When a book promises The Unthinkable, and the reader picks up that book, it automatically becomes the reader’s job to think about The Unthinkable all the way to the end, even if The Unthinkable is strangely never really mentioned again.

When a book promises The Unthinkable, and the reader picks up that book, it automatically becomes the reader’s job to think about The Unthinkable all the way to the end, even if The Unthinkable is strangely never really mentioned again.

After The Unthinkable happened to my family, the last thing I wanted to do was think about it. And if we can’t even think it, why read or talk about it? One can find a lot of comfort in the well-lighted inconsequential narratives of sitcoms, one risks becoming bored and unmoved and almost irritated by The Unthinkable happening to anybody else, irritated by the loud cries and piercing melancholy of Ordinary People.

Because when you have your own grief, why bother with portraits of other people’s inconsolable grief, their rawness suddenly so predictable, so contrived in its loudness? Is grief a story? Or is it simply just, grief?

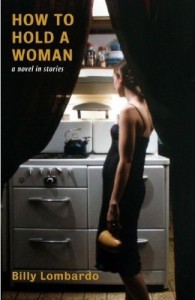

I offer this to explain the degree of skepticism I had approaching How to Hold a Woman (OV Books), a novel-in-stories by Billy Lombardo, about the disappearance of Isabel, the eldest daughter in a family of five. My skepticism started with the title, and ended on page two, as it was clear that this was going to be much more than a study of grief or a psychological examination of a family unit in crisis.

The first story in this novel, “At Khyber Pass,” opens in the father Alan’s point of view, as he waits for his family to pick him at the airport, having just returned home from a two month-long research trip in Madagascar. Alan stands with his bags and wonders if Audrey, his wife, will have cut her hair short or kept it long. He wonders how she will kiss him when she sees him, “so much in that first kiss home,” Lombardo writes. Lombardo creates a welcoming giddiness in these first few pages, a kind of nervous anticipation, as though Alan is a kid waiting for the bus on this first day of school. He also creates a sense of dread, as we know The Unthinkable is approaching. Will they ever get there? They do. Alan finds his wife’s

kiss “full and soft.” Now, they are a happy family of five on the highway, Audrey is talking and changing lanes at the same time; Alan is explaining a kind of tree he studied in Madagascar to his interested children, and we the reader can hardly bear the suspense because we know that The Unthinkable always happens to the family when they are feeling extreme amounts of joy.

But all is well in this first story. They make it safely to Khyber Pass (“the welcome home restaurant”), where Alan realizes over his meal that even though he had only been gone for two months, two months is an entire summer for his children. Summer is long enough for his daughter Isabel to have grown into a woman. Alan is surprised by “the fullness of her hug” and the “strap and clasp of a bra” on her back. “How many songs are written in a summer?” Alan wonders.

Already, Lombardo is showing us how absence can mean different things to different members of the family. Two months is long enough for Audrey to have felt abandoned by her husband, but seems to be nothing to the five-year old Sammy in the backseat, who does not even register that Alan’s absence has been significant. “Dad my ears popped when you slammed the trunk,” was his first line to his father.

And then the best thing happens. Alan begins to cry at the restaurant. In narratives about family tragedy, it is a rare delight to have a writer remind us that strong emotions can be present even before The Unthinkable, that there is extreme love being shared and lost moment upon moment. Alan sits at the dinner table and cries out of love for his family before him:

At Khyber Pass, while Audrey begins to eat, while Sammy sees to the compartmentalization of his food, while Isabel falls in love with the word couscous, while Dex takes infield practice for rookie baseball, Alan begins to cry. It is tearless, mostly. A small wetness at the edge of his eyes, like the tears of a yawn.

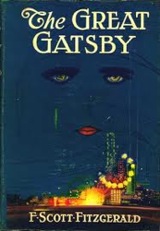

An unexpected kind of darkness soon weaves its way into this dinner scene. Isabel, whose quoting of The Great Gatsby seemed endearing at the start of the story, is suddenly unsettling—over the summer she has become a girl who puts her brother’s needs before her own, a girl who says “So” and never finishes her sentences, a girl who seems to be flirting for her father’s attention. Isabel closes “At Khyber Pass” by quoting Daisy Buchanan (who has been brought up so many times during conversation, the reader is forced to remember what Daisy Buchanan was really like beyond her charms).

An unexpected kind of darkness soon weaves its way into this dinner scene. Isabel, whose quoting of The Great Gatsby seemed endearing at the start of the story, is suddenly unsettling—over the summer she has become a girl who puts her brother’s needs before her own, a girl who says “So” and never finishes her sentences, a girl who seems to be flirting for her father’s attention. Isabel closes “At Khyber Pass” by quoting Daisy Buchanan (who has been brought up so many times during conversation, the reader is forced to remember what Daisy Buchanan was really like beyond her charms).

Lombardo ends this story with Isabel’s last line: “If you want to kiss me any time during the evening, just let me know,” she says to her father Alan. And thus begins the white space, the eerie, unstated absence of Isabel.

If “At Khyber Pass” can be said to be a story of familial happiness, then what follows next, “How I Knew You Were Mad At Me,” is a story of anger, and yet, strangely, a story without dialogue. It is told in the first person by Alan, directed at Audrey. He lays out his observations of Audrey’s unexplained rage with the precision of a legal brief:

The kicker, though, was that there was sour cream in the refrigerator and you never allowed sour cream in the house unless you were going to make potato pancakes, because for some reason you hated sour cream—the color and the texture—makes you sick, and this was supposed to be some kind of proof to me or something, that you allowed sour cream in the house on Father’s Day.

Alan continues the story detailing his allegations against his wife: “You brought your napkin and fork for breakfast but I had already set the table.” There is a youthful voice at play here, and while the contest is dark, and the characters are isolated, it is one of the more spirited stories in the book. The voice, piercing and active, keeps the reader company, though the characters remain lonely and passive. And why are they so lonely and passive? What happened? Why is Isabel not at breakfast with them?

The Unthinkable happened and we seemed to have missed it. Isabel is just not mentioned in this story. Her two brothers are present, but she is not, and we are led to believe that her absence is the reason the whole family dynamic has changed, but of course, this is only speculation. Here, Lombardo courageously defies the standard “if there is something worth seeing, put it on the page,” mantra of fiction workshops. His choice to keep the events surrounding Isabel’s disappearance so off-page that her name is barely even mentioned drives much of the suspense throughout the book. Lombardo does not rely on the shock value of The Unthinkable to keep the reader interested. The stories that follow become not solely about the pain the family experiences, but more about when and how they feel happiness in light of the tragedy. The brothers were so young, and they still

need to do everyday things, like go to baseball practice and play video games and laugh and make fun of their parents. Alan is still a man, and he still gets aroused. And while Audrey has retreated from him, in “The White Rose of Chicago” Audrey finds a sense of community in a bus full of strangers, the first moment we really get to see Audrey do something. And of course, there always remains the underlying tension of The Unthinkable, none of them admit what happened aloud or say Isabel’s name to each other. That is the beauty of How to Hold a Woman. Here are characters trying to admit something, characters struggling to confess and blame someone all at the same time, characters not knowing exactly how they’ve hurt each other, or what went wrong, and where.

As Alan struggles to understand his changing relationship with his wife, Audrey begins to find her own voice, though the catalyst for this emergence remains unclear. Was Audrey simply not present, as Alan portrays her in the first two stories, not even looking at her sons or Alan over the breakfast table? Or did she just not have the space and time that Alan was given by the author in the first two stories of the book? Either way, in “The Business of Night,” we finally get to hear Audrey’s thoughts. We see that she isn’t as angry at Alan – as he thinks she is. Rather, under Alan’s gaze Audrey becomes uncomfortable and sad. She feels like an outsider in her own family, as though “there are boys and there is a woman,” Lombardo writes. For the reader, privy to moments alone with each character, the dramatic irony builds as we learn that Audrey is capable of communing,

desirous of intimacy. In “The Business of Night,” she walks into her husband’s bedroom while he sleeps, as a way to reach out to him, but does not touch him or even get on the bed. She slowly undresses in front of his mirror, and stands there feeling her hips and recalling the birth of her children, wondering how it was possible that her children “spelled words now, they refused assistance, and they had come from inside her.” The prose aches here with longing, and the reader finally, joyfully, gets to see Audrey want. We see her as she sees herself, and not through Alan’s eyes anymore, which, we learn, might have been clouded by his own grief.

Lombardo switches point of view from third person, to second person, to first person, to a story of unanswered emails, and he does this so well, it is tempting to describe the transitions as “seamless.” But the gaps between stories—the years, the POV shifts, the form breaks—are not seamless; they are quite perceptible in fact. And this is mostly exciting. It takes about a page to figure out which family member is telling what particular story and why they are telling it the way they are telling it. But as each new story succeeds, Lombardo builds trust with the reader. Lombardo’s not just imposing a form on How to Hold a Woman for creativity’s sake; the story naturally gives rise to each form. For example, in “A List of the Dead” Audrey writes a series of unanswered emails to Alan, the most obvious formal break. This succeeds because by the end of the book, the reader craves Audrey’s voice. Until that point, Audrey had no response to rival the strength of Alan’s voice in “How I Knew You Were Mad at Me,” and that is exactly what those emails allow her.

In How to Hold a Woman, Lombardo slowly reveals the exact details of The Unthinkable. The narrative attention shifts back and forth between the two surviving boys, and Alan and Audrey’s relationship. For being only one hundred and fifty-eight pages, the novel is impressive in its scope, leaving the reader exhausted, but in the best way possible, as though one has survived something too, like a castaway on a journey that belongs to someone else, one that tires the body, tests the character and confounds the heart. Because sometimes after The Unthinkable, it’s not just sad—it’s confusing too. Parents can feel moments of true happiness, and a family can feel whole again, even if a member is missing, even if only for a moment. The grief is so real in Lombardo’s writing, in the wonderfully complicated way of actual loss. Grief is as raw and beautiful and divisive as a land mass here, at times making it feel like the family members are separated by sea or by war, and nobody can rest, not even the reader, until the characters have found a way home.