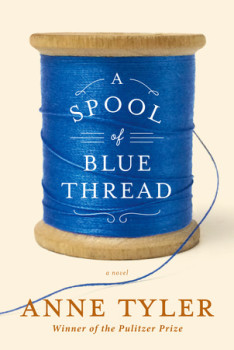

Novelist Anne Tyler is famously publicity averse, rather like one of her own reticent characters. But she’s been on the circuit more since the release of The Beginner’s Goodbye (2012) and the recent publication of her twentieth novel, A Spool of Blue Thread, which is just out from Knopf. She recognizes, as she told Diane Rehm earlier this month in her first live radio interview in her fifty-year career, the “book world is very different now,” and there is a need to be more direct. Nevertheless, she still firmly maintains that her own life is un-interesting. Asked recently by the New York Times who her preferred biographer would be, she replied, “No one! Like most writers, I have led a life so nearly eventless that even my biographer would nod off in the middle of it, let alone my readers.” Really? She grew up on a series of communes, and chose to study Russian Literature at Columbia because “that was one of the most outrageous things you could do in America in the 1950’s,” she told The Guardian back in 2012.

Yet even if her life is as snooze-worthy as she asserts, Tyler demonstrates with her work that, through the eyes of the canny beholder and the words of the gifted story-teller, ordinary details of daily life become revelatory and intriguing. Throughout her career she has studied and chronicled family life from the inside, most often in Baltimore neighborhoods near where she raised her own family and still resides. Some fault her for sentiment or repetition, some find her characters too similarly marked by eccentricities of behavior and occupation. But others, like myself, believe authentic sentiment gets a bad rap, and recognize her people. Behind the public curtains, whose family, what profession, isn’t a little odd?

But although it is a recent pleasure to hear and read her observations about her work (and occasionally, her life), I suspect her bumper sticker might read, “I’d rather be writing.” Whether her publicity-avoidance bespeaks shyness, modesty, or a taste for privacy, she doubtless requires time to work, to keep her focus (and our focus) on the stories of her characters: families created by birth, fate, and accident. In the aforementioned Guardian interview, Tyler has said that for her heaven is to be in the middle of a novel. To prolong that celestial state, she wanted to write a long, multi-generational family epic. She intended to work her way backward from the present through all the antecedent generations so she would never come to an end, never finish writing, always be in the middle of the book.

A Spool of Blue Thread is that novel, the story of the Whitshank family. But Tyler discovered, as she recently told Rehm, that after three generations she wasn’t interested in the Whitshanks’ earlier forbears. So she finished this novel and went on to her next—which is fortunate for those of us who deem it heaven on earth (or pretty close) to be in the middle of reading a Tyler novel. Last weekend en route from Washington to New Jersey for a family wedding, I settled into the passenger seat and read my way north. (I glanced up from A Spool of Blue Thread as we passed through Baltimore.) Anne Tyler’s wise, generous perceptions about family lingered with me during our own family festivities. On the way home I finished the book, and began re-reading.

A Spool of Blue Thread is that novel, the story of the Whitshank family. But Tyler discovered, as she recently told Rehm, that after three generations she wasn’t interested in the Whitshanks’ earlier forbears. So she finished this novel and went on to her next—which is fortunate for those of us who deem it heaven on earth (or pretty close) to be in the middle of reading a Tyler novel. Last weekend en route from Washington to New Jersey for a family wedding, I settled into the passenger seat and read my way north. (I glanced up from A Spool of Blue Thread as we passed through Baltimore.) Anne Tyler’s wise, generous perceptions about family lingered with me during our own family festivities. On the way home I finished the book, and began re-reading.

Abby and Red Whitshank, in their mid-seventies when the book begins in 2012, live in a capacious, welcoming house in a comfortable neighborhood in Baltimore. Red’s father Junior built the house. “So there was Red in the house he grew up in and where he planned to die…not much of a story in that,” Red muses as the book opens. He (Tyler-like) considers his own life story dull. By the second chapter, readers begin to discover just how wrong he is as Tyler introduces the two “defining” Whitshank family stories

The Whitshank creation myth concerns how Red’s father Junior “fell in love with a house”–Red’s current house on Bouton Road. Junior, a contractor—as is Red, and one of his sons—built the house for a customer’s family, but later connived to get it for himself and his wife Linnie. The couple raised Red and their daughter Merrick there. Not long after Red married, his parents were killed at a railroad crossing. He and his wife Abby inherited the house and brought up their own family there–four children, or three, depending on who’s counting (ah, but that’s another story…there are so many stories here, so many branches on the family tree).

The second “defining” Whitshank story also concerns scheming to get what belongs to someone else: Red’s sister Merrick fell in love with her best friend’s fiancé, lured him away, and married him (and Abby fell in love with Red just days before that wedding, at the house on Bouton Road, on a “beautiful, breezy, yellow and green afternoon”–but that, too, is another story…).

Thus Tyler deftly hooks us, reels us in, and begins uncovering the back-story, the back-stories, of the Whitshank family. And everyone is an unreliable narrator. Since Abby’s memory is failing, the Whitshank’s adopted (well, not quite) son Stem and his family move in to help, and elusive black sheep son Denny comes home. As Denny vies with Stem to be helpful, trouble ensues and Tyler unspools secrets and mysteries. Gradually, the reader becomes almost omniscient, piecing together more of the Whitshank history than evident to any family member–past or present. Hints, clues, motives, and evidence, are sprinkled across the pages and throughout the house Junior built with perfectionistic attention to detail. Each room, as well as the contents of built in cabinets and drawers, matter here–like in a classic mystery, or the board game “Clue.” (Remember? Miss Scarlet did it, in the Library with the…) Yes, I can almost imagine the Whitshank family playing “Clue,” on their deep shady porch on a humid afternoon, competing for seats on the porch swing.

Oh! That porch swing! Keep an eye on it! And be on the look-out for a spool of blue thread in Abby’s sewing supplies in the guest bedroom. And be prepared—particularly if you are a reader who is also a writer—to finish the book and then start reading again, intrigued by how it is that Tyler accomplishes her magic tricks with the ingredients of, shall we say, slightly heightened, every day experience. And not quite ready to be turned out of heaven.