Editor’s Note: For the first several months of 2022, we’ll be celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts.

In today’s feature, Carolyn Gan talks with Edwidge Danticat about Haiti Noir, a collection of stories Danticat edited around the time of the devastating 2010 Haitian earthquake. The interview was originally published on May 23, 2011.

Edwidge Danticat is a writer well known for her stirring and insightful stories about Haitian life. Her novels, including Breath, Eyes, Memory; The Farming of Bones; and The Dew Breaker, are praised as much for their cultural specificity as for their poetic universality. Critics call her Haiti’s literary voice, and Granta named her one of the Best Young American Novelists in 1996. She received a 2009 John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant, so one might even say that some have even called Danticat a genius. But no one would have pegged her for a noir writer until now.

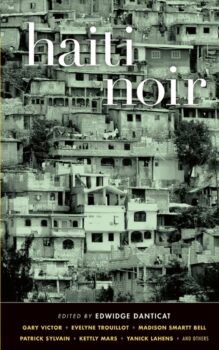

Though not commonly associated with genre fiction, Danticat was a natural choice to edit Haiti Noir, the most recent volume in Akashic Books’ groundbreaking series of original noir anthologies. The author speaks widely and often about Haiti, not only of the issues facing her countrymen abroad and at home, but also of her fellow Haitian writers. She includes many of these emerging and established authors in Haiti Noir. Moreover, it’s hard not to think of Danticat as a noir writer after reading her story “Claire of the Sea Light,” which is included in the anthology. Classic elements of noir—mystery, misfortune, even a graveyard—emerge masterfully from her powerful prose. “Claire of the Sea Light” is a remarkable story in a collection with many other extraordinarily nuanced tales.

Danticat was nearly done with editing the collection when, on January 12, 2010, Haiti suffered a devastating earthquake, an unimaginably destructive natural disaster that was followed by widespread suffering, flooding, and a cholera epidemic. At first, the editor worried that the stories would no longer seem relevant, but after adding three pieces about the earthquake, she found that Haiti Noir actually offered a unique portrait of the country before and after the disaster, snapshots of moments and places not often seen on the nightly news. What is more, the collection truly entertains; it is dark, surprising, and even funny. In the book’s introduction, Danticat confesses:

I can honestly say that, in spite of the difficult circumstances in Haiti right now, I have never felt a greater sense of joy working on any collective project than I have on this book . . . Each story is of course its own single treasure, but together they create a nuanced and complex view of Haiti and its neighborhoods and people.

The editor’s joy will certainly be shared by her collection’s readers.

In addition to being an acclaimed novelist and the editor of Haiti Noir, Edwidge Danticat is a prolific writer of short stories, published in more than twenty-five magazines and journals and collected in the National Book Award-nominated Krik? Krak!. She received the American Book Award for her novel The Farming of Bones, and her many other awards include a grant from the Lila Wallace Reader’s Digest Fund. Her moving memoir Brother, I’m Dying received the National Book Critics Circle Award. She has also written several books for children, including Eight Days: A Story of Haiti, which tells the story of a seven year-old boy trapped in rubble after the 2010 earthquake. Her recent essay collection, Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist at Work, is an extraordinary manifesto that will be appreciated by both immigrant and non-immigrant artists. Beyond her prolific work as a writer, Danticat has taught creative writing at both New York University and the University of Miami. She lives in Florida with her husband and children.

The following interview was conducted by email during May 2011.

Interview:

Carolyn Gan: How did you come to edit Haiti Noir?

Edwidge Danticat: Johnny Temple from Akashic Books called me one day and asked me if I would edit Haiti Noir for the publisher’s noir series. I was already a huge fan of the series, having read many of the books, so I jumped at the chance and said yes.

Haiti Noir features new stories by well-known, emerging, and even a couple of unexpected writers, including Mark Kurlansky. How were the stories collected? Were there authors or particular perspectives you sought out, or did the submissions shape the collection?

I’d like to think of the book as a kind of party. Most of the writers are Haitian and live in Haiti, but others are Haitian writers who live outside of Haiti, in Canada, Berlin, and the United States. We decided to also include two Haitiphile writers, Madison Smart Bell and Mark Kurlansky, who know Haiti well and have written about it extensively. The writers in the book range [in age] from early twenties to early seventies. There is a broad scope of experience represented. I did seek out some writers whose work I already know, and some other writers came to me via friends, particularly the younger writers. Marvin Victor, for example, was recommended by an older writer who had been his teacher. Now he has a hugely successful novel, Corps Mélés, that was published by a prestigious house in France. We got him just in time before he was huge, and he is going to be really huge among the next wave of Haitian writers.

I’d like to think of the book as a kind of party. Most of the writers are Haitian and live in Haiti, but others are Haitian writers who live outside of Haiti, in Canada, Berlin, and the United States. We decided to also include two Haitiphile writers, Madison Smart Bell and Mark Kurlansky, who know Haiti well and have written about it extensively. The writers in the book range [in age] from early twenties to early seventies. There is a broad scope of experience represented. I did seek out some writers whose work I already know, and some other writers came to me via friends, particularly the younger writers. Marvin Victor, for example, was recommended by an older writer who had been his teacher. Now he has a hugely successful novel, Corps Mélés, that was published by a prestigious house in France. We got him just in time before he was huge, and he is going to be really huge among the next wave of Haitian writers.

You say in the collection’s introduction that only a few of the included authors identify themselves as writers of noir. Your own work is not typically classified as such. Are you a reader of noir?

I am a reader of noir…not an obsessed one, but if I see a name I recognize, I go at it. The beauty of this series is that it brings new writers to noir, so it’s always fun to see what they come up with. I think people have said that my work is dark, which would be the literal definition of noir, but they might not call it noir. It was interesting to see, though, how much the writers wanted to jump in and try this. It was like having an assignment, coloring outside of the lines, for them.

Themes and images repeat throughout the collection. Unreliable electric generators, for example, buzz in the background and even appear as a plot point in Kelly Mars’s story. Magic winds its way through many stories as well, especially Marie Lily Cerat’s fantastic “Maloulou.” Are there aspects of Haitian culture that are inherently noir? Or that can be understood more clearly through the lens of the genre?

I guess there are aspects of Haitian culture that you might call noir or that lend themselves easily to the genre. The police investigations that are always ongoing and may never really be solved. The mystical elements of Haitian life, class difficulties, and conflicts. The writers, I think, made great use of those elements and more. In one of our earlier reviews, someone listed all the similar tropes, including Comme Il Faut cigarettes. It was interesting to see where many of the stories overlapped.

In Josaphat-Robert Large’s hair-raising story “Rosanna,” a particularly philosophical neighbor says that “[i]t’s almost impossible to discover what’s behind a mystery in [Haiti].” Do you agree?

Unfortunately that’s often true, especially in terms of solving crimes.

In April 2000, one of Haiti’s most famous radio journalists, Jean Dominique, was assassinated outside his radio station. At the time he was a friend of the president’s, yet his murder still remains unsolved. I guess one other way to say it is that it is very easy to bury a mystery under even more mystery in Haiti.

You include your mesmerizing story “Claire of the Sea Light” in the book. Was it written especially for the collection?

Thank you. It’s part of a longer book I am writing about how a child’s disappearance affects an entire small town in earth-shattering ways—earth-shattering in the sense that as the people of the town remember their last interaction with the child, they realize that they are all connected in more ways than they knew. It’s one of those tricky books, and it has a different ending than the story, but that story is the first chapter of that book.

“Claire of the Sea Light” is structured in reverse chronological order, which adds so much suspense. What inspired that choice?

I love playing with time in fiction. That’s somewhat noir inspired. Noir film inspired. I wanted to go back and forth in time but focus on one day, this girl’s birthday. Because her birthday started out so tragic—her mother dies in childbirth—she is never allowed to be happy. The entire plot of the book also happens in one day, in one night, really.

Do you always write fiction in English? How have your first two languages, Creole and French, affected your writing?

I moved to the United States when I was twelve. I speak French and Creole and write both, but I have always written creatively in English. It’s not even a commercial choice as people sometimes think. It’s just that when I got here and started writing, I started writing in English. If my family had moved to Spain around the same time, I would probably be writing in Spanish as one Haitian writer, Micheline Dusseck, does. Maybe English also offers a veil, some kind of distance that makes me bolder, but that’s just the way it’s always been. Always behind my English, though, are Creole and French certainly. I sometimes think I am doing simultaneous interpretation while writing: the characters are speaking Creole, and I am interpreting for them.

I’ve always admired that you never hinder the flow of your narrative with awkward translations. Somehow your translations enhance the rhythm. When do you know that a line in Creole or French is necessary?

When I use Creole and French it is easy, I think, to understand contextually. If you read carefully you should get what it means. However, I try not to do literal translations because I know a lot of people are reading the book who speak both languages, so I try to add a bit of extra nuance for them.

There is a heartbreaking moment in “Claire of the Sea Light” when the little girl sees a child’s tombstone near her mother’s and ponders “who the child was that her mother was now looking after in death.” It reminded me of Anne in your novel The Dew Breaker, who holds her breath when passing cemeteries because she imagines her drowned brother searching for his grave. Can you talk a bit about that intimate relationship between the living and the dead in your work?

It’s a morbid fascination for me, this fine line between the living and the dead. When I was little, my uncle was a minister and presided over a lot of funerals, so I often heard that death is not the end, and that there is something else, and that the dead are always with us. I believed this deeply and grew less afraid of the dead and less afraid of death. I was just telling a friend the other day—who is obsessed with past lives’ experiences—that my childhood made me totally unafraid of death because of all the post-death possibilities it provided. I only became afraid of death again, I think, when I had children. My only fear is of leaving them. Writing a story like “Claire of the Sea Light” is almost like getting those fears out of yourself, placing in someone else’s life a moment that personally terrifies you and then taking it out of your nightmares and putting it on the page.

You mention the idea of “leaving them”—that is, death as separation from your children. Of the father in “Claire of the Sea Light,” you write: “It took watching another child die in her mother’s arms to make him realize how very much he’d miss Claire when he finally gave her away for good.” Is separation just another kind of death?

Separation when you’re a little kid, I think, can feel like death, which is also something you are struggling to understand. In Haiti when people say someone is lòt bò dlo, they can mean that the person has died or that he or she has migrated, has gone to live in another country. After my first book was published, I met a woman who was five when her mother left Haiti for New York. She was asleep when her mother left, and no one had prepared her, so when she woke up and was told her that her mother was lòt bò dlo, she thought her mother had died. She was twelve when her mother sent for her. When she got to New York, her mother had changed, and she had changed, and she told me at nineteen years old that she never quite believed that her mother was really her mother. In her mind, her mother is dead, and she was tricked into an adoption of some kind. This is an extreme case, but it feeds my nightmares about parental separations when they are badly handled. Some families can be severed by that kind of separation forever, even when they are physically reunited.

In your recent essay collection Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist At Work, you wrote that “All artists, writers among them, have several stories—one might call them creation myths—that haunt and obsess them. [The historic public execution of revolutionaries Marcel Numa and Louis Drouin] is one of mine.” What are some of your other creation myths?

There are some new ones now, which I talk about in Brother, I’m Dying. My father’s death. That was and still is so painful. My uncle’s death, the death of my minister uncle who raised me. The birth of my daughters. Slowly I think your foundation myths change as your foundations shift under your feet.

You also write in Create Dangerously that “I used to fear [my parents and uncle] reading my books, worried about disappointing them.” When did you stop worrying about disappointing them? Did that worry extend to your larger Haitian audience?

Thankfully I worry after the writing is done, and the book is about to be published. While I am writing I give myself free rein. Yes, I used to worry about a larger Haitian or Haitian-American audience that they would recognize nothing of themselves in my work. But then I know, too, that we all have the stories we have, and those are the stories we tell by various means. It’s foolish to try to accommodate your story to any audience’s taste. The most important thing I can do as a writer is tell the truest story I know with the most love and passion and respect I possess. The rest will just have to take care of itself.

You’ve spoken and written widely about the situation in Haiti since the January 12th, 2010, earthquake, including conversations with NPR and articles for the New Yorker. Do your Haitian readers approach you to share their own stories?

They often do, but not forcefully. When I am in Haiti, I just observe. I don’t badger people for their stories. They go though enough of that. I just observe and live the moment I am living because, especially with family members, there are so few of them.

Could you talk a bit about your last visit to Haiti?

It was a private visit. Most of my visits are. There was still a lot of devastation. A lot of people without homes as another hurricane season is approaching. The visit before that I went with a group of women activists from an organization called We Advance that was co-founded by the actress Maria Bello. We visited one of the first women’s clinics in Cité Soleil, where they do rape recovery and counseling. Rape has become a very big problem in post-earthquake Haiti. We also met and broke bread with and sang and cried with some extraordinary women who had run for parliament at great risk to their lives. These women were just exceptional, some of the most amazing women I have ever met in my entire life.

Part of the profits from Haiti Noir will be donated to the Lambi Fund, a non-profit organization. Could you talk a bit about their work and why you selected Lambi?

The Lambi Fund works in the rural sector in Haiti, and they work with women, which was very appealing given as we often say that Haitian women are the poto mitan, the middle pillars of our society.

Haiti Noir was almost complete before the earthquake struck in January 2010. How did you select the three stories in the collection that reference the earthquake?

I thought we had to represent the earthquake somehow in the book so I asked a few folks if they had written some stories since the earthquake, and we got the three wonderful stories in the book. I think it’s really hard to write fiction so soon after a tragedy, but our writers did an amazing job, and I am really glad we made that choice.

Was the completion of the project part of your own healing process after the tragedy?

Those stories, as disturbing as they are, were indeed healing. I think a year, ten years from now, this is a book that you will be able to read and appreciate in terms of how it’s represented Haitian fiction in general and the post-earthquake moment in which the book was published.

Thank you so much for your work and for your time.

Further Links & Resources:

- Danticat writes about Haiti one-year-and-a-day after the January 2010 earthquake in the New Yorker: “A Year and a Day.”

- As part of NPR’s Arts & Life series, the author reads from her children’s book Eight Days: A Story of Haiti on Morning Edition. Listen here.