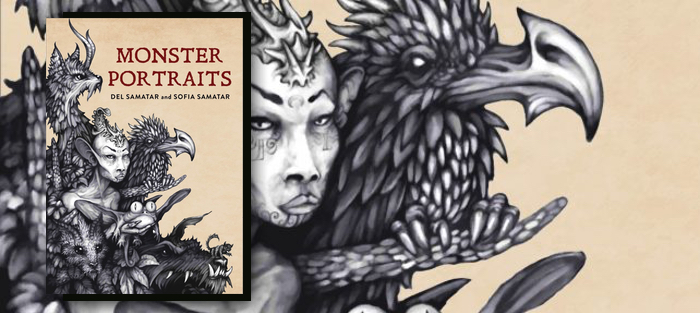

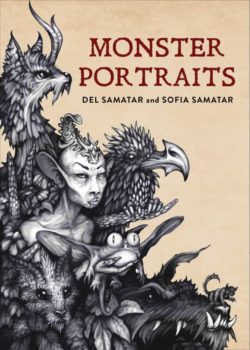

I read Del and Sofia Samatar’s Monster Portraits (Rose Metal Press) in one evening. Granted, it’s short—seventy-three pages total—but I’ve failed to finish slimmer books. I also don’t usually binge books, but I couldn’t stop reading. I love otherworldly stories, and the Samatars’ collection evokes that eerie, twilight ache I can’t resist. A catalogue of monsters with accompanying illustrations, Monster Portraits has the incantatory power of a story heard in childhood.

Like characters in a fairy tale, Sofia and Del Samatar are a brother-sister team. Del Samatar is a tattoo artist (it shows through in his fluid, minutely detailed illustrations). Sofia Samatar’s writing has been nominated for both Nebula and Hugo awards. In 2014, her novel A Stranger in Olondria won the British Fantasy Award.

Like characters in a fairy tale, Sofia and Del Samatar are a brother-sister team. Del Samatar is a tattoo artist (it shows through in his fluid, minutely detailed illustrations). Sofia Samatar’s writing has been nominated for both Nebula and Hugo awards. In 2014, her novel A Stranger in Olondria won the British Fantasy Award.

Part supernatural taxonomy, part travel diary, part fictional memoir, Monster Portraits is hard to categorize. In the opening story, “The Field,” the unnamed narrator calls her brother with an unusual proposal: “We should tell our lives through monsters.” He agrees via a text message reading only “Sounds dope,” and they set off.

On their journey, they meet a mermaid who seduces travelers with her descriptions of a beautiful kingdom so deep under the ocean that any human visitor would be crushed; three sisters in a castle who perpetually chase locust-eating saints off of their property; a Harpy imprisoned by her father; and a beautiful creature with a set of claws inside its chest which exist only for scratching at its own heart.

“How to move forward while preserving lightness?” the narrator wonders, at the outset of her journey. “How deformed can something get and still be a story?”

It’s a good question to ask, especially given that Monster Portraits is a collection of flash fiction. Flash is slippery, hard to define. It has poetry’s short form and attention to detail, its disregard for what is technically possible, and fiction’s love of character and narrative. Flash is a hybrid genre, not quite a prose poem but not a full story, either. Which makes it the perfect form for writing about the supernatural. Like flash, monsters are a blending of categories—a girl with fangs, a man with fins, a child with arms where its eyes should be.

So of course Sofia Samatar’s flash is a patchwork of story, history, philosophy, and what might be memory: “The Search” is made up almost entirely of search results for the word “monster” in Google Scholar. “The Knight of the Beak,” the story of a knight who falls in love with a fairy queen, is interrupted by the memory of the narrator and her brother watching Knight Rider in their childhood living room. “The Collector of Treasures” is part catalogue of oddities and part meditation on Ambroise Pare. A French barber surgeon commonly understood to be the father of modern surgery, Pare also authored the book Des Monsters et Prodiges (On Monsters and Marvels). Of Pare, Samatar writes:

I think Ambroise Pare would have liked me…I think I would have impressed him…I think [he] would have served me one of his tisanes while I behaved in a most creditable manner. I think he would have asked me to have a seat at his little table. I think he would have done something awful to me with tongs.

That last line…I both expected it and felt, when it finally came, like I’d tripped walking down the stairs. Sofia Samatar captures that horror movie combination of expectation and dread in her work. She never lets you rest. The line also evokes Saartje Baartman and Tuskegee, people lured in by the promise of a better life, then destroyed in the name of science. Another way of saying this is: these are fantasy stories, but they also aren’t. The narrator and her brother are telling their lives through monsters, and what’s more monstrous than history?

Sofia and Del Samatar are of Somali/Swiss-German descent, and much of the text—and subtext—of Monster Portraits revolves around race and what it means to be multi-racial in a world that insists on categorization. If you are not purely one thing or another, does that make you monstrous? What does it mean to dissect the ways in which you are like no one else? What does that do to you?

Sofia and Del Samatar are of Somali/Swiss-German descent, and much of the text—and subtext—of Monster Portraits revolves around race and what it means to be multi-racial in a world that insists on categorization. If you are not purely one thing or another, does that make you monstrous? What does it mean to dissect the ways in which you are like no one else? What does that do to you?

“The world is a hall of images,” Samatar writes. “None of them ours.”

But Monster Portraits also makes it clear that there is power and loveliness in unlikely designs. This is due in large part to Del Samatar’s illustrations, which have a spooky elegance. They are indisputably drawings of monsters, but they are beautiful monsters.

Sofia Samatar’s prose carries this message as well. Near the end of their journey, the unnamed brother and sister come together in a cabin in Colorado to compile their notes and illustrations. Looking over their work, the sister reflects:

“Try to copy something exactly. Impossible. You can transfer every word and still, in the margin, this unfolding fin, this nub of horn, this tail…Try as much as possible to conform and you will be saved by a wily grace. Imperfection is your genius.”

Boundaries blur inevitably. The search for purity leads to nothing but suffering. If Monster Portraits has a moral (and, since it’s a fairy tale, it should), I think that’s it.