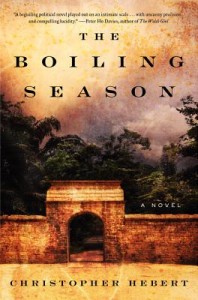

The complex and tragic history of Caribbean tumult is often told in a riotous way that reflects the frenetic rhythms of revolution. However, in Christopher Hebert’s debut novel The Boiling Season, he shows a topsy-turvy world from the perspective of a singularly placid protagonist, Alexandre, who seems impervious to worry. Through Alexandre’s eyes, we experience the ordeal of trying desperately to hold life together while his country goes up in flames. I recently spoke with Hebert about mixing the personal and the political in fiction, and the surprising ways that novels evolve – regardless of how the writer originally imagines they’ll go.

The complex and tragic history of Caribbean tumult is often told in a riotous way that reflects the frenetic rhythms of revolution. However, in Christopher Hebert’s debut novel The Boiling Season, he shows a topsy-turvy world from the perspective of a singularly placid protagonist, Alexandre, who seems impervious to worry. Through Alexandre’s eyes, we experience the ordeal of trying desperately to hold life together while his country goes up in flames. I recently spoke with Hebert about mixing the personal and the political in fiction, and the surprising ways that novels evolve – regardless of how the writer originally imagines they’ll go.

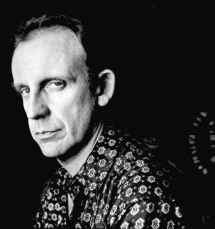

Christopher Hebert graduated from Antioch College, where he also worked at the Antioch Review. He has spent time in Guatemala and taught in Mexico, and he worked as a research assistant to the author Susan Cheever. He earned an MFA from the University of Michigan, where he received the prestigious Hopwood Award for fiction. He is Jack E. Reese Writer-in-Residence at the University of Tennessee Libraries, and lives in Knoxville with his son and his wife, the novelist Margaret Lazarus Dean.

Interview:

Michael Shilling: The Boiling Season brings to mind any number of despotic regimes, but you never mention a specific country. What was the initial impetus for the book?

Christopher Hebert: I’d been working on another project that had political overtones involving a cell of political activists, so I was already interested in the general topic of political violence. Then I read an article in The New York Times called “In Katherine Denham’s Eden, Invaders From Hell.” And it was about a woman in Haiti who owned this land that contained the last bit of untouched tropical rainforest, a kind of preserve, that had been overtaken by squatters who were just trying to survive in this very impoverished country, cutting down trees for shelter and fire, drinking water from the spring, which is totally understandable, yet completely counter to Denham’s interests.

A lot at stake there for these competing interests. Sounds like the start of a plot.

I’ve always been interested in politics, but not any specific incidents as much as people’s desire to engage in a larger struggle. And it turned out, from reading this article, that the home on the land had been the home of General Leclerc, Napoleon’s brother-in-law, who’d been sent to Haiti to quell the slave rebellion during the early 19th Century. This property, in the seventies, had then become a Jet Set resort that Mick Jagger had been involved in financing.

So this story encapsulated many of the struggles and exploitations of Haiti’s history?

It did. And even though I didn’t know much about Haiti when I started, this story, and Haiti’s broader history, became a prism through which I could explore the larger ideas I have been long interested in.

Amazing how the clichés about Colonialism are, well, true. Like, Mick Jagger partying right under the nose of torture.

I recently watched a documentary about the making of this estate where Jagger and company were partying, and the interviewer asks a French PR guy about that [incident]. “You know,” the interviewer says, “to get to the estate people will be driving, in Rolls Royces, though the most impoverished slums in the hemisphere. What about that?” And the Frenchman, who’s dressed in white pants and tan and shirtless, wearing gold chains, says, “That doesn’t matter. These people are poor but they’re not violent. Americans have a word for it – groove. These people are coming here to groove. No big deal.”

On the one hand, that statement is kind of nonsensical. At the same time, what he says well-explains the pathology.

Well, it exposes it but it doesn’t entirely explain it. It’s baffling either way. You can just sense that insanity, that there’s no way this estate, in whatever form, can ever work if it’s surrounded by misery.

So, in telling the story of this insanity and its conflicts, you chose an allegorical approach. There’s no named country in The Boiling Season, and Alexandre operates in a way that some would call passive, and / or oblivious. It’s a daring way to frame the book. When did you zero in on Alexandre?

So, in telling the story of this insanity and its conflicts, you chose an allegorical approach. There’s no named country in The Boiling Season, and Alexandre operates in a way that some would call passive, and / or oblivious. It’s a daring way to frame the book. When did you zero in on Alexandre?

He was always the guy I wanted to focus on. The more I looked into this story, the more I realized that political unrest, even on a massive scale, is just a daily part of people’s lives. And even in that situation, a lot of people are indifferent – few are revolutionaries. They just want to live their lives. So I wanted to explore that indifference, to have the story from the perspective of someone who has his own dreams and is driven by them, and not by the political actions around him.

And in a situation such as Alexandre’s, there’s only so much indifference possible.

Right. There are always going to be forces that are going to pull him back in. In a regime such as the one in the book, no one was ever presumed innocent. But I was fascinated by a character such as Alexandre—who, in a situation like this, would prefer to save the trees instead of the people? What would it mean to make that decision? To disassociate yourself from all that is around you?

What a deliberately aberrative act. You don’t do that unless you have a strong reason, and it’s probably a reason that haunts the hell out of you.

Yes, and I was interested in the obvious conflicts that come out of someone trying to distance himself from all that is happening right in front of him.

You do that with other characters who slam right into Alexandre’s interests. Take Paul, his oldest friend, who just wants to capitalize the situation in any way he can. But just as Alexandre isn’t merely the embodiment of indifference, Paul is more than just greed and enterprise. Same with Alexandre’s father, who, in his Marxist ideals, is a kind of noble dinosaur, or so Alexandre thinks. Did Alexandre start as such an ostensibly passive character?

I had the idea of him that way pretty much from the start. The first scene I wrote is the one, which is quite far into the book, where Alexandre is sitting on the veranda of the manor house, looking out and seeing Dragon Guy, whose M.O. can be pretty much summed up in his name, arriving, and then doing nothing about it. So from the outset, he’s a guy who’s watching over things, and trying, in a passive way, to control the situation without getting sullied.

Well, it worked, because what becomes clear to the reader is that, despite this seemingly passive protagonist, he’s actually quite active. His activeness sneaks up on you in an artful way.

Well, it worked, because what becomes clear to the reader is that, despite this seemingly passive protagonist, he’s actually quite active. His activeness sneaks up on you in an artful way.

Some people have compared Alexandre to the butler in Remains of the Day, but I disagree. The butler is actually passive, where Alexandre is not. He is ambitious in a way that the butler is not. Alexandre wants something and he’s going to work hard to get it, even if it seems like he’s laying back.

A writer doesn’t want the reader to feel that character development is being telegraphed, but you also don’t want them to be needlessly confused. It’s a hard balance, especially with characters lacking self-awareness.

I kind of like characters who are sort of . . . dumb. Often, as like a default, novels have these protagonists who are insightful and know themselves and the world, and I admire writers that richly explore character psychology. But as a writer, I tend to create people who don’t know themselves and the world, and are struggling to make sense of things and are puzzled.

As far as other authors whose books come to mind when reading The Boiling Season, I immediately thought of Madison Smartt Bell. Was he an influence on the book, and if not, who was?

Bell’s books about the history of Haiti and Toussaint Louerverture – such as All Souls’ Rising and Stone That the Builder Refused – are fascinating. While an influence on The Boiling Season, they’re extremely different from it. While I glossed over and compressed a lot of historical events, Bell manages to be both incredibly faithful to the history while also incredibly artful at the same time. I marvel at his ability to bring not just history but also these actual characters to life. As historical fiction, it’s like nothing I’ve really ever seen. I mean, it’s always tricky having these white guys writing about a place like Haiti, but he’s done it in such a way that he’s considered an authority.

Any other major influences?

One that comes to mind is Bel Canto, by Ann Patchett, in that it’s also a political novel stripped of the politics, to sort of humanize the political story.

You mentioned another project at the start of the interview about a political group. Now that you’re done with The Boiling Season, have you gone back to it?

I have. And even though it shares a similar thematic content – in terms of political matters and how people operate within them – it’s entirely different in every other way. It’s set in Detroit in the present day, and each chapter is told from the perspective of a different member of the group, whose stories overlap in a number of ways.

Kind of a Venn Diagram.

Yeah, there’s a lot of “venning.” In that structural way, it’s kind of like A Visit From the Goon Squad. While it’s nice to be with one character for an entire book, and get to know him – that consistency and stability – there’s also something nice about exploring different perspectives all the time via a number of characters.

So a lot of “ensembling,” too?

Indeed.