I. Simon as Fiction Writer

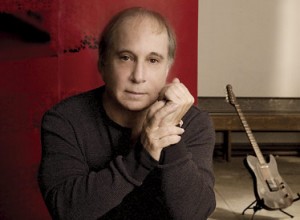

For the last forty-four years, Paul Simon’s lyrics have consistently balanced healthy doses of wisdom and levity, their craftmanship comparable to stories by the most gifted writers of short fiction. I began to think further about the story-ness of Simon’s songs as I was reading Lyrics 1964-2008 (Simon & Schuster, Nov. 2008), the new collection of every word to every song Simon ever wrote. While we may own the lyrics within the CD (or tape or vinyl) jackets, or search online for a remembered phrase every now and then, the publication of this book marks the first time Paul Simon fans can find all of his lyrics in one place.

For the last forty-four years, Paul Simon’s lyrics have consistently balanced healthy doses of wisdom and levity, their craftmanship comparable to stories by the most gifted writers of short fiction. I began to think further about the story-ness of Simon’s songs as I was reading Lyrics 1964-2008 (Simon & Schuster, Nov. 2008), the new collection of every word to every song Simon ever wrote. While we may own the lyrics within the CD (or tape or vinyl) jackets, or search online for a remembered phrase every now and then, the publication of this book marks the first time Paul Simon fans can find all of his lyrics in one place.

These lyrics read like a collection of short-stories, something reminiscent of Grace Paley or Richard Ford. What could be a terrifyingly voluminous book is approachable and enchanting, each song appearing slim and streamlined on the page, thanks in part to Chip Kidd’s outstanding book design.

Since Paul Simon is often touted as a “poet laureate” of his generation, it may seem odd to compare his craft to that of fiction writing. But the lyrics’ understated efficiency, which quickly creates portraits of characters and conflicts, strongly resonates with the fiction writer’s aims. Simon’s lyrics alternate between asking penetrating questions of existence and making deceptively simple and comical rhymes, often within the same song—a tragicomic effect inherent to many contemporary tales.

One song that particularly fits the mold of a bare-bones short story is the zydeco-styled “That Was Your Mother.” The song begins with a father telling his son about the days when he worked as a traveling salesman: “A long time ago, yeah / Before you was born, dude / When I was still single / And life was great.” He tells of a night out in New Orleans. He looks to dance with Cajun girls and listen to music all night long—then he meets a beautiful woman. The father then goes on to say: “Well that was your mother / and that was your father.” But the song moves beyond the merely anecdotal when the father repeats, “Before you was born, dude / When life was great”—a message from father to son that life is really better in one’s youth. “Now,” he tells his son, in a humorous yet revealing epiphany: “You are the burden of my generation / I sure do love you / But let’s get that straight.” As Simon allows the audience to eavesdrop on the conversation, much like short story writers do, we see different sides of the same character, different sides of the same story.

II. The Scenelet

Paul Simon is not a songwriter of the epic, in-your-face-wisdom variety. The vast majority of his songs are not overwritten, or over-symbolized; the songs are collections of small snippets of scenes, or scenelets. These are songs that begin with chance encounters, glimpses of a scene, or eavesdropped moments: “I was having this discussion / In a taxi heading downtown” (“Gumboots”), “I was reading a magazine / And thinking of a rock and roll song” (“The Late Great Johnny Ace”), and of course “I met my old lover / On the street last night (“Still Crazy”). These thoughtful, sometimes whimsical voices or personas speak simply, soberly. Reading each stanza, they don’t appear on the page as vacuous popular sing-a-longs; instead they stand-alone. In the same way a good story or novel doesn’t “sound like literature”—it just has a pleasing voice we find ourselves following—Simon’s songs don’t aim for grandiose messages or try to tell the whole story. The storyteller personas, often troubled and not as stolid or self-pitying as other songwriters’ I’s, will remind readers of some of the best first-person narrators in short fiction.

At his best, Simon seems to write “story-songs”; tightly-crafted narratives, starting at a moment of dramatic action or extreme tenderness that grabs the attention of listeners (or readers). Here is a typical Simon “story-song” opening: “Fat Charlie the archangel walked into the room….” Or “A man walks down the street / he says…” Such immediate connection between an initial idea, some dramatic tension, and an intriguing character also occurs in “Mother and Child Reunion.” (If you’ve ever heard Simon tell the story of where that title came from, it becomes difficult to divorce the actual from the metaphorical, so I’ll not ruin the surprise if you are currently unenlightened about the song’s past.)

III. The “coming-of-age” story

Many writers grapple with the coming-of-age story. Let’s look to Simon to see how he has handled this kind of tale in his songs. From the beginning of his career, Simon’s music and lyrics were concerned with age and aging. In the folksy existentialism of “Leaves That Are Green,” Simon looks to the seasons to see the turning of time, but he also sees his age, in numbers, relentlessly adding up: “I was twenty-one years when I wrote this song / I’m twenty-two now but I won’t be for long.” In “Old Friends” also from the early years of Simon & Garfunkel, the speaker is lost in a moment of imagining a distant, possibly illusory future: “How terribly strange to be seventy.”

Simon revisits the ideas of aging, memory, and time continually through each album, particularly on You’re The One (1999). In “Old,” Simon writes: “I was twelve years old / And the war was cold.” Later in the song, he questions matters of time and magnitude that move beyond the personal and the political: “The human race has walked the earth for 2.7 million / and we estimate the universe about 13-14 billion / when all these numbers tumble into your imagination / consider that the lord was there before creation.” If Simon’s early songs imagined old age, then his later songs are imagining really, really, old age. The brevity of life juxtaposed with eternity is a recurring theme in artistic expression. But that effect of having just read a good story after reading a Paul Simon song often comes about by the structured and stylized way the voice recollects and ponders the narrative. In “How Can You Live in the Northeast?” he writes: “I’ve been given all I wanted / Only three generations off the boat / I have harvested and I have planted / I am wearing my father’s old coat.”

IV. Dialogue

Simon is attentive to the need for dialogue to be both character-building and plot-building. His reliance and fascination with dialogue is prevalent throughout his career. As early as the Simon and Garfunkel album Bookends, Simon uses conversation to heighten the dramatic tension and earnestness of “America”—making this song almost play-like. In “Voices of Old People” on the same album, an experiment in sound rather than a song, Simon introduces tape-recorded voices, aiming to capture people in documentary-style—people as they are. The characters who populate the album’s other songs gain depth, specifically personality and history, through their spoken conversations and realistic-sounding dialogue.

V. Rhyme to find character

Here’s an exercise. Create two characters in five lines of verse that rhyme ABCDB; and then write the story about them that captures and retains the mood of those original five lines. Simon continually creates rhymes that, instead of shouting out to you and hitting you over the head, glisten softly:

Her name was Lorelei

She was his only girl

She called him Speedoo

But his Christian name

Was Mr. Earl

Often these pithy rhymes occur at the introductions to songs, when we first meet characters. Vexed lovers may appear, alternating in appearance between bouts of fitfulness and poise. They are rapidly approaching or about to become enmeshed in a tightly wound knot. In “Was a Sunny Day,” Simon begins: “He was a navy man / Stationed in Newport News / She was a high school beauty queen / With nothing left to lose.” There is a “truth stranger than fiction” vibe to many of these lines. As gorgeous as his simile in “Graceland”—“The Mississippi Delta shining like a national guitar”—the love songs mix poetics with story. These songs have characters with rich personal history and recognizable yet distinct voices. Simon channels what is often the world of autobiography through these songs. The ways in which the pangs of love, along with our memories, interplay is one of Simon’s most frequent storytelling tropes. And the jazzy chords he uses alongside the words (especially in “Something So Right” and “Still Crazy”) resonate so well, you just have to shake your head no.

But as “Everything About It Is A Love Song” from his fantastic 2006 release Surprise ironically probes, all songs, like stories, do not always have one easy meaning for readers to mine, or one singular purpose. As quickly as a listener labels a story as being about one thing, the song is quickly labeled as something else by another reader. Simon’s love songs don’t always present their characters or the songwriter in a comfort zone—instead he describes realistically vulnerable, flawed, and complex people and personalities (characters who find it exceedingly difficult to ever feel truly satisfied, but are not entirely hopeless) plainly, and as they are.

VI. Metafiction

In one of his most self-conscious acts of storytelling, Paul Simon seeks out the moment where songs begin in “That’s Where I Belong.” He notes that narrative is both mysterious and cyclical: “Every ending a beginning / That’s the way it is / I don’t know why.” In particular, the coming-of-age story plays upon a similar idea—every time one stage ends, another begins; time passes.

Sometimes too, as in fiction, the songwriter’s voice will acknowledge, to a certain extent, the self-conscious act of songwriting. In “Love and Hard Times” Simon writes: “I loved her the first time I saw her / I know that’s an old song-writing cliché / Loved her the first time I saw her / Can’t describe it any other way.” We see some of that coming-of-age, and initiation into music scene/biz within the songs. Over the course of forty-four years of songwriting, we construct Simon’s autobiography by reading the collected lyrics as much or more than Simon did by writing them. We see Paul Simon’s journey, living the life of an entertainer and public performer and people watcher in “Run That Body Down” and “Homeward Bound” and “Bleecker Street,” but we also might imagine that these are our collective journeys—wherever they have taken us and to wherever we might be headed—that are chronicled in the Simon catalog. In “She Moves On” we meet “A sympathetic stranger / [who] Lights a candle in the middle of the night.” The idea of finding one’s way back home, so central a conflict in any story, is reflected in so many Simon songs, most famously, “The Boxer.”

VII: Memory and nostalgia

If Simon’s group of first-person speakers share any quality across the board, it would probably be, above anything else, a soft spot for the past. Regardless of the subject and mood of each particular song, a palpable nostalgia for childhood and for place resides within so many of his words, and also in the music itself. Fiction writers from Dickens to Dybek undoubtedly often look to the same aspects of their lives for inspiration, for raw material. And Simon seeks to achieve in song what many aim to do in stories: recreate a feeling or time or place that we can’t recreate in life. Memory and storytelling combine in his lyrics to glimpses, again scenelets of anecdotes from an earlier time. There is the direct symbolism of the Nikon camera in “Kodachrome” or the backdrop of the school in “Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard” or, in a much more focused form, the music and lyrics to the musical The Capeman.

What stands out more than anything in The Capeman is nostalgia of a specific time period and place—New York in the 1950s—rather than a meditation on a concept (youth, memory, existence, love). Its references to Sal Mineo, evocations of West Side Story, and the influence of Puerto Rican, doo wop, and other musical stylings contribute to its being an earnest love song to New York’s image at that time: city and scene materialize with particularly abundant and significant detail in “Adios Hermanos.” Highlighting a gaping difference between fiction and song, Simon builds scene with musical reminders as well as text, while the fiction writer is left to words and their possibilities alone.

VIII: The universe in a nutshell

In one of my personal favorites from Simon’s songbook, “Rene and Georgette Magritte With Their Dog After The War,” Simon imagines two impressionist painters dancing to 1950s music. Based on a photograph Simon came across, he investigates how music becomes part of our daily lives and part of the fabric of the cosmos. It is a complex premise for a piece of music: a song that seeks to create a portrait of a photograph—which becomes a song about music as much as it is a song about painting. The most important details are here for us: the people, the dog, the nostalgia of the moment (for Simon and the Magrittes), and the ever-present soundtrack of their lives.

What many have responded to, and have come to expect in Simon’s music, and his music to come, is not having the entire story filled in for them. Listening to his music, we do not need lives filled in. Just a few details and a scenelet:

A spiny little island man

Plays a jingling banjo

He’s walking down a dirt road

Carrying his radio

To a river where the water meets the sky

That experience Simon writes about in the excerpt above from “That’s Where I Belong” (1999), one of musical immersion and of daydreaming, is much like the feeling you may get from reading this book. The reader, or more conventionally, the listener will always be given enough, but not too much. There’s room to fill in the rest. Simon’s short story-like snippets—these lyrics—and yes, the music that’s meant to be there too, are a kind of elixir that may boil your creative juices.

Appendix: Folksy Wisdom from Rhymin’ Simon

Advice to writers: “You want to be a writer / but you don’t know how or when / find a quiet place / use a humble pen” (“Hurricane Eyes”)

On the pains of someone stealing your dinner: “My Chow Fun’s gone / Oh, no, no / Oh, no, no”

On the economy: “This is the only life / And that’s worth something / When you think about it / That is worth some money (“The Coast”)

On aging: “God is old / We’re not old / God is old / He made the mold” (“Old”)

On working out: “And I’m tired / Nine hundred sit-ups a day / I’m painting my hair the color of mud—mud, okay?” (“Outrageous”)

On autobiography and song: “Well, I’ll just skip the boring parts / Chapters one, two, three / And get to the place / Where you can read my face and my biography” (“That’s Me”)

On faith: “Faith / faith is an island in the setting sun / But proof, yes/ Proof is the bottom line for everyone” (“Proof”)

On divine intervention: “God and His only son / Paid a courtesy call on Earth” (“Love and Hard Times”)

On the birth of song: “Somewhere in a burst of glory / Sound becomes a song / I’m bound to tell a story / That’s where I belong” (“That’s Where I Belong”)