almost like a donut—with a missing center. I feel like that’s what fiction is supposed to do, in a way. The really polemical Ayn-Rand stuff, the kind of writing that just pronounces itself and streamlines its characters all to serve a central thesis—that, to me, is the least interesting kind of novel. It’s a form of polemic, really.

And so avoiding that allows characters to speak from a different place?

And so avoiding that allows characters to speak from a different place?

I think if you’re somewhat skeptical about having strong ideological positions, like I usually am, you’re going to generally create characters that are going to resist. You’re going to make things complicated in terms of their thinking about the world.

I find the way religion comes up in your stories to be so interesting. On the one hand, your characters struggle at formal religion—they don’t know how to fill out the “Do You Believe in God?” question for online dating forms, or they spend all of Mass irritated by one old lady’s breathing. But at the same time, these guys are really wrestling with some big moral questions.

I just reread Gilead this summer, and that’s an amazing book to me because the narrative voice of that book is very much a devout believer, a Unitarian minister I believe, yet the book does not sound preachy or robotic. For me, to think about people grappling with issues of religion, I’d be hesitant about someone who’s too fixed in her or his point of view. I wouldn’t really be drawn to write about someone who is orthodox in any sort of intellectual way. A lot of the people I write about are skeptical about things in general, but still trying to establish some kind of belief system. I’ve probably just taught Hamlet too much—Hamlet is irreligious throughout the play and yet deeply consumed with religious questions.

There’s very little to me that’s more interesting than the history of religion or comparative studies of different religions. But the idea that you’re predetermined to think certain things because of a belief system, and that therefore your capacity to interrogate or question the world, the degree to which that is limited in terms of religious believe—that has always scared me. It’s not a coincidence, then, that I’ve had characters throughout all the books I’ve written who have had crises in faith and thought about these crises.

I’m thinking about The Thin Tear in the Fabric of Space and the story “St. Francis in Flint,” the young man who wants to write a novel and goes to the church all the time . . .

Yeah, he’s a good example. A lot of the first collection I wrote is comprised of stories I wrote right after my sister died. In the story of Edwin, his father has been killed in a plane crash. In the wake of his father’s death, Edwin is trying to reassemble his life and figure out what he believes in. Really he’s just overwhelmed with loneliness. And that definitely something I’ve thought a lot about.

It’s very hard, when someone you care about dies, to think about where they are, exactly. And the point of the title of that collection is to think about what the vacuity of space suggests to us. On the one hand, this is the place where so many theologians go to argue for the existence of God. How else could we exist in the mind-numbing vastness of space unless there was a designer who wants us to exist? But on the other hand, you focus on the blank space that surrounds us and the fact that we are suspended on this microscopic bit of dust over this vast vacuity—and it’s just freaky. It’s always terrified me.

As director of the Helen Zell Writers’ Program, you spend a lot of time talking with emerging writers about how to make a story work. I’m curious: when you sit down to do your own work, do you have those conversations running through your head, or is that something that you have to separate in some way?

No, it’s all connected. And sometimes a conversation I have with a student—and I try to make this clear with the student when this happens—sometimes that conversation is just an extension of a conversation I’ve been having with myself. It happens all the time.

But sometimes, really comically . . . I think it was about a year ago when I met with a student and tried to help her see how some of the sentences in one of her stories were kind of baggy and could be trimmed down, and literally that same afternoon I had a conversation with my editor and she did the exact same thing to me. And I just felt that that was a kind of wonderfully democratic indicator of this creative world we work in, where you’re trying to help someone but you’re also getting feedback.

What’s fascinating about what we do is how organic it is. Every individual project is establishing its own rules of engagement and its own needs. Everything we write is a different kind of plant that requires different amounts of sunlight, different amounts of water, and we’re all trying to figure it out together. I really like that. In the teaching context, if I were to find myself saying something that I couldn’t apply to my own experience as a writer, then that would feel inauthentic to me; I wouldn’t want to say it.

I see this in the feedback MFAs give to each other: collectively we are teaching ourselves as we give advice to one another. It’s a symbiotic thing. It’s really one of the great things about what we do. So much of what we do is so preliminary. If we imagine the old adage “show in a story, don’t tell” and then you read a great novel like 100 Years of Solitude that is mostly telling—every rule is meant to be broken. To see when those rules are broken and how effectively a story can work in those moments is really great. I don’t claim to know a formula for how to produce a great story and I wouldn’t want to know that, because it seems to me then you’d be imposing on students. The greatest criticism MFA programs get is that they produce similar kinds of writing. That’s always seemed to me to be the last thing we do, or the last thing that I would want to participate in. And I wouldn’t know how to do that anyway. What we do is far messier than chase after a single kind of story. We collaborate and build on our creative processes together, which is what makes our work truly communal and incredibly rewarding.