Sitting down to write about Jennifer Weiner’s Certain Girls (Simon & Schuster, 2008), I keep thinking of this apocryphal story about a friend of my boyfriend. She wrote a chick lit novel–a seemingly successful one–so that she could sign a contract and pave the way for her “real” fiction–presumably with an advance, rent money in her pocket, a ready-and-willing agent, a publisher with whom she already had a positive relationship. Every writer’s dream, right? The book came out as a trade paperback with Warhol-esque lips on the cover and the word “kissing” in the title.

Sitting down to write about Jennifer Weiner’s Certain Girls (Simon & Schuster, 2008), I keep thinking of this apocryphal story about a friend of my boyfriend. She wrote a chick lit novel–a seemingly successful one–so that she could sign a contract and pave the way for her “real” fiction–presumably with an advance, rent money in her pocket, a ready-and-willing agent, a publisher with whom she already had a positive relationship. Every writer’s dream, right? The book came out as a trade paperback with Warhol-esque lips on the cover and the word “kissing” in the title.

So, why wasn’t that novel real?

I don’t have an answer to that question. I did have another draft of this piece that talked its way around three or four potential answers, but none of them made any sense, and all of them revealed only that I don’t read enough so-called chick lit to do the question justice in the first place. Author Joanna Trollope did a much better job defending the genre in the Guardian.

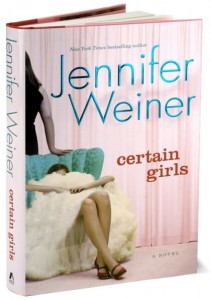

In any case, Weiner wouldn’t be crazy about this conversation. Her newest book is plenty real, and the bestselling author has emerged as something of a spokesperson for her genre. Certain Girls is a sequel to her first novel, Good in Bed, and it takes readers back to her first heroine, Candace Shapiro, a decade after last seeing the plus-sized protagonist.

Weiner addresses some writerly topics in Certain Girls. The main character, a semi-autobiographical version of Weiner, is also a writer: Cannie (now Candace Shapiro Krushelevansky) has been penning pseudonymous sci-fi serial novels with a feminist heroine named Lyla Dare ever since her first book, Big Girls Don’t Cry, hit bestseller lists a decade ago. Cannie’s 13-year-old daughter–who had just been born at the end of Good in Bed–reads Big Girls and is properly horrified at the semi-autobiographical stories about her mother’s sex life and conflicted feelings about having a baby.

A pretty clear line connects the book with Weiner’s life. Someday, undoubtedly, one or both of Weiner’s daughters will do the same thing with her first book, which inspired women all over the world to sing her praises in dozens of languages. And although the sex in her real-life book isn’t so graphic and the embarrassment wouldn’t be so acute, it’s not much of a stretch to imagine the author working through some of this with Certain Girls.

The book is unmistakably chick lit — but so much of the label boils down to marketing. Weiner gets that. In her words, from a Goodreads interview:

The decisions about what kind of cover your book’s going to have, how it gets marketed and shelved in the bookstores, how it’s described by the sales reps and the buyers… all of this is outside of the writer’s control, and, I think, very little of it matters to the reader who just wants a good, engaging, entertaining story and doesn’t really care what color’s on the cover or how dismissive the critics can be.

So… is the label derogatory or a badge of honor? Depends on who’s using it. When writers who are published by imprints like Kensington or the Five Spot or Strapless or Red Dress Ink say they’re writing chick lit, they’re not being derogatory at all. When the Times or the New Republic sneers about trashy, girlie beach-ready chick lit, you can bet that they are. As for me, I try to write the kind of books I want to write, the kind my readers seem to like, and try not to worry too much about what they’re labeled, because as long as they’re being read, I’m happy.

Can those of us trying to write “literary fiction”–an awful name if there ever was one–take a lesson from that as well? The goal for many of us boils down to Weiner’s conclusion: to write something we enjoy, which is in turn read by a lot of people.

If more chick lit was as smart as Weiner’s, the genre’s stigma would probably ease somewhat. Moreover, that stigma seems increasingly irrelevant in a publishing climate like this one. Young women authors shouldn’t have to agree to the pink covers slapped on their books for marketing purposes — god knows, young male authors don’t — but if means your book is winding up in the hands of real live readers, maybe that’s the price you have to pay. It is a price that I personally would be willing to pay, many times over.

For Further Reading

– From Weiner’s own blog, a discussion of “the Curtis Sittenfeld/Melissa Bank dustup” about book reviews and a response to Sittenfeld’s NY Times review of Bank’s The Wonder Spot

– The author’s now-famous comment on the hazards of wishing you wrote chick lit

– Interviews with Trashionista last April, with Bookslut in 2004.

For Your Viewing Pleasure

Jennifer Weiner talks about the genesis of Certain Girls: