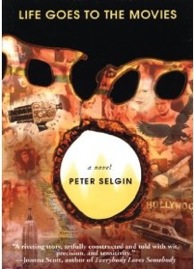

For Peter Selgin, a story best moves its reader if it incorporates as much from real life as it does from the author’s imagination. By synthesizing veracity with fiction, he composed his novel Life Goes to the Movies. The book bills itself as “a love story between two straight men.” Dwaine, a Vietnam veteran turned aspiring filmmaker, takes under his wing Nigel, an Italian-American in search of a more authentic American identity. Together they are sucked into the analogous vortices of movies and madness.

Selgin, an Italian-American like Nigel, based much of the story on his experiences in New York. The result is a deeply personal narrative, but one that is ultimately unique to the protagonist and not Selgin. Still, for readers, the story is as captivating as it is believable. As Margot Livesey, author of The House on Fortune Street, says, “Selgin’s vivid account of New York in the 1970s, his richly complex characters, his encyclopedic knowledge of film, and his sense of how small the gap is between good luck and bad make this an utterly absorbing novel.”

Before being published by Dzanc Books in 2009, the novel was twice a finalist for the James Jones First Novel Fellowship, and took second place in the AWP Award for the Novel. Selgin’s first book, Drowning Lessons, a collection of short stories, won the Flannery O’Connor Award for Fiction in 2008 and was published by The University of Georgia Press that same year. His books on writing, By Cunning and Craft and 179 Ways to Save a Novel, were published by Writers Digest Books in 2006 and 2010, respectively. His non-fiction has also been collected in Best American Essays.

Before being published by Dzanc Books in 2009, the novel was twice a finalist for the James Jones First Novel Fellowship, and took second place in the AWP Award for the Novel. Selgin’s first book, Drowning Lessons, a collection of short stories, won the Flannery O’Connor Award for Fiction in 2008 and was published by The University of Georgia Press that same year. His books on writing, By Cunning and Craft and 179 Ways to Save a Novel, were published by Writers Digest Books in 2006 and 2010, respectively. His non-fiction has also been collected in Best American Essays.

While fulfilling his appointment as Georgia College & State University’s visiting writer-in-residence, Selgin has been hard at work on a new novel, Hattertown. This novel, too, blends truth and fiction, but with a broader perspective that includes not merely personal but regional and cultural history. As one of Selgin’s students, I was able to ask him a few questions about his strategy for fictionalizing truth, and also on issues related to teaching creative writing. Following the interview is an excerpt from Hattertown.

Interview:

JT Torres: Life Goes to the Movies is heavily autobiographical, and yet it is ultimately a novel and not a memoir. Can you talk a bit about the process writing it?

Peter Selgin: Life Goes to the Movies is essentially the novel I’m always telling my students not to write—a work that is almost entirely autobiographical and blurs the line between fiction and memoir. The novel grew out of a series of journals that I kept during the period in which I “lived” its material. This is often the case with first novels, though Life Goes to the Movies is not a first novel; I had written two other novels before it. But the material haunted me, and against all better judgments—including my own—I stuck with it through a process that wound up taking fifteen years.

Peter Selgin: Life Goes to the Movies is essentially the novel I’m always telling my students not to write—a work that is almost entirely autobiographical and blurs the line between fiction and memoir. The novel grew out of a series of journals that I kept during the period in which I “lived” its material. This is often the case with first novels, though Life Goes to the Movies is not a first novel; I had written two other novels before it. But the material haunted me, and against all better judgments—including my own—I stuck with it through a process that wound up taking fifteen years.

Giving artistic shape and integrity to real life isn’t so easy. It reminds me of a game I used to play with my father called “The Five Line Game.” I’d draw five random lines on a piece of paper, and he’d have to turn them into a picture of something. In writing Life Goes to the Movies, instead of five lines I had these true episodes and real people from a certain period in my life.

In terms of fictionalizing, little was done beyond telescoping events and making a love-triangle central to the story. But most of the effort was put into making each section or chapter of the book relate to a certain type of movie: war, western, pornography, etc. In this way “Life” turns into art.

Yet The Florida Review published “Eagle Electric” as nonfiction, despite the fact that the passage is an excerpt from Life Goes to the Movies. Where do you personally draw the line between fact and fiction?

With that book I really didn’t. I would have published the thing as a memoir, but too much shaping had been done—too many poetic liberties, too much “art.” And beyond that there were issues of privacy and the potential for libel. I feel I should add, by the way, that I don’t take the opposite view—that a work of fiction can or ever should be passed off as nonfiction. With fiction, you’re free to invent, but you’re also free to use facts and tell the truth; you can hardly avoid doing so. But with nonfiction you swear to tell the truth, mainly.

What do you mean by “mainly?” Where do you feel it’s ok for nonfiction writers to not tell the truth?

First of all, any genre that claims a monopoly on “the truth” isn’t being exactly—well, truthful. Poetry may come the closest, since it deals in feelings and so its subjectivity is not only a given but forms the substance of its truth. Memoirists all lie—unintentionally, of course, for they simply can’t help not lying no matter how hard they try. In fact, the more they insist on being truthful the more they flagrantly lie, passing into the far more egregious sin of dishonesty.

What’s different about nonfiction is not the result but the intent, which is to try and get at the truth, however impossible. Therefore, when I say that the nonfiction writer swears to tell the truth “mainly,” I mean to the best of his—and his memory’s—ability (which, unless he’s kept extremely detailed on-the-spot records, will be extremely limited).

The truth your stories seem to seek is the truth of identity: the constructs that define us as individuals. The search for a true identity is also exemplified in your biography. Your birth notice gave your name as “Selgin boy B.” Before that, your father had changed his original surname, “Senegaglia,” to “Selgin.” You say he was proud to use a name that people could pronounce: “Like Elgin, the watch—but with an ‘S.’” It seems America is comprised of indefinite identities. How have you worked such ambiguities into Nigel and Dwaine? Dwaine, for instance, also has a surname that is questionably spelled and pronounced.

Actually it’s Dwaine’s Christian name that can be spelled many ways. It comes from the Gaelic “Dubhn,” meaning “little” or “dark” or “mysterious,” or some combination of those things. I think names are terribly important much as titles are; they tell us about the characters they stand for just as our titles point to the hearts of our stories, or should. But I’m also very interested in identity—perhaps because I’m a son of immigrants who happened never to belong to a community of immigrants. If my parents had any clear identity it was as a pair of sore thumbs standing in that small, rural town where I grew up. This put me in an odd position. On the one hand I was an American—that is, I was born in the USA. On the other hand I had these eccentric parents from Italy. I was also my father’s son—the son of a highly egocentric, deeply eccentric man, an atheist and a genius whose IQ was apparently off the charts. While in some ways I relished the uniqueness conferred by all this, I also envied those who could point to a larger identity and say, “I am this” or “I am that,” and have people understand right away what they meant.

But yes, my characters are all “orphaned” in terms of identity. They don’t represent any group or nation or even their own genders, especially. In this sense, they are alone and lost and searching for other lost souls with whom to identify. Hence, the magnetic attraction of Nigel, the displaced immigrant child, to Dwaine, the psychotic V-Vet, and vice-versa.

Does your particular interest in identity have anything to do with the fact that you are not only left-handed but a twin? Both these issues are braided together in your wonderful essay “Confessions of a Left-Handed Man,” which was anthologized in Best American Essays 2006. I wonder if you could talk about “difference” a bit more.

I believe we are each minorities, that is, those of us who are sensitive enough to be at all aware of our uniqueness. And all minorities are persecuted—if only by themselves. The Inquisitor asks not “Do you believe in God?” but “Am I normal? Do I belong?” Being a twin is a paradox. On the one hand you’re automatically a member of a tribe of two; on the other, you’re something of a freak. Until we were seventeen, George and I fought like hell. We were two mirrors trying to smash each other. It wasn’t fun. On one hand (again, paradoxically), each of us wanted to be unique; on the other we didn’t want to be part of this little circus sideshow known as The Selgin Twins. And yet our fights were the attraction that drew a crowd.

As for being left-handed, for the most part I embraced it as something that set me apart from my brother. It was my much desired mark of distinction.

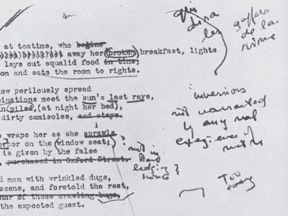

Let’s switch gears and talk about your pedagogy for creative writing. Arguably one of the hardest skills for students to master is that of revision: the struggle to approach our own work with an objective eye, which we often lose. How do you teach revision? Also, can you discuss the process of revision and what you do to read something you wrote as objectively as a cynical editor would read it?

I have written about this in my books, By Cunning and Craft and 179 Ways to Save a Novel. The key to revision is time, which gives us distance to our material. However, life doesn’t always provide us with lots of time. I find a lot of students try to write in a rush. Ideally, every work of art should be put away for a year or two and revisited. But that’s a luxury most of us can’t afford; in fact, now that we have computers, we revise things more often and immediately, forfeiting the objectivity that comes when you allow work to ripen.

In my own process I’ve been known to revise sections from my work up to twenty times. I don’t mean tweaking; I mean totally reworking. But then it gets down to where I’ll retype a whole section of a book or a story a half-dozen times, changing only a few words and phrases here and there, just to get the rhythm right, to get all the words to mesh together perfectly—or what seems like perfection at the time. I tend to do this until the words “set” like a gelatin mold, until it seems that they are frozen into place, that no more revision is possible. Then it’s “done.” I’m a great believer in revision. It’s the part of the writing process I most enjoy.

How so? What is most enjoyable or satisfying about the revision process?

Well, with revision you’re presumably in the home stretch, and you have the satisfaction of knowing—or believing—that the latest revision just may be the last: a vain hope in my case, usually. But I also relish the process of fine-tuning, of sweeping away every last bit of sand and sawdust, filing down the mold edges, making every sentence ring like a bell.

I think of Gene Fowler’s quote: “Writing is easy, all you have to do is stare at a blank piece of paper until drops of blood form on your forehead.”

And revising something already written beats staring down a blank page any day.

One way I’ve learned to generate distance between myself and my work is to step away from it and read a novel that either accomplishes what I’m trying to accomplish or does something drastically different. Now, from my days as your student, I remember your warning: Don’t just read the same authors every student in every MFA program reads, but try to discover new voices. What are some authors you recommend of which students may not know?

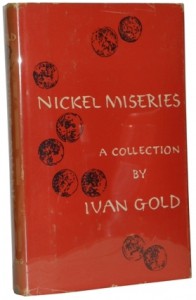

I’ll drop some names here and see if you know them. Alexander Trocchi? Emmanuel Bove? Ivan Gold? Trocchi was a Scottish novelist and heroin addict whose artistic life was so consumed by his addiction that the only way a publisher could get a novel out of him was to supply his habit. He was given a certain amount of money per page of output. In this way, Cain’s Book, Trocchi’s best novel, was written. Really, it’s more of an anti-novel by a novelist who refuses any form of work including that required to produce a novel. Bove wrote several novels during and after World War II; but the first, My Friend, is the most important in that it showcases Bove’s chief characteristic, his eye for the telling detail. Ivan Gold’s Nickel Miseries is one of the best short story collections I’ve ever read or expect to read. I discovered it on a dusty shelf in a used book store. I’d never heard of him. That’s what I do: I go into libraries and used book stores and scrounge, reading passages pretty much at random, until something catches my eye. My enthusiasm for “discovering” Gold was shared by Lionel Trilling, who thirty years prior to my finding Nickel Miseries on that dusty shelf predicted that Gold would be one of the towering writers of his era. Gold’s drinking unfortunately put the kibosh on that.

I’ll drop some names here and see if you know them. Alexander Trocchi? Emmanuel Bove? Ivan Gold? Trocchi was a Scottish novelist and heroin addict whose artistic life was so consumed by his addiction that the only way a publisher could get a novel out of him was to supply his habit. He was given a certain amount of money per page of output. In this way, Cain’s Book, Trocchi’s best novel, was written. Really, it’s more of an anti-novel by a novelist who refuses any form of work including that required to produce a novel. Bove wrote several novels during and after World War II; but the first, My Friend, is the most important in that it showcases Bove’s chief characteristic, his eye for the telling detail. Ivan Gold’s Nickel Miseries is one of the best short story collections I’ve ever read or expect to read. I discovered it on a dusty shelf in a used book store. I’d never heard of him. That’s what I do: I go into libraries and used book stores and scrounge, reading passages pretty much at random, until something catches my eye. My enthusiasm for “discovering” Gold was shared by Lionel Trilling, who thirty years prior to my finding Nickel Miseries on that dusty shelf predicted that Gold would be one of the towering writers of his era. Gold’s drinking unfortunately put the kibosh on that.

What MFA programs sorely need to do is steer students away from the usual suspects; we know too well who they are. As for bestsellers, as both a teacher and a reader, I go out of my way to avoid them. Not that bestsellers are necessarily bad, but they get enough attention, and there’s the danger of everyone drinking from the same well. Better to go around with a parched throat until you find a fresh spring.

But isn’t it also important for writers to share a foundation of work? Shouldn’t there be a common point of reference? Not reading bestsellers, per se, but those writers who have shaped 20th century literature.

Gustave Flaubert

I suppose. But who gets to decide who those writers are? The assumption is that literature is one long conversation taking place between authors living and dead, with the living writers all responding and presumably adding something relevant and new to the discourse. But literature isn’t a conversation. It’s more like a house of many rooms and more than a few attics and dungeons, all occupied by people scribbling away, some by writers who, though dimly aware of the other rooms, never leave their own. Flaubert’s peers were constantly on his case for living away from Paris, out in the sticks with his mother. They felt he was out of touch. Flaubert lacked that common point of reference you refer to, which back then was called Paris. A good thing, since otherwise we might not have Madame Bovary.

Staying—approximately—on topic with the “anxiety of influence,” were there any books you used as a model for your current novel-in-progress, Hattertown, in which you employ a narrator who looks back several years over the course of the novel’s narrative frame? What authors, if any, do you admire for their ability to handle this sort of retrospective narration?

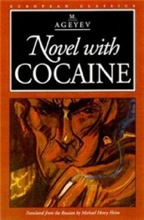

I was very taken with John Updike’s early novel The Centaur, in which he renders, very effectively in my opinion, the psyche of Peter, his sixteen year-old protagonist, through a narrator who is that same protagonist looking back on his youth. The retrospective telling allows Updike to pitch his voice to the rafters, something no 16-year-old narrator could do. It also allows for great and charming perspective. Similarly, I was taken with Novel With Cocaine, a pre-revolutionary Russian Catcher in the Rye whose author’s identity remains a mystery.

I was very taken with John Updike’s early novel The Centaur, in which he renders, very effectively in my opinion, the psyche of Peter, his sixteen year-old protagonist, through a narrator who is that same protagonist looking back on his youth. The retrospective telling allows Updike to pitch his voice to the rafters, something no 16-year-old narrator could do. It also allows for great and charming perspective. Similarly, I was taken with Novel With Cocaine, a pre-revolutionary Russian Catcher in the Rye whose author’s identity remains a mystery.

Leo, the narrator of Hattertown, ultimately looks back fifty-two years to tell the story. Tell us a bit about how you found Leo’s voice. Does he look back on the story with guilt, regret, or nostalgia? Presumably, the structure of the novel means you’re working with two Leo’s—a thirteen-year-old Leo and a wiser sixty-five-year-old Leo—bound by the same voice. What were the challenges?

This issue comes up a lot in workshop: how to reconcile the voice of a young character with that of the adult narrator looking back over decades. The solution, one solution, is to set the terms early. If you’re going to allow your narrator freedom of diction—letting him or her speak as decorously or poetically as possible, using highly evolved diction—you need to establish that voice early, and then filter everything through that sensibility. Then when the scenes takes place in which the narrator is, say, twelve years old, we see those scenes through this sepia-toned, nostalgic filter in such a way that we’re never totally removed from the sensibility of the adult looking back.

Now, this has drawbacks: it can detract from the immediacy and authenticity of the youthful scenes. But if done carefully, working from within character and situation, during those moments of deep immersion in the psyche of the young character the diction will relax; reflection falls away and with it all diction inappropriate to the sensibilities of the young character. The goal isn’t to allow childish or simplistic diction, but a sort of neutral diction that doesn’t wrest the reader out of the milieu.

Hattertown focuses on the relationship between two very disparate male characters—Leo Napoli and Jack Thompson—each with suppressed secrets. It’s a familiar theme in your work. What about odd friendships interest you so they reoccur in your writing?

My characters are essentially loners. Loneliness is its own nationality, its own country, gender, ethnic group. I’m also very interested in non-traditional or “odd” relationships. If one of fiction’s highest aims is to arouse in a reader a heretofore unknown or unfamiliar emotional response, what better way to go about doing so than with an “odd” relationship—one where the standard bindings of marriage, family, or sexual intimacy are subverted or distorted. What about two men (or women) who are in love but are not homosexual? What about a boy and an older man? Obviously some of these categories are dangerous: all the better.

This seems to be another side of that same familiar theme—non-sexual friendships between individuals of the same gender. Why should that be “odd” or “dangerous”? Can you talk more about this idea?

A friendship can be erotically charged without the eroticism giving way to sex. I might not even give way to sexual desire, only to an attraction that goes beyond oblivion or innocence. Those are dangerous relationships because they’re so highly charged. I once was told the story of a father who encouraged his daughter to marry a man because he, the father, was in love with the man: not sexually, but in every other way. When in the course of the marriage his daughter complained that she felt no love for this person, nor any love from him, the father said, in a few words, “Don’t worry; you’ll get used to it. It’s not all that important.” The consequences were not only dangerous for all parties concerned, but tragic. This sort of thing interests me far more than conventional “love” stories. We just don’t have enough categories to encompass the full range of potential erotic dynamics between people. This lack of sufficient categories may in itself be a cause of danger.

Your characters often find themselves consumed by passions beyond “love,” as in Leo’s stepfather’s obsession with hats, illustrated in the following excerpt from Hattertown. Can you give an introduction? Why not select an excerpt showing Leo and Jack’s relationship? Does Leo learn something from his stepfather’s assiduity—trying to win President Kennedy as a customer?

I considered serving up a scene between Leo and Jack, but that relationship is much harder to convey in a short except. And anyway I’m especially fond of the “hat” theme in the book and the symbolism of hats as expressed through Leo’s stepfather—what almost amounts to an obsession. Mr. Waple equates hats with civilization, with a “uniform” code of human behavior that should never be broken but which is also under severe threat. If you know that the novel takes place in 1963, only a year or two before morals burst open under pressure from the protest movement and women’s lib, then you’ll appreciate the analogy and its place in the book as a whole, and as a way to underscore Leo’s friendship with the recluse Jack, who lives entirely against the norms of society. Jack is the antithesis of Leo’s stepfather. As it turns out, both men have something valid to offer: civilization and rebellion depend on each other. But that realization comes very late in the novel.

Anything else you’d like to tell the reader about this excerpt from Hattertown?

I think it’s self-contained. The quoted letter, by the way, bears similarity to an historical document. That’s all I’ll say.

from Hattertown:

But the real purpose of helping my stepfather at his store was to please my mother. “It will cheer him up,” she said to me. “You know how much he enjoys your company, Leo.” Not that my stepfather needed cheering up; Walter J. Waple, Jr. was nothing if not a resolutely cheerful person, this in spite of the fact that his store was failing badly and had been for some time.

It wasn’t just my stepfather’s store that was failing. All over the country sales of men’s hats were down, and had been in decline for decades, with the steepest decline beginning just after World War II. Some blamed the war itself: the last thing returning soldiers wanted was to wear anything on their heads, having come to equate headgear with subjugation. Others blamed the new models of automobiles, with their low-slung roofs that rendered the public tipping of hats invisible if not impossible. Still others blamed the era of air travel, which put luggage space at a premium, forcing men to keep their hats in their laps or see them crushed under suitcases. Meanwhile clubs and restaurants had taken to charging patrons for what had once been a common courtesy: checking their hats. And then there were those “scientific” studies suggesting that wearing hats promoted baldness in men—studies that, in my stepfather’s opinion, had “absolutely no merit whatsoever. In fact,” he insisted, “it’s been proven beyond a shadow of a doubt that wearing a hat is good for the scalp. It protects the follicles from humidity, dust, and dirt—not to mention the sun’s damaging rays! Upon my word, the worst thing a man can do to his head is expose it to direct sunlight, if you will.”

*

Still, until as late as 1960 Waple Hats had done a brisk trade, but then even his store began to fail. For this my stepfather blamed neither wars nor jet travel, but a combination of shoddy salesmanship and an impressionable public subject to whims and fancies of less-than-worthy role models.

With respect to the latter, the man my stepfather held most to blame for leading the fickle public astray was our 35th President, John Fitzgerald Kennedy — known disparagingly to my stepfather and others in the hatter’s trade as “Hatless Jack.” At the mere mention of Kennedy’s name my otherwise even-tempered stepfather’s lower lip would curl into a sneer, and the generally equable blood in his veins would turn to gall. For Walter J. Waple, Jr. hated President Kennedy’s guts, and had since the frosty afternoon when he took the oath of office, the first President ever to do so without (to quote my stepfather) “so much as a beanie on his handsome, hairy, Irish Catholic head.”

*

Yet even for this gross act of indecency my stepfather had been prepared to forgive our new President. After all, Kennedy was young, and subject to a young man’s lapses in taste and judgment.

And in Kennedy’s defense it should also be said that on that blustery, bitter-cold day in January 1961 Eisenhower likewise went hatless, as did Vice President Johnson, and Mr. Robert Frost—our hoary, frail Poet Laureate, his thin hair flying like a white kite in the breeze, his ancient eyes so dazzled by the brimless winter glare he couldn’t read the words of his own inaugural poem (which calamity, my stepfather could not resist pointing out to anyone who’d listen, would have been avoided had he worn his hat[1]).

Still, for the President-elect to appear hatless at his own swearing-in ceremony ¼ Upon my stepfather’s word, it was more than uncouth: it was, as it were, unforgivable.

*

Even so, even so, my stepfather had been willing to give the new President another chance. To which end Walter J. Waple, Jr. did something he’d never done before: he reached out to a Democrat. He wrote the newly elected President a letter. He typed it himself on the Royal standard that he kept in the office at his store, on stationary bearing the store’s logo—a top hat crossed by a cane and gloves. He made two carbons, one of which I quote from:

Dear Mr. President,

I was sorry to read that you had a cold and hope you recover quickly and completely. The same paper that reported the story also carried a picture of you wearing a hat and coat, and said you donned them because of your cold.

As the owner of the oldest hat retail store in Hattertown, Connecticut, I was naturally pleased to come upon this photograph of you wearing a hat. However, I must express to you my very strong conviction that there are other, perhaps even more significant reasons for wearing a hat other than as protection against the elements, for not only does wearing a hat flatter your already handsome appearance, but if I may be so bold as to say so, it gives you an air of maturity, authority, and dignity in keeping with your office. If that is not reason enough, might I point out that there are approximately 25,000 working men and women in the hatting industry who stand to benefit from your wearing a hat—and again, Mr. President, not merely as a protective covering, or something strictly utilitarian (though to be sure a hat fulfils those functions as well), nor as a fashion statement, but, if I may be so bold, as something far more important: as a symbol of honor and pride.

And now may I take this liberty, dear Mr. President, to offer you my services as haberdasher and owner of Waple Hats, to come to Washington personally and prepare a hat wardrobe for you? It would be a great privilege for me, and you may rest assured that, if you are accepting of my proposal, that under no circumstances would myself or anyone in my knowledge take advantage of this service for purposes of publicity.

Respectfully Yours,

Walter J. Waple, Jr.

Chief Executive Officer and Sole Proprietor

Waple Hats, Incorporated

To his very fine letter my stepfather never received a response, and for that he never forgave the President.

*

Again, to be fair, the President may have had more urgent matters on his mind. The same week my stepfather posted his very good letter, an American U-2 spy plane photographed nine medium-range ballistic missile bases under construction near San Cristóbal, on the island of Cuba.

But rather than assuage my stepfather’s feelings, the Cuban Missile Crisis only added more fuel to his already blazing indignation, since it was Khrushchev, of all people—that fat-faced, bald, shoe-banger, the same Khrushchev who had given the heretofore guiltless homburg a bad name—who’d pulled a fast one on our hatless, hapless President. Proving, if proof were indeed necessary, that Hatless Jack wasn’t merely uncouth: he was dangerous.

*

But Communist dictators and Presidents come and go, as do fashions and fads, while what is enduring endures. And (Walter J. Waple, Jr. proclaimed) men’s hats would endure; they would stage a come back. “Upon my word they will,” my stepfather insisted.

*

Meanwhile my mother did everything in her power to get my stepfather to give up his hat store and take up some more profitable line of work. When she learned that Boris Stefansky—the same Boris Stefansky who fished me out of the waters of Candlewood Lake—had been promoted to manager of the wire clothes hanger factory where he worked in Waterbury, and that he and his company were looking to hire a new director of marketing and sales, she urged her new husband to interview for the position. “Why you’d be so good at it, Walter,” she said.

“Upon my word, Gladys, I’m a hat merchant, not a wire hanger salesman. What in the world do I know about selling wire clothes hangers?”

“But you’re such a good salesman! A good salesman can sell anything! Isn’t that what they say?”

(All this I happened to hear as I came down the stairs in pursuit of a glass of Cocoa Marsh and milk. I stopped and stood outside the parlor, listening at the beaded curtain.)

“They may say it, but it’s a bunch of hooey, if you will. A salesman can’t be expected to sell what he has no passion for, and I have no passion for wire clothes hangers. I don’t even like the darned things, always getting tangled up in each other.”

(A match was struck, its sulfur stench reaching my nostrils. In the parlor next to his chair my stepfather kept a rack with seven pipes in it — cherry, briar, meerschaum, corn-cob ¼ one for each day of the week. The man was a fuming human calendar.)

“You could at least consider it, Walter,” my mom said as another match was struck, this one for her cigarette. Though from where I crouched I couldn’t see her, I imagined her stretched out on the sofa in her bathrobe with her dancer’s legs, a cigarette in one hand, her sherry glass in another, that week’s crossword puzzle splayed open in her lap.

“A hat is one thing,” my stepfather said, “a wire clothes hanger is another, as it were.”

“At least people need clothes hangers.”

“If you mean to imply that men don’t need hats, I beg to differ.”

“President Kennedy doesn’t need one.”

“President Kennedy, if you’ll pardon my French, is a bloody moron, so to speak.”

*

A few months later, when my mother learned of a job opening in the men’s accessories department at Sears & Roebuck, she confronted him again. This time they were seated in the breakfast nook. Sunshine dazzled the frilly yellow kitchen curtains. From my mother’s Chesterfield tendrils of bluish-gray smoke arose, circling the half-moon glasses that made her look twice her thirty-three years.

“Upon my word, Gladys, I’ll have no part in such an undertaking, so to speak.”

“Why not? You’ll still be selling hats!”

“A hat is not an accessory. A scarf is an accessory. A glove is an accessory. A hat is a garment!”

They argued. There were bills to pay. How did he propose to pay the bills?

“I’ll take out a mortgage on the house.”

“You’ve already done that!”

“I’ll take a second mortgage.”

“What makes you think they’ll give you one?”

“Joe Kermode at Union Trust has always had faith in me. At any rate, my dear, I have no intention of giving up the store, so I beg of you, please, if you will, put an end to this harangue.”

*

In fact my stepfather did take a second mortgage on the house. Half of it went toward paying off bills; the other half toward remodeling his store. He installed marble vestibule tiles, wall-to-wall carpeting, and new display cases designed and built by Virgil Zeno, with mirrors and lights built into them. He replaced all of the store’s incandescent bulbs with fluorescent ones. He ran catchy new ads: Waple Hats—Where Hats Make the Man! Genuine Hats for Genuine Gentlemen! Beautify America—Wear a Hat! Still sales remained flat.

Yet my stepfather would not give up. He couldn’t give up. For my stepfather, selling hats was more than a business, it was a way of life, a philosophy, a matter of principle. And hats were more than something men wore on their heads; they were a symbol of masculine progress and pride, a synonym for civilization. A man without a hat was no better than one without shoes or a shirt. Even the lowest factory employee wore his hat in public if he had any couth. It might be a rough hat of inexpensive wool felt, or a tweed or a leather cap, and badly stained and battered. But he’d wear it with no less pride than a king wears his crown.

Society had merely entered a hatless period; like any seasonal virus, it would eventually run its course. The white corpuscles of reason would soon come to the rescue, bringing men back to their senses—and to their fedoras, their pork pies, their homburgs, their derbies, their panamas, their trilbys.

The dark days of hatlessness would pass.

[1] In fact Vice President Johnson did hold out his hat to cut the glare, but too late.