The Past, Tessa Hadley’s sixth novel, concerns a family engaged in the messy business of beginning to break up a house. Four adult siblings and assorted others (one brand-new spouse, three children, and a guest) gather at the family’s late grandparents’ home for a three-week holiday—probably the last family reunion before the house must be sold. The three older siblings lived in the house with their mother, Jill, in 1968, during a separation in their parents’ volatile marriage. Later, their grandparents and the home served as anchor and refuge for all four children following Jill’s early death. Now the adult siblings—confined in emotionally and physically close quarters on this holiday; surrounded by familiar objects, books, and troves of old letters— find the anticipation of the likely sale of the house stirs memories of prior losses and provokes present conflicts.

As in classic British country house mysteries or psychological thrillers, the cast of characters is cut off from their usual outside worlds and distractions. Even mobile phone reception is spotty. Of course, Hadley writes neither conventional mystery nor thriller (the only dead body discovered is a dog’s—the two youngest children stumble upon it, and a stash of pornography, in a crumbling cottage on the property). Rather, the mystery and the thrills here are the universal ones: how relationships both change and endure over time, the impact of sex and yearning, love and betrayal, and secrets. With her customary depth, compassion, and wit, Hadley explores the vexations of togetherness and separateness, the puzzle of core individual and family identity.

Setting up the story with dramatic flair, Hadley assembles her cast with a bustle of sequential arrivals; inhabiting the point of view of every character while unifying the shifting viewpoints with a subtle omniscience. First the reader meets next-to-youngest Alice, forty-six but self-absorbed as an adolescent. She has brought her former boyfriend’s twenty-year-old son, Kassim, along, without asking her siblings. Next to arrive is the youngest—worker-bee Fran, without her feckless musician husband but with the groceries and her children: nine-year old Ivy and six year-old Arthur. Quiet eldest sibling Harriet slips in after hiking solo in the countryside in preparation for the intensity of family togetherness. Brother Roland, an academic whose sisters “half-worshipped his cleverness” but “also found it slightly ridiculous,” joins the party last, pulling up in his Jaguar, accompanied by teenage daughter Molly and his third wife: glamorous Argentian attorney Pilar.

Setting up the story with dramatic flair, Hadley assembles her cast with a bustle of sequential arrivals; inhabiting the point of view of every character while unifying the shifting viewpoints with a subtle omniscience. First the reader meets next-to-youngest Alice, forty-six but self-absorbed as an adolescent. She has brought her former boyfriend’s twenty-year-old son, Kassim, along, without asking her siblings. Next to arrive is the youngest—worker-bee Fran, without her feckless musician husband but with the groceries and her children: nine-year old Ivy and six year-old Arthur. Quiet eldest sibling Harriet slips in after hiking solo in the countryside in preparation for the intensity of family togetherness. Brother Roland, an academic whose sisters “half-worshipped his cleverness” but “also found it slightly ridiculous,” joins the party last, pulling up in his Jaguar, accompanied by teenage daughter Molly and his third wife: glamorous Argentian attorney Pilar.

The story’s setting—the house, the nearby cottage, the surrounding woods and farmland—is more even than the essential context and frame for the family and the novel. Speaking of The Past (then a work in progress) at the International Small Wonder Short Story Festival, the author said, “the house is the center of the whole book” and explained she is intrigued by rooms as metaphors: “charged, expressive space.” Here the particular bedroom each person chooses (or is assigned) furthers the story. Alice claims her favorite room; reluctant Fran must bunk with her children to provide both niece Molly and uninvited outsider Kassim individual private rooms. Reticent Harriet sleeps in a small room only accessible through its two adjoining neighbors: Alice’s room or Roland and Pilar’s. The first night she notices “… the door in the other wall, which led into her brother’s room, had been left open—although she had been careful to close it earlier.” She can’t resist eavesdropping:

The light wasn’t on in there either, but she could hear Roland and Pilar moving around … Embarrassed … Harriet slipped out of her shoes and went stealthily across the room to close it. The full moon had risen and was shining in at all the windows on the back of the house; blue light spilled through the open door into her room. Her brother and his wife must be bathed in moonlight.

In this incident and many to follow, the house itself and the interlocking physical spaces of the rooms contributes to rising tension between the inter-connected family members.

And so from the outset—characters gathered, places assigned—the author engages the reader with a complex, rewarding story of a loving and competitive family, grappling with questions of inheritance: concrete and intangible, genetic and experiential. Fittingly, this is also a work which demonstrates the impact of literary inheritance, the importance of an author’s literary family roots, her literary ancestors’ influence on her subject and style. Hadley is a clear descendant of many fine British novelists; in particular, her wise, wry consideration of relationships, especially marriages, brings George Eliot to mind. Another literary ancestor apparent here is Elizabeth Bowen. In the author’s Acknowledgements section, Hadley says that the three-part structure of this novel—The Present, The Past, The Present—is borrowed from Elizabeth Bowen’s The House in Paris. Hadley’s comment sent me back to re-read this novel of Bowen’s. Echoes between the two books resonate beyond structure to include theme, tone, and sensibility. Both pivot around a mother (Hadley’s Jill, Bowen’s Karen) who is a pervasive absent presence in the narrative present sections but the essential point of view character in the middle section—The Past. Additionally, in both works there is a brilliant sensual rendering of domestic and landscape settings that is inviting and realistic as well as powerfully symbolic. And both authors enter the point of view of children with authenticity and without sentimentality—in a manner also reminiscent of another of Hadley’s literary forbears: Henry James.

Hadley, in addition to her celebrated fiction, is the author of Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure (Cambridge, 2009). James provides the other dominant strand of literary DNA most in evidence here. Passion—real and imagined—pleasure, and pain, are very much part of Hadley’s fiction and this particular family’s experience. However, the primary Jamesian fingerprint in this book is Hadley’s canny inhabiting of a prescient child’s perplexed observations, partial understanding, and intuitions about the sex-driven behavior of the adults in her world. Nine-year-old Ivy—overwrought, curious, and meddlesome—snoops, spies, vandalizes a diary, and helps orchestrate trysts. She is a direct, worthy descendent of the sinister children in The Turn of the Screw and wise naïve Maisie in What Maisie Knew.

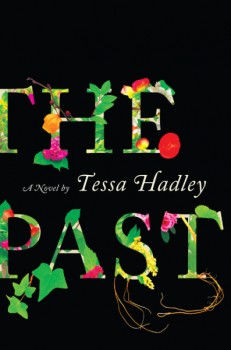

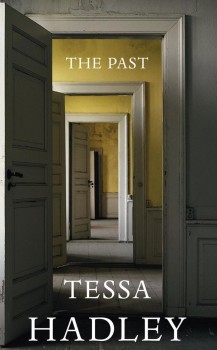

Although a quintessentially British author, Hadley is universally accessible and widely read here. I read both the British (Jonathan Cape) and the American (Harper) editions as my husband, knowing how eagerly I await and pounce upon each Hadley story in The New Yorker, ordered the British edition before even the review copy of the American edition was available here. A striking difference between the two, likely reflecting marketing assumptions about audience sensibility, is the contrast between the two very different covers. The Cape cover depicts a telescoping series of doorways opening into serene, light-filled, adjoining rooms—evoking a modern version of a Dutch genre painting, playing with perspective and vanishing point; referencing the role of domestic space in this novel. This British cover is a quiet, reflective, mysterious image inviting and enticing the reader to find a quiet corner, a comfortable chair, and read. By contrast the Harper design features the title spelled out in vivid botanical letters—twining fragments of trailing ivy, roots, leaves, and flowers. It suggests a pop-culture illuminated manuscript, or an alphabet cut from an almost hallucinogenic wallpaper co-created by biologist Gregor Mendel and pre-Raphaelite artist William Morris. This cover shouts for attention, like graffiti: a demanding imperative to buy and read.

Although a quintessentially British author, Hadley is universally accessible and widely read here. I read both the British (Jonathan Cape) and the American (Harper) editions as my husband, knowing how eagerly I await and pounce upon each Hadley story in The New Yorker, ordered the British edition before even the review copy of the American edition was available here. A striking difference between the two, likely reflecting marketing assumptions about audience sensibility, is the contrast between the two very different covers. The Cape cover depicts a telescoping series of doorways opening into serene, light-filled, adjoining rooms—evoking a modern version of a Dutch genre painting, playing with perspective and vanishing point; referencing the role of domestic space in this novel. This British cover is a quiet, reflective, mysterious image inviting and enticing the reader to find a quiet corner, a comfortable chair, and read. By contrast the Harper design features the title spelled out in vivid botanical letters—twining fragments of trailing ivy, roots, leaves, and flowers. It suggests a pop-culture illuminated manuscript, or an alphabet cut from an almost hallucinogenic wallpaper co-created by biologist Gregor Mendel and pre-Raphaelite artist William Morris. This cover shouts for attention, like graffiti: a demanding imperative to buy and read.

Happily, the story’s text is identical. The novel will delight readers on either side of The Pond partial to exploring the wonderful and terrible experience of family life, particularly veterans of the physical and emotional upheaval attendant upon breaking up a family home. The Past is a marvelous read—whether your preferred cup is well-steeped tea (milk in first) or cold-brewed coffee.