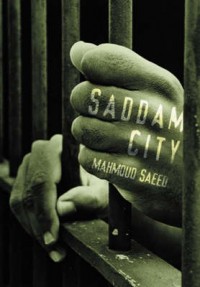

When my family and I moved from Beijing to Amman last summer (2010), I began to update my library of books by Middle Eastern writers. I read a memoir about dating in Saudi Arabia that reminded me of youthful novels by F. Scott Fitzgerald and China’s Chun Sue, an Egyptian epic that shared a kinship with Lawrence Durrell, and a collection of stories authored by a Palestinian full of the ghosts of Albert Camus and Paul Bowles. While these books balanced light and darkness, Iraqi writer Mahmoud Saeed’s novel I Was the One Who Saw (translated as Saddam City) was more emotionally challenging. Inspired by his experiences in Iraqi jails during the reign of Saddam Hussein, Saeed’s novel joins the list of works that detail the process by which humans survive imprisonment, deprivation and torture, works that include Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, Chol-hwan Kang’s The Aquariums of Pyongyang, and Elie Wiesel’s Night.

When my family and I moved from Beijing to Amman last summer (2010), I began to update my library of books by Middle Eastern writers. I read a memoir about dating in Saudi Arabia that reminded me of youthful novels by F. Scott Fitzgerald and China’s Chun Sue, an Egyptian epic that shared a kinship with Lawrence Durrell, and a collection of stories authored by a Palestinian full of the ghosts of Albert Camus and Paul Bowles. While these books balanced light and darkness, Iraqi writer Mahmoud Saeed’s novel I Was the One Who Saw (translated as Saddam City) was more emotionally challenging. Inspired by his experiences in Iraqi jails during the reign of Saddam Hussein, Saeed’s novel joins the list of works that detail the process by which humans survive imprisonment, deprivation and torture, works that include Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, Chol-hwan Kang’s The Aquariums of Pyongyang, and Elie Wiesel’s Night.

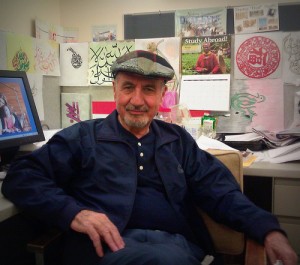

The following interview with Mr. Saeed, who currently teaches Arabic and Arabic Culture at DePaul University in Chicago, was conducted via telephone and email over the course of several weeks in March and April of 2011.

Interview:

Stephen Morison, Jr.: Could you describe where you are from in Iraq and tell us a little bit about your family background?

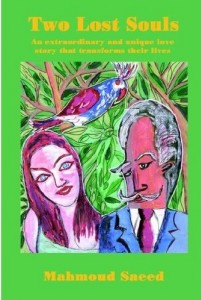

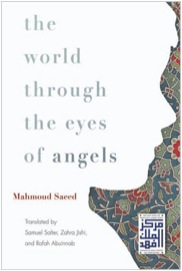

First of all, I would like to thank you for your interest in me, and I appreciate deeply the interest of Fiction Writers Review and its readers of contemporary novelists, poets and short story writers. This delights me. I wrote a novel about my childhood and my city environment. A novelist friend, Alan Salter translated it into English for me and it won the prize in translation at the University of Arkansas. This novel, entitled The World Through the Eyes of Angels, will be published by the University of Syracuse in the fall. I was born in the city of Mosul, one of the oldest cities in the world, which was built at the same time as the city of Nineveh. Arab writers accurately described Mosul more than 1300 years ago. These writings mention a market that partially remains to this day, and in which my father had a shop. Mosul’s population was comprised entirely of Arabs who practiced different religions such as Islam, Christianity and Judaism. In that time, all religions fraternized as one family, not like today, when everyone wants to kill everyone else. Living in the city depended on agriculture, so the city depended on rainfall. The city became very poor because the rains did not come every year, and when it did rain, it was not enough. In the summer when the harvest ended, people flocked to the city from the surrounding villages. These people included Kurds, Turkmen, Assyrians, Aramaic, Hebron, Shabacs, and Yezidis and they came to sell their crops and shop in the city.

First of all, I would like to thank you for your interest in me, and I appreciate deeply the interest of Fiction Writers Review and its readers of contemporary novelists, poets and short story writers. This delights me. I wrote a novel about my childhood and my city environment. A novelist friend, Alan Salter translated it into English for me and it won the prize in translation at the University of Arkansas. This novel, entitled The World Through the Eyes of Angels, will be published by the University of Syracuse in the fall. I was born in the city of Mosul, one of the oldest cities in the world, which was built at the same time as the city of Nineveh. Arab writers accurately described Mosul more than 1300 years ago. These writings mention a market that partially remains to this day, and in which my father had a shop. Mosul’s population was comprised entirely of Arabs who practiced different religions such as Islam, Christianity and Judaism. In that time, all religions fraternized as one family, not like today, when everyone wants to kill everyone else. Living in the city depended on agriculture, so the city depended on rainfall. The city became very poor because the rains did not come every year, and when it did rain, it was not enough. In the summer when the harvest ended, people flocked to the city from the surrounding villages. These people included Kurds, Turkmen, Assyrians, Aramaic, Hebron, Shabacs, and Yezidis and they came to sell their crops and shop in the city.

The climate in Mosul is divided into four seasons, each exactly three months. There is a cold winter in which temperatures drop to freezing. The spring is very beautiful and mild. Summer reaches ninety five degrees, followed by a temperate fall. Thus, Mosel is called “the mother of two springs.”

Our ancestors in Mosul engineered a plaster which was stronger than concrete. They used this plaster to build the highest minaret in the world in Mosul, more than nine centuries ago. Seven centuries after the minaret was built, it began to lean to the east, so severely that people thought that it would fall. The minaret has remained leaning this way for over two hundred years, thus the origin of Mosul’s nickname “The Humpback.” Mosul is also the only city in Iraq that used alabaster in its architecture. The city is also famous for its cuisine, including unique types of pickles, sweets and sausages.

Where were you educated?

I attended secondary school in Mosul, then the University of Baghdad, which was a very significant time in my life. I was such an avid reader that by the age of twelve I had read all the novels, collections of stories and history books in Mosul’s public library.

What writers were you exposed to as a young person?

Before completing high school I had read most of the authors whose work had been translated into Arabic including Cervantes, Dickens, Balzac, Flaubert, Stendhal, Hermann Hesse, Melville, Poe, Maupassant, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Gorky, Turgenev, Chekhov and others. In addition, I read the works of Arab writers including Naguib Mahfouz and Tewfik al-Hakim. I enjoyed reading modern translations as soon as they were published. I often read at least three hours a day, books by both Arab and non-Arab writers.

What motivated you to begin writing? When did you begin writing?

My writings were motivated by conflict in the world, the disparities between wealth and poverty, strength and weaknesses, oppressed people versus an arbitrary system of government, knowledge and ignorance, the old and the new, the constraints of customs and traditions versus liberation. I saw that conflict usually meant that those who are strong are victorious and those who are weak are defeated. I found that it was not always possible to speak your opinion frankly in life, at the risk of severe punishment. I found, however, that in the act of communicating by writing one can be free. If you are unable to resist evil in life, you can resist it through writing. Likewise, if you witness hunger and you cannot help the hungry, your pen can create a perfect world where people do not stay hungry.

Writing is an alternate world trying to solve the puzzle of man and his actions. One can attempt to answer questions through writing which seem intractable in life.

What most motivates me to write is the evil, brutality, and destruction inherent in the human spirit, questions about why we persecute each other, why we wish to control each other, why so many live lives of hunger, war, and injustice. All my writing is around solving this puzzle. This makes me feel weak, sometimes like I am nothing, because I feel that only politicians can answer these questions, not thinkers and philosophers. Politicians have an abundance of tools to help them make decisions and answer questions: money, power, agents, systems, and on and on.

What most motivates me to write is the evil, brutality, and destruction inherent in the human spirit, questions about why we persecute each other, why we wish to control each other, why so many live lives of hunger, war, and injustice. All my writing is around solving this puzzle. This makes me feel weak, sometimes like I am nothing, because I feel that only politicians can answer these questions, not thinkers and philosophers. Politicians have an abundance of tools to help them make decisions and answer questions: money, power, agents, systems, and on and on.

The second part of the question, when I started writing, is delicate. At first I was not familiar with writing essays; I wrote stories and novels only, but I wrote articles after that, I summarized or commented on them. I first began to write in school at the age of thirteen, when my teacher asked us to write about a new topic every week. The subjects were traditional, such as describing a village, a natural sight, specific weather, and I thought these topics boring, so I decided instead to write from my imagination. I would write stories or summaries of books that I had read before. This infuriated my teachers, and they punished me. This is why I failed in my Arabic class as a boy. I did not, however, fail other topics like arithmetic. I was faced with some fortunate circumstances during my last secondary school year when a talented poet named Shathel Taqa came to teach our Arabic class. He chose a topic and asked us to write about it, but I did not adhere to the topic, as usual. Instead I summed up the last novel I had read, and assumed I would be punished, as usual. To my surprise, he gave me the highest grade in the class and told me, don’t adhere to the topics that I give, write what you love. That was the starting point of my writing.

How do you define “success” as a writer? What were your first successes as a writer?

When I write any novel or short story, I feel like a man whose horse is participating in a race with lots of other horses. I always feel very concerned, and often I fear that my horse will fail or fall apart before it reaches the finish line. The comments of some critics make me feel at ease. I feel comfortable with my degree of success as a writer. Serious critics and avid readers lead to success, and it seems those are few in the Arab world. For example, if a writer occupies a senior position, or he oversees a magazine or newspaper, many critics will praise his work regardless of whether his work deserves it or not. In return, he will allow them to publish in his newspaper or magazine. My first success as a writer was winning a short story prize in Mosul when I was eighteen. The newspaper was called Fata al-Iraq.

What was it like to be a writer in Iraq when you began your career? Was there a government-sponsored writers’ union in Iraq? If so, what role did it play? Were you a member? How independent were writers permitted to be in Iraq?

It is a struggle to gain notoriety as an author in Iraq. In the Arab world, if you want to publish a book you have to pay for its publication, or contribute to it. There are few publishing houses that will publish a book at their own expense. Getting your work published in a magazine or newspaper depends greatly on your relationship with the editor or the owner of the magazine. In Iraq, for example, an author was only allowed to publish a book if he or she was affiliated with a government party. This was the case in the era of Saddam and after. I have not been allowed to publish anything in Iraq from 1957 until now. All of my books have been published outside of Iraq in countries such as Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, UAE, and Egypt. I submitted a novel in 1970 entitled Rue Ben Barka, however censorship prevented its publication. I finally published this novel in Egypt in 1984, then twice in Jordan, in 1992 and 1993. A friend of mine submitted my book in a contest at the Ministry of Information in Iraq, and after some months it won the first prize. When the authorities discovered it, however, the book was banned and they canceled the delivery of my prize. I had been prevented from publishing until recently. The Writers Union in Iraq had supported Saddam’s regime and now supports the new authorities.

It is a struggle to gain notoriety as an author in Iraq. In the Arab world, if you want to publish a book you have to pay for its publication, or contribute to it. There are few publishing houses that will publish a book at their own expense. Getting your work published in a magazine or newspaper depends greatly on your relationship with the editor or the owner of the magazine. In Iraq, for example, an author was only allowed to publish a book if he or she was affiliated with a government party. This was the case in the era of Saddam and after. I have not been allowed to publish anything in Iraq from 1957 until now. All of my books have been published outside of Iraq in countries such as Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, UAE, and Egypt. I submitted a novel in 1970 entitled Rue Ben Barka, however censorship prevented its publication. I finally published this novel in Egypt in 1984, then twice in Jordan, in 1992 and 1993. A friend of mine submitted my book in a contest at the Ministry of Information in Iraq, and after some months it won the first prize. When the authorities discovered it, however, the book was banned and they canceled the delivery of my prize. I had been prevented from publishing until recently. The Writers Union in Iraq had supported Saddam’s regime and now supports the new authorities.

How has the experience of being a writer in Iraq changed as you have grown older?

My experience has been very painful. The coup authorities destroyed two of my novels, one of which was published, the second of which was a manuscript. Both these novels were lost while I was imprisoned for one year and one day.

I also lost three novels because I was arrested or had run away for fear of arrest. Censorship has prevented all of my novels from being published in Iraq, so far. I must publish my work outside Iraq at my expense. The publishing cost is high, because I have never belonged to a political party in Iraq. The government has made it a point to distort my reputation, which puts me in a state of permanent hostility. What hurts me is my constant feeling that I am in a lasting state of siege, and I feel I will likely die with fear, and that destroys my nerves.

I also lost three novels because I was arrested or had run away for fear of arrest. Censorship has prevented all of my novels from being published in Iraq, so far. I must publish my work outside Iraq at my expense. The publishing cost is high, because I have never belonged to a political party in Iraq. The government has made it a point to distort my reputation, which puts me in a state of permanent hostility. What hurts me is my constant feeling that I am in a lasting state of siege, and I feel I will likely die with fear, and that destroys my nerves.

What caused at least two of your novels to be banned in Iraq?

As I said earlier, not two, but all of them. As I mentioned, I was not able to publish any fiction books or short story collections in Iraq, because I did not belong to the party regime. Since the year 2003, I have been prohibited from publishing in Iraq because I announced that I am against the death penalty, ransom killings, and the displacement of innocent people and the stealing of public money.

When and why did you leave Iraq?

I left Iraq in 1985. They wanted me to cooperate with them and forced me to sign papers stating that I would be put to death if I were to ever open my mouth to criticize the regime. I returned in 1991 after the first Gulf War. I was working in Dubai at the time and my work frequently required me to visit Iraq. The government began to harass me in 1994, so in 1995 I moved my family permanently to Dubai. I have not seen Iraq since.

What writers have influenced you in the past?

Books that have impacted me considerably include, A Thousand and One Nights and Tales of Arab Heritage Before Islam. These novels translated life and intellectual depth into Arabic. In my view, the novel is real life, not what we see in reality. Reality without human feeling is dead, but literature brings back life. Look at ancient myths; they turn creation stories into something similar to animals and imaginary objects of light, water, mud, spirit, and devils. Our long journey began with nothing and ended with rockets sailing around the universe.

Who are the other writers you most admire today?

I admire many novels. I think that there are many good novels, but no one writer wrote everything well. I think it is enough for a writer to have one or two good works. Some of the writers I admire include Naguib Mahfouz, Marquez, Kafka, Turgenev, Graham Greene, Herman Hesse, Mishima, Henry Miller, Dostoevsky, Philip Roth, Yasunari Kawabat, Jose Saramago, Mario Vargas Llosa, Hemingway and Steinbeck. I do not enjoy all of what they wrote; very great books are very few.

Can you describe your writing process? For example, when you wrote I Am the One Who Saw (Saddam City) did you begin with an outline? Did you utilize character sketches? Did you incorporate personal experiences or nonfiction stories? How long did it take you to write this book?

Yes, I created the outline or “skeletons” of the novel before I started, and then I wrote point by point. If I encountered an obstacle or difficulty, I stopped and worked on another story, since I’m always working on several novels at the same time. I began writing the novel Daughters of Jacob in the year 1973 and I completed it in 2006. I had been thinking of I Am the One Who Saw since the time when I was arrested, and I started writing it one week after they released me. So  as not to forget the details, I completed it in six months, but bad luck struck this novel when censorship in Syria deleted two perfect chapters. I didn’t consider it a healthy novel, it was sick, and when it was selected by Dr. Ahmad Sadri to be translated into English, I told him that this work of fiction is disabled and incomplete. I asked him to choose another of my stories, but he insisted. When the company changed the title I suffered a lot, because I had been inspired to choose the title that I did. I said to myself, it will fail completely, but the readers loved it in English and Arabic, which I didn’t expect.

as not to forget the details, I completed it in six months, but bad luck struck this novel when censorship in Syria deleted two perfect chapters. I didn’t consider it a healthy novel, it was sick, and when it was selected by Dr. Ahmad Sadri to be translated into English, I told him that this work of fiction is disabled and incomplete. I asked him to choose another of my stories, but he insisted. When the company changed the title I suffered a lot, because I had been inspired to choose the title that I did. I said to myself, it will fail completely, but the readers loved it in English and Arabic, which I didn’t expect.

What is your opinion of the current American involvement in Iraq?

Before the intervention in Iraq began in 2003, a reporter from Chicago’s Channel 11 said to me, “You are opposed to the regime of Saddam Hussein; no doubt you will support the U.S. intervention in Iraq.” I replied, “No. Intervention means warfare, and the war does not worry whether it kills innocents, children, the elderly, the sick or women.” Now you ask me the same question. I would like to tell you, I am a peaceful man, against violence, I want to see all the countries of the world abolish the death penalty, and the whole world live under a democratic system, with philosophers and intellectuals organized and elected by the people instead of corrupt politicians. A wounded child crying is a stab in the heart to everyone who creates war.

What do you think of the protests and uprisings that occur in the various countries of the Middle East today? What do you think the impact of these protests will have on the lives of writers in Iraq and the Middle East?

Perhaps the best news I saw and heard was that they changed the systems of Egypt and Tunisia in a peaceful manner, and this is what pleased me most, but unfortunately things went wrong in Libya. I hope that democracy prevails in Yemen, Algeria, Morocco, the Gulf States and Saudi Arabia, and I hope this also applies to Iraq, but I want from the bottom of my heart to change the situation in Syria, precisely because I know the suffering of the people there, I visited Syria more than twenty times. I described people, who are suffering there and the situation of prisons in my last novel, Ashshahena, or, The Truck, which was published in Cairo in late 2010. The torture of prisoners in Syria is worse than it was in Saddam Hussein’s era.

In your opinion, is it acceptable to speak of Iraqi literature as a national literature (distinct from Jordanian, Syrian and Saudi literature), or should Iraqi literature be taught and discussed as a part of Arabic literature as a whole?

I feel that the literature of each Arab country like Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon should be taught in public schools in all parts of the Arab world. They should be taught as Arabic literature, but they should say this poet is from Iraq, and this novelist is Egyptian, this is how they describe works from the region in all Arab magazines and newspapers. I did not read in the fifties or sixties the so-called literature of Iraq or Egypt, but critics in the seventies and eighties began chanting in newspapers, magazines, and undergraduate studies terms like: Literature of Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Iraq, etc… I think that this phenomenon will be reinforced. There is a similar condition to it, in the countries of Latin America. There is Columbia’s distinct literature, Mexico’s literature, and Cuba’s literature, regardless of the language.

How have the political movements and conflicts inside Iraq in the last fifty years affected Iraqi literature?

The political movements have affected literature in Iraq more than any other Arab country. In the forties and fifties literature was affected by left-wing movements: communism, socialism, peace movements, etc. Then it changed. After the sixties, the biggest political influence was the Baath Party, and a large portion of writers repeated what that the Baath government said. The Party would withhold enormous rewards—the equivalent to ten times their salaries—if they did not write what they were told to write. The writers who did not support the Baath party, like me, were prevented from publishing and stayed in the shadows so nobody knows them.

The political movements have affected literature in Iraq more than any other Arab country. In the forties and fifties literature was affected by left-wing movements: communism, socialism, peace movements, etc. Then it changed. After the sixties, the biggest political influence was the Baath Party, and a large portion of writers repeated what that the Baath government said. The Party would withhold enormous rewards—the equivalent to ten times their salaries—if they did not write what they were told to write. The writers who did not support the Baath party, like me, were prevented from publishing and stayed in the shadows so nobody knows them.

What projects are you currently working on?

I recently finished a novel about the bombing of cities during the Iran-Iraq war. At that time I was in Basra, and the Iranians bombarded Basra every day with dozens of bombs. Iraqis bombed Iranian cities in response. In both countries, civilians were falling dead, and the ones who didn’t die were suffering. Ahmad Sadri, the interpreter of my novel I Am the One Who Saw has read it and has told me he will translate it this summer. I am putting the finishing touches on another work of fiction that occurs in the sixties, which I wrote in 1991.

How do your students at DePaul University compare to the students you knew in Iraq?

Of course, they are different. Here students grew up with freedom and peace, so you see those good, spontaneous, light-hearted, honest, and non-complicated minds. I love them also for being outspoken and innocent. They adopt positions that are anti-war and anti-discrimination between religions and races, and this always pushes me to ask myself: Why did such torture happen at Abu Ghraib? And why do we see the killing of civilians in Iraq and Afghanistan?

The students in Iraq live under severe psychological pressure; they are afraid of death, threatened each moment, and so reluctant to express what they feel and afraid to show their opinions openly.

What are your hopes for your former students and friends back in Iraq?

The last time I was teaching in Iraq was in 1981. I had transferred to the main teaching department and was responsible for curriculum and official books. I had to oversee the development of writing of some of my ex-students. Some of them had become famous writers, but they unfortunately were Ba’athists. They had begun writing reports to Security about me and continued to attack me in print after I left Iraq. These attacks continued even until last year. In 2010, one of them attacked me in eight different articles in an Iraqi newspaper. My experience with them was so bad. They never invited me to any of the large number of literary festivals which have been held in Iraq since the sixties. Even now they behave this way because I refused to cooperate with the current Authorities.

The last time I was teaching in Iraq was in 1981. I had transferred to the main teaching department and was responsible for curriculum and official books. I had to oversee the development of writing of some of my ex-students. Some of them had become famous writers, but they unfortunately were Ba’athists. They had begun writing reports to Security about me and continued to attack me in print after I left Iraq. These attacks continued even until last year. In 2010, one of them attacked me in eight different articles in an Iraqi newspaper. My experience with them was so bad. They never invited me to any of the large number of literary festivals which have been held in Iraq since the sixties. Even now they behave this way because I refused to cooperate with the current Authorities.

What do you hope the future holds for Iraqi writers in the near term?

There will be no change in near term. Current politicians have imposed these classifications on Iraqi writers:

A – Literary collaborators with the former regime, who should be killed or prevented from publishing.

B – Writers who support the current ruling religious parties, and who enjoy tremendous wealth and are permitted to publish anything they’d like, no matter how trivial or superficial.

C – Writers who oppose both of the two regimes, who are mostly outside Iraq, like me.

To illustrate this reality, the writers who support the current ruling religious parties in Iraq issued a list of more than thousand writers who should be killed because they cooperated with Saddam’s regime. As a result of this, some were indeed killed, while others fled.

I have written several articles in Arabic newspapers published in London and websites that reject this bloody and dark trend, but my writing is used against me. My name has been added to other lists of writers who should be killed. Since the occupation began, I have wanted to visit Iraq one last time. However, I’m hesitant to go back there because of these lists. Literature in Iraq will not flourish unless it can be removed from beneath the power and the control of the regime. Even now, writers in Iraq depend on state aid to publish their work. They are poor, and cannot afford publishing’s costs inside Iraq or abroad.

Do you see the circumstances in Iraq changing in the next five years?

I am kind of optimistic, and I would love to see things improve in the future. It does not matter if it takes two years or two decades, but I want to see Iraq be rid of the influence of domination and the behavior of the religious parties and the criminal supervision of their militias.

I am kind of optimistic, and I would love to see things improve in the future. It does not matter if it takes two years or two decades, but I want to see Iraq be rid of the influence of domination and the behavior of the religious parties and the criminal supervision of their militias.

Religious parties have destroyed Iraq, they’ve looted its wealth and have led the country to the bottom of the corruption in the world. They have stolen by force a fortune of more than 500 billion dollars, while at the same time 42 percent of the Iraqi people live by picking through trash. Still, I have great faith that Iraqi literature can be on an equal level with literature in other countries after Iraq overcomes these criminals and their influence.

Further Links & Resources:

Banipal is an independent literary magazine publishing contemporary authors and poets from all over the Arab world in English translation, and was founded in 1998 by Margaret Obank and Iraqi author Samuel Shimon. The three issues a year present established and new Arab authors and poets in English for the first time through poems, short stories or excerpts from novels, and include author interviews, profiles and book reviews. Each issue is well illustrated with author photographs with the full colour covers featuring prominent Arab artists.

Banipal‘s latest—Issue 40—is devoted to Libyan fiction. Chock-full of short stories, novel excerpts, poetry and commentary, uncover the astonishing range of Arab literature through this wonderful project of translation.