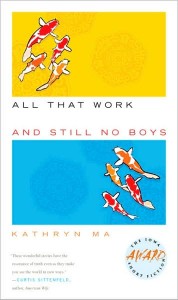

Kathryn Ma – photo by RayKo Photo Center/Michael Shindler

I met Kathryn Ma, winner of the 2009 Iowa Short Fiction Prize for All That Work and Still No Boys, for coffee at a café in San Francisco’s wired South Beach neighborhood, just a few blocks from the famed Writers Grotto where Ma is “an inhabitant,” as resident writers there are known. Ma, 53, was at once elegant and unassuming, with a wry sense of humor and a bold, infectious laugh.

I had read Ma’s slim collection of ten stories in one sitting; throughout, I was impressed by her complex portrayal of Asian American characters from all generations. Here were fierce, elderly Chinese American women wreaking havoc in the lives of their children; adults struggling (hopelessly) to control the tenacious traditions of their hired help; and children feeling helpless in the face of their parents’ racism. The subtlety and humor of Ma’s work feels new in the world of Asian American fiction, which I find often overwrought with ethnic detail. Yet her collection also affords that rare, warm feeling of familiarity that happens when a piece of art makes me feel more visible in the world.

A former lawyer, Ma answered my questions with thoughtful, measured responses that gave insight into her process. We discussed her nontraditional path to writing, her fascination with rage, and why the publishing world wasn’t ready for her book ten years ago.

The third of four children, Ma was raised in a suburban community outside of Philadelphia. Her parents – an engineer and a scientist who met in graduate school in Ohio – emigrated from China. Ma’s family moved to Southern California’s San Gabriel Valley, which she says was at that time a lonely place for a Chinese family, when she was in high school. Ma went to Stanford and studied history as an undergraduate and a Master’s student, completing a thesis on 19th-century women’s social history.

“I was interested in writing, but I didn’t have any vision; maybe I didn’t have the courage to think of myself as a writer,” Ma said. “Mostly, I was a reader. Books were incredibly important to me as a child, a teenager, in my 20s.”

“I was interested in writing, but I didn’t have any vision; maybe I didn’t have the courage to think of myself as a writer,” Ma said. “Mostly, I was a reader. Books were incredibly important to me as a child, a teenager, in my 20s.”

She considered doing a PhD in history, but realized that wasn’t her path. She found herself in law school, because she “didn’t have any better ideas,” she joked. Soon, she was practicing civil litigation law in San Francisco. This isn’t one of those stories about Ma hating a career that she was forced into. In fact, she explained that she enjoyed practicing law and was quite good at it. “But,” she said, “there was a tiny person inside of a person – a tiny voice – that kept speaking to me in some way about trying to write.”

Five or six years into practicing law, Ma was sitting in a library and, not very interested in the brief she was working on, she began writing a short story. She wrote it in one go and later shared it in a one-day workshop. This story got the attention of an editor at the New Yorker, who gave her good feedback but said they didn’t want to publish it.

“So, I thought, okay – end of story,” Ma said. “I went back to practicing law.”

After some time, the same the same New Yorker editor called Ma back and says they want to consider the story again, providing that Ma had done some revising.

“So, that panicked me!” Ma said. “I was in the middle of doing some enormous piece of litigation. I didn’t have any time to really work on it. I didn’t know what I was doing, I’d never taken a creative writing classes, I had no mentors. So, I fiddled around with it and sent it back. Then they wrote back again, after holding it for some time, and said: ‘Never mind!’” Again, Ma went back to practicing law.

“But it was just enough to tell me: I may have a narrative voice that I haven’t let out of the box,” Ma says. “I read a wonderful anonymous quote recently. It said: ‘The small voice inside of us makes up in accuracy what it lacks in volume.’ I thought, that is sort of what happened to me. I finally listened to some imperative in me to sit down and try to become a fiction writer.”

Ma admitted that the cultural expectations of her family probably played some part in why she hadn’t taken writing as seriously before, but “everyone has barriers,” she said, shrugging. “You either climb them or knock them down or let them stop us, and eventually I guess I was old enough. I had a family of my own – I began to understand that the choice was mine.”

Also, Ma said that she lost two very good friends within the space of a year – two young friends. “At that point, I said to myself: ‘What are you waiting for?’”

Having the discipline of working a 9-5 office job helped Ma transition into the life of a writer. After nearly 10 years of higher education and multiple degrees, she couldn’t bring herself to go into another classroom, so she eschewed the MFA path. Instead, she got a writing studio outside of her home and continued to leave the house in the morning to go “to work.”

“[My kids] had no idea that going to work meant going to this little dusty studio, sitting with my feet wrapped in a blanket and staring at my computer screen all day,” Ma said. “Having learned how to work in that kind of structure gave me enough discipline to beat my head against the desk.”

Ten years later, Ma had the ten stories of All that Work and Still No Boys.

Along the way, she found the most support through conferences like the Napa Valley Writers’ Conference and Breadloaf. “I was very wary of doing workshops or joining a writing group, because as a lawyer I had learned that writing by committee is always a mistake,” Ma said. “I wanted to learn my own narrative voice in my own ear.”

And what a gripping narrative voice that is. Ma’s title story contains many characters, but it focuses mainly on a triangle of three family members: Barbara, the eldest of five adult siblings; her mother, who needs a kidney transplant to survive; and Barbara’s youngest brother Lawrence, the only son of the family and the only match for his mother’s kidney. Ma manages, without judgment, to equally inhabit Barbara’s frustration with her mother for refusing Lawrence’s kidney and the mother’s own stubborn position.

“I wanted to find some dramatic, credible way that a modern Chinese mother who has brought her children up in a very westernized world – in an extreme moment – would finally show that deep bias toward her son,” Ma explained. “Because I think we carry these ancient cultural biases that we have with us and then generations that follow carry them with us, even though we work very hard to overcome them.”

The plight of Chinese American women isn’t itself a novel concept. Amy Tan’s work has tread almost solely in this arena, but Ma’s cadre of elderly Chinese women live ferociously in the present. Her book refuses to explain their stories with flashbacks to the Cultural Revolution–but these characters’ histories undeniably influence their actions. Ma said:

In our society, the elderly – and particularly elderly women – are invisible to us. They fascinate me. I think they have tremendous rage and tremendous pride. In many cases, a sort of fierce dignity that allows them to think of themselves as … as whole people. The rage interests me, because in many ways they are powerless but of course within an immediate family they are incredibly powerful.

Not all of Ma’s rage-filled characters are elderly. In her story “Second Child,” the main character, Daisy, is a young Chinese national who works as a tour guide for families who have adopted children from China and have returned to show their children their origins – specifically the orphanage where they were adopted from. Daisy’s rage comes from her own story: her sister was taken to one of these orphanages as a baby. Ma explained:

In some ways it is hard to write about anger. If you have a character that is full of simmering resentment, that character might come across on the page as just sort of sour or irritable. If you have a character who is constantly in a state of rage or heightened anger, that character is equally boring. In the title story and in “Second Child,” it is really about who the character is when anger has left them. Once anger lifts, evaporates – what does the writer create for the reader to see? That’s when the learning takes place for the reader and for the character.

Yet for all the rage that charges Ma’s stories, there is also an amazing sense of lightness that comes with an easy humor interspersed through the work. “Humor is the only antidote to anger. No one can tell an angry person to be unangry. Anger is like love. Anger doesn’t listen to any kind of rational explanation,” Ma said. “Humor is the first, best and last antidote to rage. It helps us survive a baffling world. I gravitate towards giving my poor angry characters something to lighten the psychological violence of their lives.”

When asked about the process for writing humor, Ma said it is all about soaking in the comedy of her friends and family – who she claims are hilarious. “I don’t strive for it. Striving just does nothing for the art. If you strive for anything on the page, it just falls apart in your hands.”

Ma’s book, with its unapologetically Asian American characters – who don’t do any cooking or talking to ghosts – was the first by an Asian American to win the Iowa Prize in the contest’s 40-year history.

“It’s not a surprise to me that it has taken me this long to get the collection published,” Ma admitted. “I think the kind of writing I do is more nuanced and more subtle than people were quite ready to grapple with twenty years ago, fifteen years ago, maybe even ten years ago. I wasn’t interesting in writing my parents stories, though I am always dealing with the echoes of that generation.”