In the traditional Buddhist formulation, suffering flows from desire. The Four Noble Truths teach us as follows: suffering exists in the world; this suffering exists because we are attached to our desires; if we can loosen our attachment, our suffering will cease; and we can loosen these attachments by traveling on the Eightfold Path. This is a beautiful idea, well worth considering for our daily lives, whether we are Buddhists or not.

In the traditional Buddhist formulation, suffering flows from desire. The Four Noble Truths teach us as follows: suffering exists in the world; this suffering exists because we are attached to our desires; if we can loosen our attachment, our suffering will cease; and we can loosen these attachments by traveling on the Eightfold Path. This is a beautiful idea, well worth considering for our daily lives, whether we are Buddhists or not.

But this kind of enlightenment would be terrible for our fiction.

Plot development and character development are both inextricably linked to desire. What would we do without it? Without desire, characters become static and uninteresting, and our plots stall. Without desire, what would move our stories forward? And why would we keep reading?

Here, then, with all due respect to the many Buddhist traditions, are the Four Noble Truths of Fiction Writing:

- Fiction is grounded by suffering; suffering creates a tangible, deeply felt reality for the characters to inhabit.

- Fiction thrives on attachment: the attachment of characters to their world, and their desperate desire to make changes in their worlds.

- Desire tightens the story’s hold on characters, motivating them to action sentence by sentence.

- A successful plot is built on an increasing level of desire, which pushes characters through a world (creating plot) while giving the writer space to explore and deepen the characters’ relationships to the narrative space and to each other.

The playwright David Mamet, in his David Mamet way, has put it even more simply and ruthlessly in an interview on NPR’s Fresh Air: “The essence of drama is that a character wants something desperately. The audience will watch to see if he or she gets it.”

Mamet’s idea is not exactly new. Most writing teachers ask, “What does your character want?” And: “What’s standing in their way?” This is the standard desire/obstacle formula, the basis of, well, every plot in the world. But Mamet’s idea, and its Buddhist parallel, contains an element that we sometimes overlook when we construct a typical desire/obstacle situation, especially in early drafts of our work.

Note that Mamet does not just say that ‘the essence of drama is that a character wants something.’ To generate the kind of heat that compels a reader to keep reading, the character must want something desperately. That extra word makes a big difference. Compare the following statements. “I want a piece of chocolate.” And, “I desperately want a piece of chocolate.” The first statement is flat: I want, yes, but not in a very compelling way. You want a piece of chocolate. So what? Join the club.

The second, however—well, you can already feel the questions it generates. “I desperately want a piece of chocolate.” Why? What happened to you that you need it so badly? And what will you do to get it? It has heat, and even more, it can lead to many different plot possibilities. This is what Buddhism sometimes calls craving, the step after desire that leads to suffering. And thus to compelling fiction.

This feeling is apparent in the classic Joyce Carol Oates story “The Tryst.” The plot, at first glance, is unsurprising. A successful suburban family man is having an affair. His mistress makes his life feel exciting and full. “He was one of the adults of the world now,” Oates writes. “He was in charge of the world.” His twin desires—for a secure family life on the one hand, and for excitement on the other—seem to be equally fulfilled. “He thought of her, raking leaves,” Oates continues. “A lawn crew serviced [his] immense lawn but he sometimes raked leaves on the weekend, for the pleasure of it. He worked until his arm and shoulder muscles ached. Remarkable, he thought. Life, living. In this body. Now.”

But security and excitement are difficult desires to balance, and his mistress has her own desires as well, which complicate matters even further. The man ups the ante (of course he does, because he craves her, her attention, her admiration, in ever more exciting circumstances) by bringing her into his home while the family is out. After their latest tryst, in the bedroom he shares with his wife, the woman enters the bathroom and refuses to come out. Suddenly the man’s conflicting desire kicks in—self-preservation, protecting what he has—and the story turns in a wonderfully dramatic but completely believable way:

He tried to fight his panic. He knew, he knew. Must get the bitch out of there. Out of the house. He knew. But if he smashed the paneling on the door?—how could he explain it? He began to plead with her…please be good, be good, don’t make trouble….why did she want to worry him? Why did she want to ruin everything?

Oates constructs the situation beautifully—the self-image the man wants so desperately versus the woman he desires so desperately—and brings them into direct conflict. These are two opposed cravings, one representing status, the other representing physical pleasure. Together, they are wonderfully combustible.

When we encounter these powerful desires in work by accomplished writers such as Joyce Carol Oates, it can seem a work of miracles or of genius. But we too can train ourselves to be more attentive to our characters’ desires. For my process, I’ve learned this best happens during revision. Over time I have learned to remind myself, as I rewrite, to try to increase the level of craving my characters feel, which can dial up the intensity and lead to a more satisfying next draft.

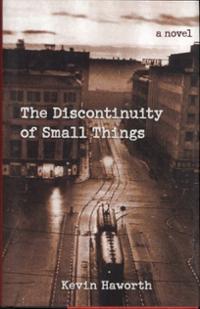

I went through this process many times, with many false starts and rewrites, with The Discontinuity of Small Things, my first book, which took almost eight years to finish. The novel is set in Denmark during the German occupation and the main action takes place from 1940-1943. The main characters are, briefly: Bakman, a Danish medical student and reluctant member of the Resistance; Hannah, a Jewish university student with a secret life as a member of a Zionist cell; Carl, a struggling fisherman in a northern village; and the Faroe Islander, a mysterious character who is never clearly named and never speaks but was enormously fun to write.

I had a lot of difficulty plotting the book. I was juggling multiple characters who had very different relationships to the German occupation, and I was working within the constraints of history. The broad arc of the plot follows the history of the occupation, from the German invasion in 1940 to the escape of most of the Danish Jewish population to Sweden over the course of just a couple of weeks in October 1943. Staying within this historical arc gave me a beginning and an end; but developing the middle required a lot of thinking not just about plot, but about what my characters desperately desired in their actions.

I had a lot of difficulty plotting the book. I was juggling multiple characters who had very different relationships to the German occupation, and I was working within the constraints of history. The broad arc of the plot follows the history of the occupation, from the German invasion in 1940 to the escape of most of the Danish Jewish population to Sweden over the course of just a couple of weeks in October 1943. Staying within this historical arc gave me a beginning and an end; but developing the middle required a lot of thinking not just about plot, but about what my characters desperately desired in their actions.

Along the way, I learned that, as for most writers, there will be a few times when you simply need to get a character from place A to place B. My friend and teacher Ron Carlson calls this “the mattress problem,” because as he describes in his book on writing Ron Carlson Writes a Story, he once addressed this issue by putting a mattress on the back of his character’s truck and then having said mattress fly off an interstate and land forty feet below on a city street. In my case, I slowly realized that I needed one of my characters, Jette, wife of the fisherman Carl, to return from Copenhagen to their fishing village home of Gilleje. This was a journey a person was not likely to take in the midst of war. She had an important part to play in the final scenes of the book, I imagined—but first she had to get herself there.

And here we get back to desire. How powerfully it can work, together with plot, as an engine for our writing. Jette had left the fishing village, and left her husband too, because their desires no longer ran together. In Copenhagen, Jette reveled in her new anonymity; there she was not a barren wife of a struggling fisherman. At first, I considered having Jette just return to her husband; that would have served the plot, at least superficially. But that felt false to me; while she still loved him, she certainly did not have a desperate need to return to him. For her to make such a significant change, to reverse course at this late point, I had to find something else.

Early in the novel, I had referred to a series of miscarriages that had led Jette and her husband to give up the possibility of children. I sensed the loss of those possible children as a kind of craving that could not be fulfilled. Together with Jette’s contact with Copenhagen’s Jewish population, this awakens a new desire; she is, at core, a person of purpose and responsibility. When she realizes the obstacles to the Jews’ escape, she boards the train back to the village. I wrote:

She will go to Gilleleje and wait for the Jews to come. And when they do, she will say to one of them: give me your child. If they catch you, your child will be safe. You could drown or get shot or travel all the way to Sweden just to be sent back. Then what would happen to your baby? She will say it plainly to these Jews, so that they understand the risks. Then they will see the value of giving their child to her….

This plan—an ad hoc adoption of a Jewish baby—is certainly nothing Jette would have contemplated at the beginning of the book. And it is not entirely rational or even likely. But it is born of a powerful desire to be needed and to care for someone. Jette’s motivation here, I came to understand, is complex; it contains elements of suffering and desperation, and rooted in a fierce attachment to her world.

When a plot problem becomes an opportunity to explore a character’s desires, the fiction benefits. Jette grew into a much deeper, more central character. In some ways, she’s the emotional core of the last sixty pages or so. This happened, in part, because “I need to get her on a train” (a plot problem) became “What does she want that might get her on that train?” (an investigation of my characters’ desires).

While we’re on the subject of Jews, rather than Buddhists: There is a story that begins in ancient Babylon and continues hundreds of years later in Medieval Spain, and it is one of our oldest stories about desire. In the pages of the Babylonian Talmud, three rabbis disagree about what fruit actually hangs from the Tree of Knowledge. (One thing they all agree on: it’s not an apple.) Rabbi Meir says that fruit is actually a grapevine, because it led to sorrow: as the Ladino proverb tells us, no ay koza ke trae yoro al mundo kuanto el vino—nothing makes the world cry more than wine. Rabbi Nehemiah, on the other hand, says it was a fig tree, because after Adam and Eve ate this fruit, they saw they were naked, and grabbed the nearest leaves to cover themselves. Rabbi Judah disagreed with both of them, and claimed it was the humble wheat stalk, born of our basic desire for food.

Seven hundred years later, Maimonides, a 12th century rabbi and physician, has a different reading. He claims that the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge is the etrog, a lemon-like object with a beautiful yellow color and a sour taste. The etrog was lovely to behold; they wanted to pick it and hold it; they wanted to taste it, never realizing that its sour flavor would be at odds with its gorgeous appearance. Before this moment, all their desires had been fulfilled easily. Experiencing the Tree of Knowledge means knowing the sensation of unfulfilled desire. The path from innocence to experience, per William Blake, is the path of desire. Desire crashed us out of paradise and, perhaps, to an even greater place.

Even His Holiness the Dalai Lama teaches us this notion, saying, “Without desire, how can we live our life? Without desire, how can we achieve Buddhahood?”

The moments where our characters explore our highest aspirations make them part of literature. When they reflect our deepest cravings they are just like us.