Editor’s Note: For the first several months of 2022, we’ll be celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts.

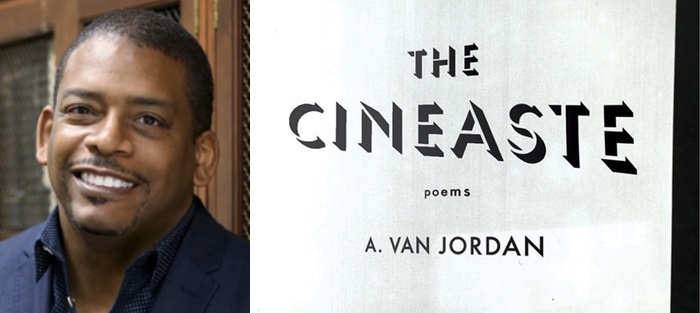

In today’s feature, Leah Falk talks with poet A. Van Jordan about his film-focused collection The Cineaste, persona, and form. This interview was originally published on April 29, 2013.

A. Van Jordan’s tastes and habits are “those of a writer,” as Saul Bellow once put it, meaning he is a voracious generalist. His second book, M-A-C-N-O-L-I-A (W.W. Norton, 2004) imagines the life of MacNolia Cox, who became the first black student to reach the final round of the National Spelling Bee; Quantum Lyrics (W.W. Norton, 2007) merges superhero comics, autobiography, and the philosophical principles of quantum physics. Besides being able to take compelling narratives and pack them into the artful arrangements of his collections, Jordan looks for new poetic forms in places others might not see them: in dictionary entries and, most recently, in the standard formatting of a screenplay.

His new collection, The Cineaste (W.W. Norton, 2013), merges the form and content of an obsession, film, to produce poems tracking the inner lives of movie viewers, the career of early black filmmaker Oscar Micheaux, the story of the Leo Frank trial, and the disturbing racial history of the American film industry. Forms both received and appropriated tell interweaving, nearly epic stories of our emotional identification with the movies we watch and the potential of film to define or destroy a people’s history.

A. Van Jordan was born and raised in Akron, Ohio. He began his academic training at Wittenberg University, Springfield, Ohio, for his BA in English Literature. He also holds an MA in Communications from Howard University and an MFA in Creative Writing from the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College. His first book of poetry, Rise (Tia Chucha Press, 2001), won a PEN/Oakland Josephine Miles Award and was selected for the Book of the Month Club of the Academy of American Poets. The book tracks not only the history of African American music, but also the music of Jordan’s life growing up in Ohio. Jordan is the recipient of numerous literary accolades, including a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Whiting Writers Award.

In his office at the University of Michigan, where he serves as a Professor of English and Creative Writing, I spoke with Jordan about his intentions for this new work, and what’s changed about the way we go to the movies.

Interview:

Leah Falk: One of the things that I like about this book is that you’re using sonnet sequences, film, persona poems, and elements of epic. Did you start out planning to incorporate all those things, or did some just seem appropriate as you progressed?

Van Jordan: I think the initial idea of the book came from a lunch I had with my former editor [Carol Houck Smith], who is now deceased. We had lunch one day after Quantum Lyrics had been out for a while and she was talking to me about the idea of an entire book structured with the screenplay formatting. She asked me what I was working on, I was telling her about the Oscar Micheaux project, and she thought that seemed like the perfect project for this. And so I started the process of researching and trying to write poems, initially thinking about Micheaux as the full focus of the book.

Van Jordan: I think the initial idea of the book came from a lunch I had with my former editor [Carol Houck Smith], who is now deceased. We had lunch one day after Quantum Lyrics had been out for a while and she was talking to me about the idea of an entire book structured with the screenplay formatting. She asked me what I was working on, I was telling her about the Oscar Micheaux project, and she thought that seemed like the perfect project for this. And so I started the process of researching and trying to write poems, initially thinking about Micheaux as the full focus of the book.

But the thing that was difficult to do was think about the influence [Micheaux’s work] had on filmmakers after him. What I wanted to do was contextualize where Micheaux was as an artist; John Sayles and Spike Lee might be the two independent filmmakers who have come close to the record that Micheaux had. He had over forty films; some of them at this point are considered “ghost films” because there’s no trace of them except maybe some review in a newspaper; but he did that work, and he did it without studio backing.

So that was the initial idea. I was thinking about the ways in which, one, we become artists, and, two, the ways in which an art form develops. So he’s at that point where film is just becoming—he develops it, he starts to develop the “race” film of that time. He’s in direct conversation with D.W. Griffith’s [Birth of a Nation, 1915] and all these other racist films that come out of the same period. We think of Griffith’s film as being the most racist film, but there was an inferior film that was almost as successful, and it was called Nigger. It released that same year. So there’s this wave of obvious resentment with this art form because blacks were seeing it being used as propaganda.

The Klan had died out after Reconstruction, but with Birth of a Nation and others, Klan chapters started sprouting up again. And Klan activities were pretty heavy by 1919, when Micheaux’s first film [The Homesteader] came out. That was sort of [his] inspiration.

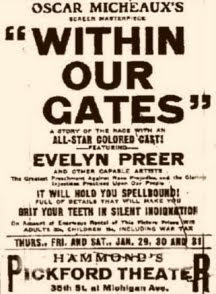

Micheaux’s film Within Our Gates [1920] was supposed to be a response to Birth of a Nation.

Within Our Gates and some of The Symbol of the Unconquered [1920] are supposed to be in direct response. Micheaux himself says no, but it’s clearly in response to that film. Also, his hero was Booker T. Washington, who was working with a group of filmmakers to try to do a response to [Birth of a Nation] but died that year. So it seems to make sense that that would be part of his mission.

From what I read it sounds like there was initial resistance to Within Our Gates because people thought it would spark an opposing wave of protest?

Yeah, the censor boards weren’t open to it. This was a big part of his career, having his films chopped up. The film he’s most known for, probably his best-preserved film, is Body and Soul, from 1925. That was a nine-reel film, bigger than The Homesteader and Within Our Gates, but it was cut down to five reels. This was the first film that Paul Robeson appears in. He’s already a big star with Emperor Jones on stage in 1920, and he’s only twenty-seven, so it was a real coup to get him in that “race” film. But it’s not the director’s cut. It’s still beautiful, though.

The central sonnet sequence in The Cineaste, about the making of The Homesteader and Micheaux’s life, reminded me of Ellen Bryant Voigt’s Kyrie, which wonderfully treats an historic moment in sonnets; and Michael Ondaatje’s Coming through Slaughter. Angels in America also popped into my mind. I think the reason I make those associations is that I think of them as American epics. They’re suggesting things we associate with epic, they’re really big and muscular, but at the same time they’re all treating marginalized material, material that has been nearly forgotten. Were you thinking of epic in that sense?

Sort of. I mean, it sounds like hubris when someone says, “I’m going to write an epic,” like they’re Dante or something. But in the sense that I wanted a central figure that we would track by chronicling the history and culture of a people—in that sense, yes; I wanted this to be a sustained look at a figure, to tell that story. So in a way we could say the initial effort was having something on the epic scale. It’s forty pages, so I’m not sure if that’s on the scale. But just the luxury of that sustained look was the thing I was after.

Also, in a more practical way, teaching while trying to write sometimes makes it difficult to have a completely new intellectual engagement every time I approach the page. So having this one idea or person I’m focusing on was more economical for my time while I was trying to do all these other things here in the department.

I wanted to talk to you about persona, because so many of these poems are either explicitly persona poems, like when you’re speaking in the voice of Oscar or Mary Phagan, but in the first and third sections you’ve also got someone watching a film, or talking about the experience of seeing a film, and to me those poems gradually become persona poems. It’s almost an experience of watching or watching secondhand that makes the viewer identify with the character. That seems to me really challenging—where is the border between being a member of an audience and becoming a persona, actually taking on the character?

I think on one hand I’m thinking that the viewer does become a persona; whether that persona is singular or plural is the thing that I’m not always as clear on. But I certainly think that there is a singular experience; we’re in the process of viewing the viewer, if that makes sense. So we’re seeing what that experience is like for the voyeur or the viewer.

In that first poem, “Metropolis Restored Edition,” I was at the Michigan Theater, and when I got there I didn’t expect to see what I saw, which was a line going all the way down the block. There was nowhere to walk, nowhere to park; people had come in from all over the state because there were only a few places in the country where they were showing the restored edition. What the theater did was hold the [showing of the] film for over thirty minutes. They said, “Once we start, we don’t want people coming in; we want to have the experience of watching this together.” They came out and explained this to us, those who were already seated, and people clapped. It was incredible.

Then, once the film actually started, everyone was rapt with attention—and it’s a three-hour film. I noticed very few people getting up to go to the bathroom and coming back, and when they did, they scurried out and scurried back. It was a very different experience. When I go to a multiplex, when I’m watching Judd Apatow or Tyler Perry, this kind of thing that people go to for complete relief, folks aren’t paying attention in the same way. They’re texting, getting up. I think that we’ve lost something in the experience of being moviegoers. Having the organist there [at the Michigan Theater], and a composed score for the showing, makes it a singular experience. There’s something about that that I was hoping to render in the collection.

The other part—this is closer to your question—is not so much rendering a person or persona as rendering an emotional experience. The experience of being a viewer in that audience was very different than being a viewer in any other audience. The experience of watching The Great Train Robbery is different than watching a film about a heist in a train today. So trying to capture that experience was the thing I was thinking about most when I thought about persona. A function of thinking “what is the emotional iconography of that experience that I’m trying to render here?”

There’s a moment in that central sequence where you’re writing in the voices of anonymous African Americans going to the movies. The line “At the movies, we keep our minds on each other” seems to have two meanings: we’re going there to be together, and also that humans go to the movies to focus on humanity. But film seems to have another, incendiary power during this time: Micheaux makes a movie to combat the portrayal of African Americans as inhuman, and Birth of a Nation sparks the re-incitement of the Klan. Do you think that film still has that power, and are you suggesting that with some of these poems?

Here’s the thing that’s fascinating to me. Film has probably the most influence on society as an art form because it reaches out to larger segments of society, and it has the distributive power to do that. But I think poetry has the greatest freedom of all art forms. When I think about commerce and the collective effort that goes into making a movie or putting up a play, having a gallery showing, a dance production, orchestral performance—everything takes this larger collective effort, and often it’s incredibly temporal, so you know this is a singular performance, this night, this audience. With poetry, we have the power to do pretty much anything we want. The people who are helping us distribute this work, they understand there’s not a lot of money in it, so there’s not a lot of meddling.

So it’s a very different kind of enterprise. On some level, yes, film has a great influence still. But I think when people are exposed to and/or confronted with a poem, I think it’s striking to them. I’ve done readings in prisons—when you see the faces of people who are really getting it, in that way for the first time, you know that it does have that power. There just aren’t as many venues for it.

I’m curious about what you think about form—the dovetailing of film and poetic form in this book. There were a lot of interesting points where there’s tension or irony between form and content. Micheaux wants to make a two-dimensional object to show the three-dimensionality of African Americans. One poem plays with elements of both the sonnet and blues. What do you think about the marriage of forms in the book?

I don’t think there’s any art without form. I could be wrong, but I don’t feel like it’s as big of a polemic in other art forms. You hear people talking about breaking from form, or pushing against form. But I don’t talk to many artists who’ve said they haven’t studied form, or they don’t respect it in some form. With poetry I find there are labels: someone writes a sonnet and suddenly they’re a neo-formalist. We use form like any other artist would, and I don’t think we can get away from it.

For me, when I’m thinking about how to render, how to manage information, how to structure something, the first place I’m gonna go to is form. Screenplay is probably one of the only writing arts that’s rarely published. We don’t study it in the same way, but it’s actually a very beautiful form. The issues we usually deal with inside of a poem or a story—they’ve worked all that out in their structure. When we think about transitions of time, transitions of place, the focus being on one character speaking to another, one voice shift, the voice inside someone’s head as opposed to the voice that’s more diegetic; all that’s worked out in the screenplay, and it’s all done through the formatting, so why not borrow that? The sonnet is a very flexible form, and of all the forms I can think of it’s probably the one that’s extended into the 21st century best. At the same time, there’s a certain limitation to it. You don’t want to spend the first sestet contextualizing, telling who’s speaking. So to get around that, I thought if we used the screenplay format, we could just go there. This time, this place, this person speaking.