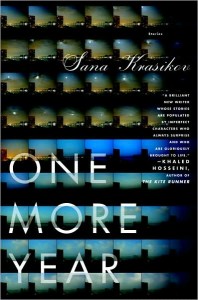

The title of Sana Krasikov’s debut collection, One More Year, suggests both despondency and hope, both reluctance and anticipation—wonderfully fitting for a book about immigrants from the former Soviet Union. As these characters navigate terrains of exile, loneliness, and desire, they confront the obvious impossibility of being two places at once while maintaining a deep desire to elude this. The problem of their exile, then, lies not in thinking simultaneously of two places but instead in dreaming of forever remaining in both. The idea of choice becomes paramount. In the first story, “Companion,” Krasikov describes one character as follows: “She had been thirty-two then, not young, perhaps, but young enough for her choices to seem reversible.”

The title of Sana Krasikov’s debut collection, One More Year, suggests both despondency and hope, both reluctance and anticipation—wonderfully fitting for a book about immigrants from the former Soviet Union. As these characters navigate terrains of exile, loneliness, and desire, they confront the obvious impossibility of being two places at once while maintaining a deep desire to elude this. The problem of their exile, then, lies not in thinking simultaneously of two places but instead in dreaming of forever remaining in both. The idea of choice becomes paramount. In the first story, “Companion,” Krasikov describes one character as follows: “She had been thirty-two then, not young, perhaps, but young enough for her choices to seem reversible.”

Perhaps uncertainty is fueled by the maddening sense that one choice will undeniably negate countless other options, and it’s this anxiety of indecision, or, perhaps, of decision, that runs through all these stories, afflicting its characters. And because so many of these characters have chosen things that have irrevocably changed their lives, subsequent decisions become all the more difficult. So the characters hesitate. In their surroundings, in their relationships, they fade to sketches of themselves, carbon copies that look the same and sound the same but are somehow not filled out.

All of Krasikov’s characters are waiting for their real lives to begin. In “Companion,” Ilona lives with an elderly man named Earl; she only stays with him because she cannot yet afford an apartment of her own. Their relationship is not sexual—Earl is impotent—but it bears many of the trappings of a marriage.

At her friend Taia’s house, Ilona slides her rings back on after slicing some watermelon. Taia warns her to be careful to not lose them. “One day you’ll take one off and it will fall down a drain. Some women don’t even wear the jewelry they own. They have copies made.”

Taia seems more comfortable with copies of things. Although she is well off and fortunate to have so much, she seems hesitant, as if she’s not quite entitled to her life. Ilona describes her friend’s kitchen as having the best appliances and granite countertops, things Taia only uses when entertaining.

Ilona, responding to Taia’s comment about the rings, wryly suggests perhaps she should tie a piece of tinfoil around her finger instead, a gesture that perhaps signifies two things: (1) the tying of a string as a reminder of something, and (2) a lesser copy of a wedding ring for what Illona essentially has—a lesser copy of a marriage.

In Tbilisi, Ilona had had both a husband and a lover, and now she has watered down versions of both. Her current lover, Tomas, has a wife and family still in Georgia, is therefore doubly absent. He is not only unavailable in the way a married lover is, but also because his marriage exists across the Atlantic he is doubly removed.

The one time we see Ilona and Tomas together in present action is, appropriately so, not in either of their homes—both have less-than-ideal living situations, and neither have places they’d call their own. Instead, Tomas visits Ilona at Taia’s while Taia and her husband are away:

[Ilona] imagined she’d take great pleasure in showing off Taia’s house…. And yet it was not her character, and she had to repress the urge to say that she might have done the room differently, that she would have placed the furniture closer to the windows or painted the walls a brighter color, a color she could wrap herself in.

Ilona is painfully aware of what is not hers and therefore about which she might not be entitled to an opinion. It is worth mentioning that her earlier affair was with none other than Taia’s husband, Felix, further complicating her feelings of proprietary rights.

This idea of settling for only so much is threaded throughout One More Year. In “Better Half,” twenty-two-year-old Anya marries a customer from the restaurant where she works, but soon, because of his violent behavior, files a restraining order to which she is hesitant to commit. And she recognizes this act is not enough to turn off her longing: “It was over with Ryan, she knew, though it would take time for her desire for him to pass.” But the most heartbreaking line in the story is when Anya wonders if once, early in their relationship, she really did love him. “After all,” she muses, “who else was there to?” She can’t imagine anything better for herself.

The title character in “Maia in Yonkers,” in contrast, dreams of a better life for herself and her son, who remains in Georgia, but she is unsure when exactly it will start: “It is almost seven a.m., four in the afternoon in Tbilisi,” the story begins, immediately displaying the acute, ever-present awareness of time zones only held by those with an attachment to something in another. Maia, who works as a live-in home-care aide, is supporting her son from abroad, a relationship that is strained with expectation, manipulation, and guilt.

In another story, “The Alternate,” communities of émigrés are beautifully described as “An entire world transposed, like an ink blot on a folded map, from one continent to another.” And with the transposition, maybe this transferred ink blot fades a little while the original shines all the brighter.

These characters’ states of exile make them feel unentitled to their present location and more fiercely entitled to where they are not. And perhaps this imbalance completely estranges them from both, unable to stake a claim for either reasons of misdirected allegiances or the guilt of a heart in the wrong place. Perhaps the lack of entitlement to the world in which they live stems from the guilt inherent in leaving another behind.

In many ways, the only thing these characters can fiercely claim is their pasts, where their lives are still fully formed. In “There Will Be No Fourth Rome,” the narrator is staying in Moscow with Larissa, a friend of her parents. Another friend has just referred to Larissa’s partner as Larissa’s husband, which surprises the narrator. She muses: “The only person to whom Larissa still referred as her husband was Alexei, who died nearly twelve years ago.” Misha only “stayed” in Larissa’s apartment during the week––the verb stayed here is an interesting choice, as it implies more of a visiting than an actual residence––because he “took the train to Saltykovka where he was building a dacha for his son and daughter. He had divorced their mother ten years before…and even now felt guilty.”

Finally, in the aforementioned “Companion,” Ilona’s lover, Tomas, had been a doctor in Georgia and now, in the States, worked as a carpet-layer by day and supermarket cleaner by night. He talks of being a twenty-five-year-old doctor in Abkhazia and encountering even younger soldiers: “Nobody taught them anything. They didn’t even know how to part with the dead.”

It’s an unsettling statement, the idea of being taught to part with the dead. Many of this book’s characters are still struggling with such, and Krasikov paints them with stunning sensitivity, whether they are parting with a the memory of a lover, a dead spouse, an abandoned country, a way of life that’s vanished. Even if they go back, they might find a place they simply don’t recognize, as if nothing has died but instead has been slowly disappeared: a painting, a sketch, bits of eraser dust scattered across the page.

Further Resources

– Read a story from One More Year: “Maia in Yonkers” was first published in the Atlantic‘s 2008 Fiction Issue.

– Bostonites: See Sana Krasikov read (with Tom Perrotta) at 8 PM on December 1 as part of the Blacksmith House Reading Series, 56 Brattle Street, Cambridge, MA 02138

– Krasikov discusses her fiction with Leonard Lopate.

– The author talks about “the first Soviet-Jewish Generation”: