In his foreword to The Georgia Review’s 300-page Spring 2011 retrospective, editor Stephen Corey addresses every possible audience that might have picked up his journal, from bona fide subscribers to online visitors to bookstore browsers to those lucky souls who might have stumbled upon its pages left behind on a “plane, subway, bus, park bench…”

In his foreword to The Georgia Review’s 300-page Spring 2011 retrospective, editor Stephen Corey addresses every possible audience that might have picked up his journal, from bona fide subscribers to online visitors to bookstore browsers to those lucky souls who might have stumbled upon its pages left behind on a “plane, subway, bus, park bench…”

Perhaps the only category of reader not listed is you, the future FWR-referred reader, introduced to The Georgia Review through this write-up—or perhaps through the random drawing for a free subscription that will occur next week.

But don’t be intimidated—you’ll be amongst friends right from the Table of Contents. At the end of the Spring issue’s foreword, Corey announces the journal’s nominations for the National Magazine Awards competition. In fiction, Corey and his colleagues chose to sponsor the Pushcart Prize-winning “The Lobster Mafia Story” by Anna Solomon, whom Fiction Writers Review interviewed just a few weeks ago and whose debut novel, The Little Bride, was named our Book of the Week.

“The Lobster Mafia,” was, in fact, my introduction to Solomon’s work. The story explores the relationship of a wife and husband in the aftermath of a violent crime the latter commits with a gang of fellow lobster catchers. The men take the crime to their deathbeds, which is where we meet the narrator, Marcella, tolerating suspicious glances from the gang’s widows after her husband’s funeral. From the first page onward, we quickly learn she won’t grieve him so much as reflect on their marriage, rooted in Boston’s North End right beside the pride, resentment, and repression that kept them there:

They knew that I was not from here, either, that I’d grown up in Boston’s North End, praying to be delivered from the crowded, garlic-stinking streets, from family, from spinsterhood, from tackiness; that when Bobby finally found me, I was grateful to him the way you are grateful when the hairdresser makes your hair into something it isn’t, though you feel a little nervous, every time the wind lifts, that the style won’t last.

Emma, a curious young neighborhood girl, becomes the catalyst that helps Marcella understand how and when her marriage turned. Finding the freedom to tell Emma her story gives Marcella the freedom she never had when holding it inside.

In her interview with Sara Schaff here at FWR, Solomon states, “I actually feel like a really masterful short story is harder than a good novel because it’s such a demanding form. It feels much more particular, and if things are not perfect, it’s much more obvious.”

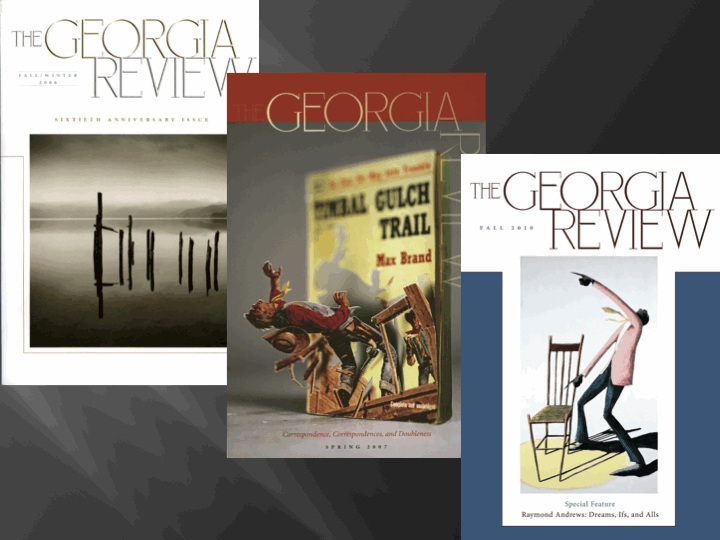

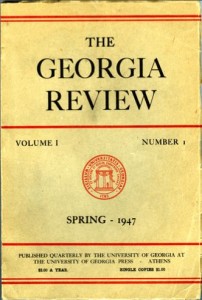

The Georgia Review has shared this commitment to storytelling since its founding in 1947. Heading toward its 258th issue, the journal has been recognized by the National Magazine Award in multiple categories: “Essays,” Single-Topic Issues,” “Fiction,” and—unsurprisingly, given this list’s breadth—“General Excellence.” But besides winning awards, the journal’s careful curating of stories, essays, poetry, reviews and art has helped it survive the test of time, which of course has included budget cuts and new production processes.

The Georgia Review has shared this commitment to storytelling since its founding in 1947. Heading toward its 258th issue, the journal has been recognized by the National Magazine Award in multiple categories: “Essays,” Single-Topic Issues,” “Fiction,” and—unsurprisingly, given this list’s breadth—“General Excellence.” But besides winning awards, the journal’s careful curating of stories, essays, poetry, reviews and art has helped it survive the test of time, which of course has included budget cuts and new production processes.

This curating has brought readers work from the likes of Joyce Carol Oates, George Singleton, Robert Olen Butler, William Faulkner, and Harry Crews. I discovered two pieces by the last in the most recent Winter 2011 issue: an essay in which Crews shares the real-life inspiration for the character Didymus in his novel The Gospel Singer, and an excerpt from the novel itself.

Though the first piece is nonfiction and second fiction, they read as a one-two punch of breathless narrative. In “We Are All of Us Passing Through,” Crews tells how he rode across the country fighting frostbite and a rational—yet hilarious—fear of rape at the YMCA, only to come face-to-face with something that represents the Devil and Jesus and what Crews is sure is his impending bloody murder.

Ten years after escaping the dreaded Y, this “wasted night” returned to the author when he set out to write The Gospel Singer, and the fourth chapter of the novel—excerpted later in the issue–shows how this real-life inspiration manifests itself through an imagination as vivid as Crews’. Having read Classic Crews: A Harry Crews Reader a few years ago, I relished the rare opportunity to cross-reference the moment of inspiration against the story it birthed. Not surprisingly, what emerged from that moment was wholly different, informed by the subconscious instead of the factual settings, characters, and descriptions that inspired it. Rather than simply narrate what had occurred in the YMCA, or create a character with a similar physical build or voice, Crews transferred the spirit of insidious evil from his night in the YMCA into Didymus. Crews’ nightmare gives form to Didymus’s motives and perspective, the justified heartlessness with which he operates.

Ten years after escaping the dreaded Y, this “wasted night” returned to the author when he set out to write The Gospel Singer, and the fourth chapter of the novel—excerpted later in the issue–shows how this real-life inspiration manifests itself through an imagination as vivid as Crews’. Having read Classic Crews: A Harry Crews Reader a few years ago, I relished the rare opportunity to cross-reference the moment of inspiration against the story it birthed. Not surprisingly, what emerged from that moment was wholly different, informed by the subconscious instead of the factual settings, characters, and descriptions that inspired it. Rather than simply narrate what had occurred in the YMCA, or create a character with a similar physical build or voice, Crews transferred the spirit of insidious evil from his night in the YMCA into Didymus. Crews’ nightmare gives form to Didymus’s motives and perspective, the justified heartlessness with which he operates.

Now’s as good a time as any to let editor Stephen Corey address you with our Journal of the Week question set:

What is the role of The Georgia Review in today’s literary community, be it for readers or writers?

Picky though this may seem, I find myself uncomfortable with the notion of a “role,” which to me implies, variously, something fixed, something “played,” and something about which one might allow oneself to feel self-important. I’d rather try to say a little about what I think The Georgia Review “does” that might be noteworthy within the broad literary community.

- We are among a relatively small number of magazines that regularly gives substantive space to four genres: essays, short stories, poems, and reviews.

- We have a special if understated commitment to publishing on a regular basis the most outstanding environmentally-conscious writing we can find, having featured such committed authors and thinkers as Barry Lopez, Pattiann Rogers, and Reg Saner. If we have no Earth we can live on tolerably and humanely, we will have no “literary community.”

- We have managed to institute and to maintain a payment scale for our contributors that may not be decent but is at least more than a token: fifty dollars per published page for prose and four dollars per line for poetry.

- We give a fair shake to every submitted manuscript because we recognize there is no predicting the source of the best pieces of writing—and this equal treatment of submissions is what leads to our publishing a significant number of previously unpublished and scarcely published writers. (I never use the term “slushpile” except when denouncing it, and I forbid my staff from using it or thinking in its shadow.)

We are heavily and sympathetically hands-on editors, working closely with our contributors to make their manuscripts as strong as possible before they go to press. Our writers do the great bulk of the work, of course, but I believe that good editorial work can improve even the best writing by a few percentage points. A few writers are annoyed by our proactive approach, but the great majority of them are appreciative—and even come to enjoy the back-and-forth effort.

- We are committed to producing print issues whose design and production details we take just as seriously as we do the manuscript details. If the world reaches a point where it has no need for beautifully printed books and journals, that world will have no need for The Georgia Review.

How do you see The Georgia Review’s mission and tastes evolving in the next two years? Will the rise of digital publishing impact the composition of The Georgia Review?

The stated mission of The Georgia Review is to present the best thought, writing, and visual art to an audience of intellectually open and inquisitive readers, both nationally and internationally. The tastes of the journal are, like those of any similar publication, those of its editor(s). The only ways these may evolve in the short term will be as they are incrementally influenced by whatever submissions are brought to bear upon the editorial staff’s thinking and feeling. I am quite certain any such changes would of necessity be small, yet at the same time they will be vital because The Georgia Review can be nothing except the communal, somewhat serendipitous creature produced by writers and editors in concert.

Sometime in 2012 we intend to make available by paid subscription a digital version of The Georgia Review’s print edition. The latter will remain the heart and soul of our operation, but we believe we can now offer an onscreen edition that, for those readers who want it, can give a mirror experience of our printed pages. (We have been offering various behind-the-scenes extras on our website for some time, and we will continue to develop those in the coming years.)

If you could put three items in a time capsule (or USB drive) to be opened in 1,000 years that would provide a snapshot of The Georgia Review’s aesthetic today, what would they be?

Well, the capsule can’t be sealed just yet because one of the three items isn’t ready to go. I’d include a copy of our Winter 2001/Spring 2002 double issue, which gives a retrospective of some of our best essays from the first fifty years of the journal, and a copy of Spring 2011—a retrospective of stories from the past twenty-five years that picks up where our forty-year retrospective (Spring 1986) left off. The third item, nonexistent, is a follow-up to our forty-year poetry retrospective (Fall 1986)—an issue I hope to bring out in 2013.

What album is playing on the The Georgia Review stereo these days?

See What Tomorrow Brings by Peter, Paul and Mary. I could write an essay on why I’m giving this response to such an impossible question, but I won’t. I’ll leave it to readers to spend a couple of years with the journal to see whether they can figure out some reasons behind my choice.

Beyond its core publishing missions, The Georgia Review serves the public with ongoing literary programs. You might recall the 1995 Cultural Olympiad, carried out in conjunction with the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. The Georgia Review produced two special issues for the signature event, as well as organized the largest-ever gathering of Nobel Laureates in Literature.

They’re also grooming future Laureates with a newly established writers’ retreat in Canon, Georgia. The hotel-turned-home will boast literary readings and events in addition to its Writers in Residence programs.

This March, you’ll be able to catch up on The Georgia Review in one fell swoop with their new book from the University of Georgia Press, Stories Wanting Only To Be Heard: Selected Fiction from Six Decades of The Georgia Review.

This March, you’ll be able to catch up on The Georgia Review in one fell swoop with their new book from the University of Georgia Press, Stories Wanting Only To Be Heard: Selected Fiction from Six Decades of The Georgia Review.

Until then, head to The Georgia Review’s official site for subscription and submission information, back issues, excerpts, and much more. Completing the southern (online) hospitality are the journal’s blog, Twitter feed, and Facebook page.

~

As a special bonus to readers of Fiction Writers Review, we’ll be giving away three free subscriptions to The Georgia Review! If you’d like to be eligible for this week’s drawing (and all future ones), please visit our Twitter Page and “follow” us.

As a special bonus to readers of Fiction Writers Review, we’ll be giving away three free subscriptions to The Georgia Review! If you’d like to be eligible for this week’s drawing (and all future ones), please visit our Twitter Page and “follow” us.

For those of you already in the FWR Twitter family, you know our presence there exists in part to inform followers of what’s happening here on the site, as well as to update the community on literary trends, worthwhile links, etc. We couldn’t be happier to see this role expand in a way that allows us to put journals we love in the hands of readers who will love them too.