I went through a phase right after college where I listened to the Ryan Adams album Heartbreaker, a lot, until the CD scratched. I can beat an album until it’s dead, and press on until the bones stand up and dance again. Say what you will about nostalgia, music will fix time and place like nothing else.

I went through a phase right after college where I listened to the Ryan Adams album Heartbreaker, a lot, until the CD scratched. I can beat an album until it’s dead, and press on until the bones stand up and dance again. Say what you will about nostalgia, music will fix time and place like nothing else.

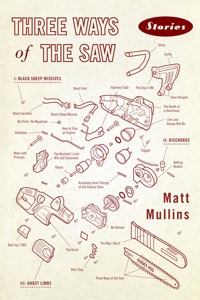

There’s music to the stories in Matt Mullins’s debut collection, Three Ways of the Saw. Nostalgia and longing that gets into the bloodstream and won’t let up until you see it through. The press materials from Atticus Books, a plucky indie press publishing some really fine new writers, liken Mullins to Cormac McCarthy, but that’s an imprecise shorthand. McCarthy’s work runs on epic rails. But within 230 pages, Mullins whipsaws through twenty-five intimate stories that leave you with snatches of lyrics and minor chords pounded hard and ringing in your ears.

Three sections compose the collection: I. Black Sheep Missives, II. Dischords, and III: Ghost Limbs. Black Sheep Missives follow one family, skipping back and forth in time and perspective. The stories concern the only son, in a sea of sisters, of a Catholic auto executive in Detroit, and how he parlays a childhood of advantage into a life disappointing to himself and parents alike. Flashes of crisis – the night  before his wedding or confronting his father’s mortality through a photograph – never pin down where things went wrong, only that they have. The reader knows what, but must speculate about how and why. The prose throbs with elegiac Americana, “The first time I heard my dad say fuck we were driving through Utah in a rented Winnebago.” This may not be your memory, or mine, but nonetheless has that inherited patina of stories that could be ours.

before his wedding or confronting his father’s mortality through a photograph – never pin down where things went wrong, only that they have. The reader knows what, but must speculate about how and why. The prose throbs with elegiac Americana, “The first time I heard my dad say fuck we were driving through Utah in a rented Winnebago.” This may not be your memory, or mine, but nonetheless has that inherited patina of stories that could be ours.

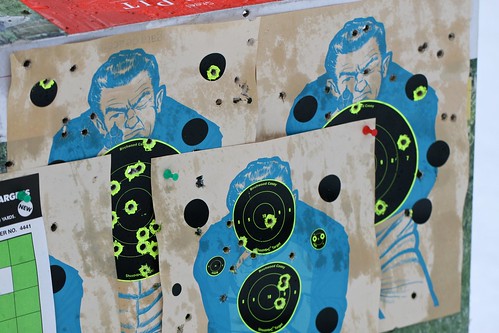

The characters in Dischords are one hot mess: prodigals on a grand scale who don’t bother with that returning home nonsense. They self-aggrandize, but one feels they’ve got a right to it, since they so clearly have very little else going for them. Mullins has honed these stories to fender chrome. Lines grab you by the windpipe – “What’s a woman except a shot to the heart that didn’t kill you but won’t heal.” Only very rarely did a sentence not quite land, proving just artful enough to pull the reader momentarily into the no-man’s-land between awareness of the construction and being submerged in a story. “I sip my nth cup of black.” But that same taut diction makes a story like “I Am and Always Will Be” – a single encounter between a self-centered guy and the obese woman downstairs – skip through the mind like a pinball long after its three-and-a-half pages end. When Mullins pulls it off, which is often, those shots go straight to the heart.

Ghost Limbs delivers on its promise – lost lung, lost arm, lost scalp. Reading these stories will set you on edge, awaiting dismemberment, for the torpedo to surface and clear the deck. If the first sections reveal characters who are their own worst enemies, the final stories remind us just how fragile the human machine really is. “The Braid” pulls off hair as main character, something I’ve not encountered save for O. Henry’s “The Gift of the Magi.” But where O. Henry plays at the edge of maudlin, “Braid” is a five-page jitterbug ending in a punch to the solar plexus: two wealthy, gorgeous, world-at-their-feet types at an idyllic picnic. Mullins seeds the bower of pleasure with a darker note, so that when the birdsong abruptly falls away, and horror shatters the idyll, you realize your stomach’s been in knots since the opening line.

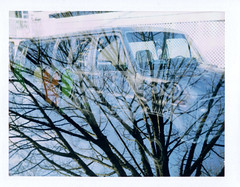

The title story, last in the book, is a masterpiece of perspective. An elderly man, dying from lung cancer, watches two younger men cut away a fallen honey locust he planted thirty years before. He hoped the tree would outlive him, but now he realizes his final days will be spent looking at the stump. His wife, a music teacher, clings to normalcy, “Because that’s what life does, it goes right on having accordion lessons in spite of us.” That “in spite of us” is the whole tragedy, these flesh and bones so brittle and frail in the face of all the accidents that could single us out.

The title story, last in the book, is a masterpiece of perspective. An elderly man, dying from lung cancer, watches two younger men cut away a fallen honey locust he planted thirty years before. He hoped the tree would outlive him, but now he realizes his final days will be spent looking at the stump. His wife, a music teacher, clings to normalcy, “Because that’s what life does, it goes right on having accordion lessons in spite of us.” That “in spite of us” is the whole tragedy, these flesh and bones so brittle and frail in the face of all the accidents that could single us out.

You know these guys: the college buddy who whiles away a decade couch-surfing, smoking pot, and talking a big game while getting fired from minimum wage jobs he despises. He wants desperately to change, and you hope to God he can, but you can see in his eyes there’s a snowball’s chance he will. Mullins constructs tragedy in the most honest, classical sense: life’s bounteous choice stretches far as the eye can see, but character is fate.

Befitting the high velocity of so much of the work, nearly half the stories contain a road. Bands hit the highway to the next gig. The Winnebago rockets through a barren West. A school bus carries a fourteen-year-old girl to a retreat. A man indulges in an epic bout of road rage. In “Bad Juju, 1989” a couple drives to New Orleans in a last ditch effort to salvage their mangled love. If you’ve somehow escaped the misery of a relationship where basic human exchanges become diseased, let Mullins boil it down, “She can’t even tell him she has to go to the bathroom without pissing him off.” Hell on wheels, indeed.  Three Ways of the Saw contains many satisfactions – beautiful fragments of youth, the skewed perspectives of paranoia, a bachelor’s last will and testament, second person narration that actually works. Like an album etched in memory, these stories and their vivid details keep resurfacing as I walk down wintery sidewalks. In “No Retreat” a 14-year-old girl on a Catholic retreat longs to impress a boy back home with some totem of the forest, “I’ll make his heart pound with mysteries.” Where his characters fail again and again, Matt Mullins succeeds.

Three Ways of the Saw contains many satisfactions – beautiful fragments of youth, the skewed perspectives of paranoia, a bachelor’s last will and testament, second person narration that actually works. Like an album etched in memory, these stories and their vivid details keep resurfacing as I walk down wintery sidewalks. In “No Retreat” a 14-year-old girl on a Catholic retreat longs to impress a boy back home with some totem of the forest, “I’ll make his heart pound with mysteries.” Where his characters fail again and again, Matt Mullins succeeds.

Further Links & Resources

- In addition to his life of writing, Matt Mullins is a musician, experimental filmmaker and multimedia artist (which all make quite a bit of sense when you’ve read the collection). You can find some of his interactive works of digital literature (like the haunting “Highway Coda”) at lit-digital.com

- On the site for Three Ways of the Saw, Mullins has posted some excerpts from many of the stories – lots of them – and these paragraphs feel like the self-blurb equivalent of Chris Van Allsburg’s all-time classic The Mysteries of Harris Burdick. Go read them, you’ll get sucked right in.

- Mull: Mullins’s occasionally-updated blog.