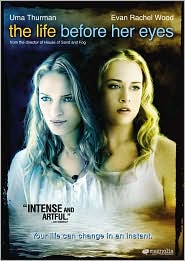

I would have paid good money to get inside Emil Stern’s head while he was writing the screenplay adaptation of Laura Kasischke’s dreamy and lyrical novel The Life Before Her Eyes.

I would have paid good money to get inside Emil Stern’s head while he was writing the screenplay adaptation of Laura Kasischke’s dreamy and lyrical novel The Life Before Her Eyes.

To clarify—I don’t care so much about how he actually wrote the thing (blasphemy?!), but how he saw it, because the novel is largely about how we see in the present and project into the future, how the way we see ourselves affects those and the world around, and before, us. Stern and director Vadil Perelman had what appeared to be an inspiring task before them, then, in adapting the novel: How to turn an image-driven, lyrical novel into a lyrical, visual narrative?

In the book, it’s not hard to imagine the life before its main character Diana’s eyes, as Kasischke’s nuanced prose shimmers with mystery and rot in its perpetual summer. Image is almost another character. Kasischke virtually paints each scene, many of which risk melodrama but never succumb to it—because their author is more interested in possibility than definite drama. The novel revolves around a scene of Columbine-like violence in which a gunman forces two teenage girls to choose which will live. The repetition of objects (blood, flowers, insects, cougars, silver bangle bracelets) keeps the reader bound to the story, which alternates between adult Diana’s idyllic-but-disintegrating life and her life as a high-school student and friend to Maureen, the brunette, prim, Christian foil. Kasischke turns a the violent moment into a genuine “what-if” scenario; what if we were forced to choose our life, then condemned to live it just as we projected it (Diana’s fate)? Certainly, the smells and ugly browns would rise to the surface, and Kasischke allows this in her language and characters. Diana and Maureen are so well imagined, in fact, they float off the page and beg for real lives.

We do get living, breathing characters in the film, which is tonally most believable and complex in its opening credits: gorgeous, watery close-ups of flowers in time-lapse bloom and fade. The movie, I’ll admit, is an atmospheric feat in that it feels in some ways so much like the book—at once lush and spare, ripe, daunting, and sad. It even repeats (and zooms in on) the same objects in obvious faithfulness. Uma Thurman plays adult Diana and tries, with sad eyes and slumpy posture, to convey the complication of mid-life superficial perfection (with hunky professor husband and precocious blond daughter in tow). Evan Rachel Wood, who plays young Diana, however, drives the whole machine. Her splendid youth, her gangly limbs, her watery, piercing eyes—when you watch her inhabit the Diana of Kasischke’s imagination, you are transported. Sadly, the scenes around her draw from expected images of contemporary high-school violence; they are both trite and romanticized. There’s the stock scene of grieving, screaming mothers outside the school when the gunshots echo. There are sirens, gushing blood, the slo-mo fall of the beloved biology teacher, all the pandemonium and tears, and later there is the requisite memorial for survivors and the remembered. Unlike the film, Kasischke’s novel, thankfully, resists these stereotypes and over-politicization of this kind of event, eschewing the memorial, the grieving, the caricature. And this is no small feat as she returns to the shooting scene again and again, each time adding or subtracting a snippet of dialogue, a remembered object or gesture. She creates drama through time; she opens a scene and examines each minute detail, as if these smallest atoms and their repercussions are what determine a life. The novel’s Diana is fueled by the accompanying grief of this realization and not, in Perelman’s vision, by mid-life survivor’s guilt

Kasischke’s novel is a dream for film adaptation; there are plot points, well-developed characters, pitch-perfect scenes, simple and textured settings—even a bit of mystery. Something gets lost in translation, though, from novel to film, and the temptation is to blame it on the medium and the inherently more passive role we as watchers play. Kasischke delves headlong into the psychology of imagination and succeeds because we as readers are right alongside her. We are forced into our own interiors by experiencing the deftly created Diana’s melancholy of living the pre-imagined and plotted life. It is the filmmaker’s responsibility, then, to translate this abstract interior world into a series of images. Perelman does try—that much is clear in the beautiful and stylized imagery and camera work. Without Diana’s convincing interiority behind this gorgeousness, though, the film feels superficial.

The climax takes place in the school bathroom where Diana and Maureen primp before a mirror “clean as a thought in the mind of a god. A thought cast by the creator of everything onto perfectly calm water.” Arguably, this is what we do when we write; we cast a thought onto perfectly calm water. And then the water gushes forth (in this instance, thanks to a classmate with a gun). It’s an age-old catalyst, and brave writers/filmmakers/actors risk getting swept away in such a flood. In this instance, both Kasischke and Perelman ask the good questions about living the reflective life. In the end, Kasischke’s interior realm of complication and inquiry (A-) clearly trumps Stern and Perelman’s visual efforts (C).