A few months ago I ordered the second edition of Mary Miller’s Big World (Short Flight/Long Drive Books, 2009) and the publishers, Elizabeth Ellen and Aaron Burch, threw in a galley of Dylan Nice’s debut story collection, Other Kinds (Short Flight/Long Drive Books, 2012). It’s a hot, taut little read with big life, precise writing, and haunting characters. I immediately loved it. But what perhaps struck me first about the collection is that Nice had used a structure similar to the one I’d employed with my newest collection, Vampire Conditions (Holler Presents, 2012). Both books are broken into sections, and each of those sections are preceded by italicized vignettes. I assumed Nice and I had influences in common.

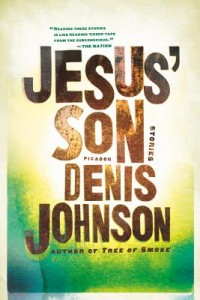

After mentioning these similarities to Burch, he suggested that Nice and I chat about our processes to see if my assumption had been correct. He sent us an introductory e-mail, and we became instant Internet friends. I mailed Nice a copy of Vampire Conditions and what follows is a few weeks worth of us chatting about structure, process and, interestingly, the influence of Jesus’ Son.

Interview:

Brian Allen Carr: I thought heavily of two books when putting together Vampire Conditions. The first was In our Time, by Hemingway, which I imagine you also had near to your heart when forming Other Kinds. The second is …and the earth did not devour him, by Tomas Rivera, which is punctuated, though in a less organized way, with brief vignettes like my collection. My hope was to put together a book that people would not dip into but would rather read cover to cover. Can you talk a little about structural influences and your own hopes for how people might read your book?

Dylan Nice: I definitely wanted to avoid the collection feeling like it was all my stories in a pile, which was probably an unwarranted fear, one that started in the vast imagination of my insecurity. I knew that the stories talked to each other, since they were all of the same world and born of a single vision: a working through of a conflicted self. They were also each about a place and set in that place or about being from that place and set somewhere else. I could feel an arc when I thought about what I knew was going in the collection. The challenge was figuring where that arc started, its course, and what story might swallow the collection whole at the end.

It was pretty apparent from the start that “Flat Land” would be the last story, even though I hadn’t written it yet when I signed the contract with Short Drive/Long Flight and it wasn’t entirely finished until a few weeks before the collection went off to the printer. It was an aftermath story and stubborn and did not want to be beat into shape. I had the last lines finished by the first draft and they did that swallowing I was after. They pushed forward and backward in time.

For the rest of the stories, my first idea was to put them in chronological order (oldest story first and newest story last) and see what that looked like. I figured it would provide the book its own memory to work from, a memory that would accumulate, each story projecting something forward into the collection. This idea held up pretty well, with some minor adjusting.

I thought a lot about Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son while writing the stories and organizing them, how the stories interlink through a common desperation. Things move forward some, but they circle and swirl a lot.

The idea behind the three italicized vignette prologues in Other Kinds was, as you accurately inferred, borrowed from In Our Time. I had these very short pieces I wanted to go into the collection, that seemed vital, but which I was reluctant to give their own title and place in the table of contents. Naming them seemed to ask them to do more work then they were prepared to do. They were nearly cut. But it turned out nicely that once I had my order figured out for the larger nine stories, the collection seemed to have three movements, three sections, and I had three very short pieces that could do their quiet work in the gaps.

The idea behind the three italicized vignette prologues in Other Kinds was, as you accurately inferred, borrowed from In Our Time. I had these very short pieces I wanted to go into the collection, that seemed vital, but which I was reluctant to give their own title and place in the table of contents. Naming them seemed to ask them to do more work then they were prepared to do. They were nearly cut. But it turned out nicely that once I had my order figured out for the larger nine stories, the collection seemed to have three movements, three sections, and I had three very short pieces that could do their quiet work in the gaps.

Could you talk a little bit more about that final story, since you hadn’t written it before you sold the collection? What was the impetus for it? What about it made you know it would be the finale?

After Elizabeth [Ellen] and Aaron [Burch] accepted the collection, I knew there would be a story or two that would end up cut, and the collection would be too thin, both in word count and the total work done by the word count. I wanted the collection to be thin, physically, but fully inhabited, covering a whole movement. I knew that I had most of the collection’s scope finished, but no story in the collection was prepared to bring the “click” at the end. There were one or two which hit the right note but which obviously went somewhere else in the collection or were just plain too short to be the closer.

I needed to draft a hefty story from scratch, but was pretty psychically drained. The fires that burned in the rest of the book were out. Months passed. Then, last winter, I got a solicitation for fiction from a big New York magazine. So I had two pretty good reasons to get to work on a thicker piece of writing, though I didn’t feel I was much of anywhere or had much to say about it. That semester was hazy, blurred at the edges, and I started working at the student computer lab in the main library: a huge, surgically lit room with a few hundred computers manned by ear-budded undergrads. I liked the anonymity there, the feeling of being housed in a massive, glowing hive. The privacy was total.

And so, sitting in the middle of a long row of strangers, I started working on a story set in the space directly following an exhausting fight. I have a terrible imagination. I don’t write well about anything that I’m not currently experiencing. Since it was a listless, amorphous experience I was trying to be precise about, drafting took months, many hours in the main library computer lab. The big New York magazine passed when I submitted it in February, but I appreciated the nudge.

You also mentioned Jesus’ Son. Let’s talk about that book’s influence a bit more, because I’ve been picking it up recently. So many good lines. Gary Lutz blurbed Other Kinds, calling it “a book to be memorized,” and I was curious, Dylan, what your approach is. Are you a sort of sentence-by-sentence guy, the way Lutz explains his writing style. Or are you more like Denis Johnson with Jesus’ Son, the myth being that the stories in that book were these bar rants Johnson knew before he began writing?

The intensity of my sentence fixation varies from piece to piece. In drafting some stories, there’s no immediate need for me to preen over the sentences because there is a strongly felt thing driving the writing and demanding precise arrangements. The strongly felt thing is a helpful condition. It is a powerful arbiter of no and yes. Its exact nature is hard to pin down. It might be fear of death.

When I can’t conjure a strongly felt thing, which is very often, the sentence can serve the opposite function. The sentence can look for it, can probe to legitimize its own existence. I find, though, that these sentences—even after they’ve tapped into something interesting—never feel as alive to me as their channeled cousins. The fakers hide well, but I know who they are.

Both kinds go into all drafts, but some stories are charmed, others cruel. The big trick is fixing it so people can’t tell the difference. I think this is probably Johnson’s biggest feat in Jesus’ Son. Those stories don’t sound like writing. But they totally, totally are.

What about the arrangement of the six stories in Vampire Conditions, Brian? I noticed that the first story, “The Paint from Her Hands,” and the last story, “Everything Will Fall its Way,” seemed to both deal with a similar failure: initiation into parenthood is thwarted, suspended. Meanwhile, the stories in the middle seem to come from narrators a little closer to childhood themselves. Children and lineage seem to be a recurring theme in the book, and I wondered how you thought about them playing out and talking to each other in the arrangement. Was it organic–something bubbled up from your subconscious?

All of the stories in Vampire Conditions show non-traditional fathers with the exception of the vignettes, which are set in Boy’s Town.

The roles are ordered like this: father of an inanimate object, adoptive father, father of a dead son, fill-in father, mythical father figure, imaginary father. In most stories, the father role is central to the story. The dead son’s father was a small role. I suspect this is for personal reasons.

Each story mirrors, in some way, the story in its opposite space. For example, the first and last story are the only ones written in third person.

Aside from that, the organization is a very structural one. Each cycle of stories includes a vignette, a 2,000-word story, and a 5,000-word story. Those aren’t exact word counts, just ballpark figures.

I have a background in journalism, and I actively think about word counts when writing. I think length dictates a kind of restraint. It forces you to explore or confine, depending. A good example of this might be Jean-Christophe Valtat’s 03. It’s an eighty-page novel, which sounds short, but the whole thing takes place in the span of about fifteen minutes as a boy contemplates his love for a retarded girl while standing at a bus stop. Another good example, albeit in the opposite direction, might be “Broke Back Mountain.” 03 could have been four pages long. “Broke Back Mountain” could have been 400. (Dear reader, feel free to substitute The Unnamable and “The Necklace” if you’d rather more canonical examples.)

I’m interested in your use of word counts as a contsraint and how Vampire Condition‘s structure follows a repeating, progressing pattern. Did you give yourself 2,000 and 5,000 word assignments while writing the book? Or come across that idea later? Has the constraint been internalized in your sentence writing, or do you still find you have to watch the meter and be your own police?

The only stories I wrote after fully realizing the structure I was going to use were the vignettes. The others had been written.

When my wife got pregnant, I was really afraid I’d be a shitty father, and I started writing stories about shitty fathers. The first of these stories was “Baby Grand Dangle,” which was in Keyhole and my first book [Short Bus]. But most of my longer stories since then have dealt with that as some topic of issue. I didn’t realize I was doing it until I was going through the last few things I’d written, and it occurred to me I should place them alongside each other and see what could come of it.

I usually start stories with some image, and then I move to find a voice. With “A Brief OK,” I wanted to write about the dedication images people in South Texas put on the back windows of their cars. With “The First Henley,” I wanted to write about a one-fingered gun fighter.

I don’t think about sentences so much. The only time sentences are lonely places is if they’re precious like a brand new doll that a human child hasn’t loved a soul into. Voice carries soul. That’s my idea of it.

I’m a great fan of classic stories. O. Henry. Maupassant. The Brothers Grimm. Hans Christian Andersen. Nathaniel Hawthorne. Edgar Allen Poe. I enjoy stories that can be quickly told—reduced to their spirit and re-imagined in a bedroom as oral bedtime tales. The older my daughter gets, the greater the fan I am of this idea. Phillip Pullman just put out a new translation of Fairy Tales From the Brothers Grimm that is remarkable. Italo Calvino has an awesome collection of fairy tales. Ben Loory has done a remarkable job of repurposing the fairy tale in his book, Stories for Nighttime and Some for the Day.

We’ve been talking about Jesus’ Son quite a bit, so I’ll pause here to say a few things about why I believe that book is brilliant:

1. The plots of the stories are so true that they can be repurposed—evidenced in the film translation.

2. The sentences of the book are so strong they can be underlined, used as epitaphs or mottos.

3. The book can be read as a novel.

4. The book can be read as a collection.

5. It does all of these things in like 150 pages; it didn’t need the 300 or so Johnson told his publisher it would take.

I always have to find the voice before I think about the word count, but I usually know the voice after I’ve configured the first thoughts. I might redraft the first page or so of a story a hundred times, but once the voice is confident (and by confidence here I’m referring to the voice rather than the narrator), I generally only write one draft of a story. I’ll edit, but I rarely redraft.

I generally tell myself the word count by the end of the first paragraph. I’m not very exact in this. I’ll say, “about 2,000 words.” I don’t always stick to it, but, by deciding early, I’m basically telling myself how many adventures my characters can go on. How graphic the fight scenes. The voice, of course, is a big part of this. I ask questions like: if this voice were to be arrested, what would it tell us of the experience?

That kind of stuff.

Tell me your three favorite sentences from Jesus’ Son. It’ll be like our happy birthday to the book.

Great idea, but I’m going to cheat and use passages for two of mine:

It was raining. Gigantic ferns leaned over us. The forest drifted down a hill. I could hear a creek rushing among rocks. And you, you ridiculous people, you expect me to help you.

This is a gimme, probably one of the most famous moments in the book, but what I love here is the staggering, swift turn from addict to messiah. The images come in flashes: a kind of garden. We’ve traveled someplace essential and mysterious. It appeals to those Christian notions which permeated me deeply during my childhood: the idea that perfect weakness somehow becomes perfect strength.

A clattering sound was tearing up my head as I staggered upright and opened the door on a vision I will never see again: Where are my women now, with their sweet wet words and ways, and the miraculous balls of hail popping in a green translucence in the yards?

There’s a kind of car crash caliber violence throughout the book. Nothing is secure, objects drift past us, even time is sliding, tumbling in from all directions. Maybe we’re asleep on a train, or somewhere in the mountains. It’s too much context, really, that kills images. It turns glowing hail into weather, restoring warmth into relationship.

People entering the bars on First Avenue gave up their bodies. Then only the demons inhabiting us could be seen. Souls who had wronged each other were brought together here. The rapist met his victim, the jilted child discovered its mother. But nothing could be healed, the mirror was a knife dividing everything from itself, tears of false fellowship dripped on the bar. And what are you going to do to me now? With what, exactly, would you expect to frighten me?

Ok, I’ll just be on my way then, if that’s the case.

Links and Resources:

- Read Dylan Nice’s story “5/24/2010” at Wag’s Review.

- Check out his Rumpus essay on Orwell’s role in his development.

- From the Texas Observer, read Brian Allen Carr’s story “The First Henley” and his interview on Vampire Conditions and being from Texas.

- For more on the influence of Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son, here’s the paean Jeffrey Eugenides wrote for Salon.

- Visit the Hobart Website to pick up a copy of the newest issue (December 2012), subscribe to the journal, or check out their Web exclusives.