When arranging his pick-up at the hotel, Jonathan Evison tells me to “look for the hat.” Initially, I think he might be joking, but the first thing I see in the lobby of the Marriott is a bobbing black hat moving through an adjacent lounge area. It circles around a column, comes up a half flight of stairs, and stops in front of me. Beneath it is the author of the book I’ve come to talk about. Wiry and self assured, Evison flashes a hustler’s smile that makes me wonder if I’m going to lose the title of my car to him before the night’s over.

When arranging his pick-up at the hotel, Jonathan Evison tells me to “look for the hat.” Initially, I think he might be joking, but the first thing I see in the lobby of the Marriott is a bobbing black hat moving through an adjacent lounge area. It circles around a column, comes up a half flight of stairs, and stops in front of me. Beneath it is the author of the book I’ve come to talk about. Wiry and self assured, Evison flashes a hustler’s smile that makes me wonder if I’m going to lose the title of my car to him before the night’s over.

“Whatever happens,” he grins, “let’s make it an early night. I’ve been out with friends every night this week, and I don’t think my body can handle another bender.”

“No problem,” I assure him. Evison’s rigorous tour has had him at twenty-three signing events in twenty-six days. Mornings have been reserved for print media and radio talk show interviews.

“Whatever you do, don’t even ask, because I don’t have any willpower, and I’ll do it. I’ll go,” he says. Immediately delighted by the subtextual invitation, I take the bait: “There’s a great little Irish-style pub downtown that has Tetley’s English Ale on tap and a locally produced rye that can’t be beat.”

“Oh, you sonofabitch,” he smiles. “Here we go again.”

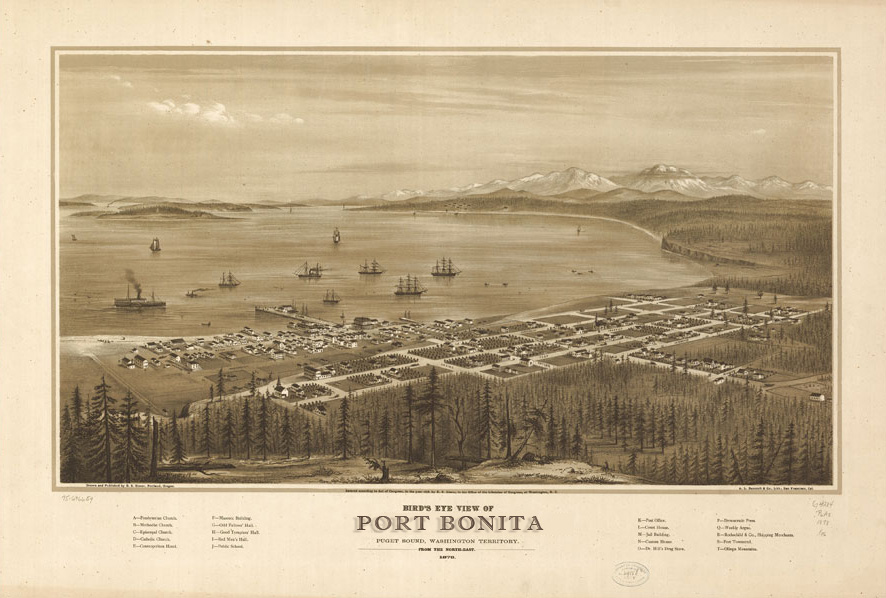

Over dinner, Evison pores over his book, trying to decide which pieces to read. This is no easy task. At five hundred pages, West of Here appears no different than any other novel—at first glance. What readers find, however, are two full casts of characters separated by over one hundred years of time: a nineteenth-cenury group of Washington state settlers and the modern-day population of precisely the same place. The former—a team of explorers, a journalist, an entrepreneur, an innkeeper, a prostitute—all dream of their individual and mutual futures as they strive to develop their rustic settlement, Port Bonita. The latter cast lives in the Port Bonita of 2006, and, mostly comprised of descendants of the nineteenth-century characters, can’t help but see, all around them, the decline of the community their ancestors struggled to establish.

Over dinner, Evison pores over his book, trying to decide which pieces to read. This is no easy task. At five hundred pages, West of Here appears no different than any other novel—at first glance. What readers find, however, are two full casts of characters separated by over one hundred years of time: a nineteenth-cenury group of Washington state settlers and the modern-day population of precisely the same place. The former—a team of explorers, a journalist, an entrepreneur, an innkeeper, a prostitute—all dream of their individual and mutual futures as they strive to develop their rustic settlement, Port Bonita. The latter cast lives in the Port Bonita of 2006, and, mostly comprised of descendants of the nineteenth-century characters, can’t help but see, all around them, the decline of the community their ancestors struggled to establish.

“It’s very sinewy,” Evison explains. “It’s been really hard for me to choose selections of the novel to read. Because everything’s so interconnected, I end up having to explain important contextual details. The problem is that, in doing so, I end up giving away things about the book that I don’t want to—things the reader should discover on his or her own.”

Charles Dickens

It’s easy to understand the challenge Evison faces. West of Here is populated by more than fifty characters, some of whom appear for the first time as the book comes to its close. Evison has read and enjoyed Dickens since he was very young, and although the Victorian author’s influence on the crafting of the characters and the scope of the events in the story is clear to the reader, the novel does not have the tidy resolution common to work of the period. This is not to say, however, that West of Here is by any means unkempt. Evison handles his robust cast with the steady hand of a master conductor, and the valley of time that lies between his nineteenth-century characters and their modern-day parallels creates just enough distance between them to accentuate the yearning that each has for the lifestyle of the other.

Emerson wrote that “there is a relation between the hours of our life and the centuries of time,” and elaborated, writing of man that “each new fact in his private experience flashes a light on what great bodies of men have done.” But he cautions his readers of what he calls “the defect of our too great nearness to ourselves.” Evison’s nineteenth-century characters are interested in “triumphs of will or of genius.” Their notion of self is contextualized by the vast ocean of history. The place that is West of Here might be the creation of a dam or the writing of an important exposé. It might be the mapping of the wilderness around Mount Olympus or the creation of an opera house. They all have their eyes on a future that is bigger, better, and brighter than their present.

Unfortunately, Evison suggests, we may have arrived at a point where we are experiencing this “too great nearness to ourselves.” His contemporary cast all find themselves more or less adrift. They are battered, broken, and bereft of any real notion of agency in the context of history. The place that lies West of Here, that numinous and attractive dream, has been replaced by a vague sense of insatiate hunger. Notions of greatness and fame have become indistinguishable, and the wide open space that was the future has become cluttered. The good news is that if Emerson is right, and man is “explicable by nothing less than all his history,” [emphasis mine] what we find in Jonathan Evison’s West of Here—expansive as it is—is only a few chapters of this history, and the dialogue that Evison is eager to open up, in this light, seems more important than ever.

Evison and I spoke about the book on and off that day, and into the evening, and have corresponded a little since then, finishing up our discussion. Try as I might, I wasn’t able to talk him out of drinks that evening, but we did manage to stay away from the rye.

Interview

Aaron Cance: A book this—you’ve called it sinewy—must take an extraordinary amount of focus to orchestrate. I imagine it was a real challenge to keep everything in hand.

Jonathan Evison: It’s almost maddening. It takes a great deal of “preproduction” thought. Then, when I finally do get to my work, I go in deep—really deep. It can be hours before I come up for air.

Do you work primarily from an outline, or do you let your characters drive the story?

I create characterizations and circumstances for those characterizations, but I let them make their own decisions. I try to stay as invisible as possible and let my characters do their work. I create a scaffolding that I can work from.

Port Bonita is a fictional place.

Right, but the history of Port Bonita in the novel is all based on the actual history of Port Angeles. I researched Port Angeles because it was such a perfect and interesting microcosm to work within. I actually found so much interesting historical information about this place, I had to leave a lot of it out. Then I fictionalized it and changed the name. I think they’re warming up the tar for me in Port Angeles right now. I have an upcoming tour date there.

When do you feel you’ve done enough research about a place to write about it? How much historical information is enough?

When do you feel you’ve done enough research about a place to write about it? How much historical information is enough?

I asked my friend David Liss—an incredible writer, if you haven’t read him, author of The Conspiracy of Paper, The Coffee Trader, and others—I asked him this very question. I said, “Dave, when do I stop researching and start writing?” He told me to stop when the research started to get in the way of the story.

This is actually the second novel that I’ve read in the last couple months that has had an unusually manipulated timeline (although all narrative timelines are manipulated to some extent). In West of Here, the reader finds a generation of characters settling Port Bonita during the late nineteenth century. One hundred or so pages later, you introduce a second cast of characters, all descendants of the first, living in the same geographical space in 2006. Why did you decide to structure the novel in this way?

I wanted to do everything I could do to get away from the wide-angle lens, and linear form, by which history is most often represented, in which stories are embedded. I like the idea of history as a conversation between the past and the present.

This is why you try to steer away from the term “historical novel?”

I conceptualized West of Here, and continue to think of it, as less of a historical novel and more of a novel about history itself.

Close to the beginning of the book, one of your main characters, James Mather, the explorer, tells Eva Lambert that he explores because he is interested in how the natural world humbles him. Are you also saying, through the unusually broad arc of the timeline, that people can also be humbled by time?

Yup. That’s pretty much the idea from page one.

The accomplishments that we can be so proud of are washed away by passing years.

The accomplishments that we can be so proud of are washed away by passing years.

Exactly. The place where this idea is most clear is when Krig makes his way back across the muddy fairgrounds and notices that the falling rain has already washed away his footprints.

Is there also the implication, here, that we are, perhaps, proud of the wrong type of accomplishments? That we pay little heed to the things that could make life really meaningful to us, and focus rather on things that seem to matter only in the present?

Yes. It’s definitely fair to say that implication is there. But then, all of history seems to be a great big tug-of-war between the past and the future, and it’s really hard to blame anybody for taking their eyes off the present, because so much of the present seems to deal with reconciling our past with our future. It’s sort of a cruel riddle.

Ethan Thornburgh defines his life by the dam that he orchestrates—it even distracts him from the child that he really never gets to know well—yet the reader sees that, only a couple generations later, the dam is going to be taken apart. Ethan’s descendant, Jared, is defined by his grandfather and father, and seems relatively unhappy on account of his inability to define himself.

Certainly. It has become harder and harder for people to define themselves in the modern world, as there seem to be fewer opportunities to do so. Also, those of us living in the modern world don’t have the luxury of short-sightedness, lest we all charge head-on to our own extinction.

The stakes are higher now than they’ve ever been before.

Absolutely.

Courtesy of the author

Tell me about the place that’s West of Here. It seems to me to represent far more than a geographical area. I read it as the wide open space of possibility, a place generated by, but not necessarily limited to, the imagination.

That’s the big fat question that sits in front of us. Where do we go from here? What modern idealism might lead us there? How do we avoid repeating mistakes we’ve made in the past?

These are the questions you’re bringing up with the book, through this dialogue between the past and the present.

Right. This is a search for a modern idealism—some parallel to the nineteenth-century Emersonian idealism found in the early portions of the novel. The book is meant to open that dialogue up. Every writing project should lead into dialogues that can be productive.

You mentioned during dinner that the discussion portion of your readings are what you most look forward to when you’re on the road.

This is the whole point: to get people to think—to talk about—the questions the novel raises.

Your characters are all seeking something. Some of them know exactly what they’re looking for and others don’t. The ones who don’t, mostly the contemporary characters, can only experience a vague, indefinable sense of longing that seems to be even harder for them to come to terms with.

Your characters are all seeking something. Some of them know exactly what they’re looking for and others don’t. The ones who don’t, mostly the contemporary characters, can only experience a vague, indefinable sense of longing that seems to be even harder for them to come to terms with.

Again, it’s really hard for modern folks to be imbued with a sense of personal destiny when so many opportunities have evaporated. Sadly, some vague idea of fame seems to have filled this gap.

It also seems to me that you’ve used the wide chronological arc to imply that we aren’t as well equipped today to venture “west” as people were in the nineteenth century. Some of the characters are emotionally stunted—Rita and Curtis come to mind. Timmon Tillman and Franklin Bell have been so softened by modern living that neither of them is prepared for the utter indifference of the natural world when they attempt to live in it.

Unfortunately, much of our physical and emotional stoicism seems to have evaporated with our opportunities.

Writing is a type of exploration, a journey that takes us into uncharted territory, allowing us a glimpse of what we might wish we were or showing us a life that can be more dramatic or exciting that our own. Are there any characters that you particularly identify with? Where is the place that’s West of Here for you?

Writing this book felt a lot to me like James Mather’s expedition—I locked myself in a room to work, I didn’t take phone calls, I wrote on the walls. The arc of the overall endeavor was a lot like James Mather’s expedition—tortuous during its execution until, like Mather, I found myself on the divide, the landscape rolling out ahead of me as far as I could see. At that point, it was exhilarating because I could see everything before me.

Was the most difficult thing about West of Here the transition from conceptualization to execution, then?

I love books that are ambitious. My very favorite books are the ones that can hardly contain their own invention.

Further Links and Resources

Jonathan Evison | WEST OF HERE from markmcknight on Vimeo.