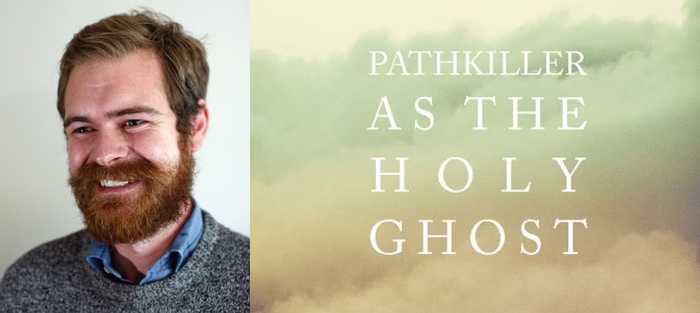

Now and then, some trick of fate, heredity, or self-awareness gives a person early confidence in their own skin. That is, they seem fully formed, skilled beyond their years. Tradesmen often have this characteristic; when I first met him, Nathan Poole had been providing for himself and his family for years as a carpenter, plumber, and workman in the building trades. He’s one of those quiet, thoughtful men who listens to the world of nature and spirits, the place where the bears live—which was the nature of that first conversation—a bear—more specifically, bear scat.

It was a claustrophobic July at the deeply wooded Warren Wilson campus, where Nathan and I were both candidates in the MFA Program. I had seen a little pile of organically processed blueberries artfully deposited on a narrow footbridge. It’s the sort of thing you want to tell people about, talk over, consider—a black bear’s occupancy among our gathering of writers. However, in a low-residency MFA student body filled with Brooklynites, San Franciscans, and other urban personalities, no one seemed interested in the territorial significance of bear poo, as I quickly learned to call it, until I bumped into Nathan. He radiated a kind of rural competence, and indeed, he was perfectly equipped to carry a conversation about the nature and meaning of such sign.

Today, Nathan’s trade is the construction of literature, as it ought to be. His stories have appeared widely, and he gained particular notoriety for work that regularly appeared in Narrative, including his story “Stretch Out Your Hand,” which won their fall 2011 Story Contest and received the Narrative Prize in 2012. In addition to Father Brother Keeper, published earlier this year by Sarabande Books, Pathkiller as the Holy Ghost was awarded the 2014 Quarterly West novella prize and has just been released. He was the 2013-2014 Milton Postgraduate Fellow, sponsored by Image, and in conjunction with Seattle Pacific University. This year, he is teaching fiction as the 2014-15 Beebe Fellow at Warren Wilson College, where he earned his MFA, and where he met our bear that long-ago July.

It was, in fact, a black bear, an old boar that had been gorging on the blueberries near the dorms. They encountered each other face-to-face at a little bridge where Nathan had decided to walk his dog.

Did I mention that Nathan exudes a kind of spiritual awareness, that myth and deity seem present in his work? The stories in Father Brother Keeper grip the reader in a world of tactile, immediate experience, a world of strife and often, innocents in pain. You could feel afflicted, but the stories are told with such great understanding of this natural stage and with such an abiding affection for those of us caught in its trouble, they leave the reader feeling gifted with a sense of grace. When Nathan and I returned to our conversation about signs six years after our first meeting, I felt compelled to focus on the elements of nature and theodicy in his work.

And the bear? Nathan says he was in the middle of the bridge, and that both of them took off in opposite directions. But I’m not sure I buy that. He would have had to keep his dog from chasing down the larger woodsman. I think Nathan went on across that bridge and into the forest he talks about below.

Interview:

Rolf Yngve: Nathan, congratulations on all your successes, and even more, congratulations for this wonderful collection, Father Brother Keeper. We’ll talk about the stories, but something came up in the author’s notes that I thought might kick us off—you call yourself an amateur dendrologist and theologian. Tell me about that. Or, what I want to ask really, where would you rather start, with the dendrologist’s interest in hardwoods or as the student of Job? I feel like I should have the King James Bible and The Field Guide to North American Trees and Shrubs next to me when I read your stories.

Nathan Poole: Ha! Well, I guess they could both be considered field guides, in their own way. I can’t choose which to start with. This is so funny. I walk around all day fantasying about being asked this exact question and when someone actually asks me, I feel totally speechless, like Charlie Brown trying to spell beagle.

Not to evade the question, but in a really basic way the words “God” and “Tree,” at different times in my life, became suddenly insufficient. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to see those things as two of my antecedents. I became desperate for a more meaningful encounter with both of them, which for me typically means new language. I wanted to press into those categories to expose their uncanny qualities, their musical qualities—say, black chokecherry or honey locust, stand up on the knees of a bald cypress, lean into the buttress of a water tupelo (Nyssa Aquatica). It’s all a seduction. “Who touches the mountains and they smoke?” [a paraphrase of lines from Psalm 104.] “What did you go into the wilderness to see, a reed shaken by the wind?” That’s from the Gospel of Matthew. It’s crazy and beautiful. Why hasn’t that been put on a billboard?

I think I realized at some point that I would never understand my native place, my family, my home, without becoming something of a theologian. I think there can be both valid reasons to flee the world of faith and equally valid reasons to press into it: if I was going to discover a little more about who I was in the context of my native religion—which in the South is not just Christianity but also a strange, dangerous amalgam (or, to be critical, conflation) of politics, social and historical strands, economics, and family—I had to start getting honest with myself about those things in my tradition that have never worked for me. I started a list of things I thought I could still believe in. It was very small list at first. I found others who had also spent their lives making a little list of their own: Karl Barth, Bishop Wright, Thomas Merton, Simone Weil. Oh, there’s so many others, but you get the idea.

What about this study of hardwoods, though?

What an amazing start to a paragraph that someone more knowledgeable should be finishing. You know, my pastor was a forestry major when he got “the call.” There has to be something to it.

I’m not sure why or how I got into studying and identifying trees, and most days I really can’t call it “studying.” I just happened to live up against a national forest, and my dog needs long walks. I guess one thing lead to another. I do believe, though, after having that interest for a few years, that all North Americans have the forest in their blood and therefore have either a strong attraction or aversion to it. The forest can be a place of peace, or a place of hauntings. Like working land, it has dynamistic power, or “strength” as James Dickey might say.

The mythic, or mystic sense of the woodland—it seems so much a part of your work.

I’m not being mystical as much as I’m being practical. These are the places that sustain us, that generate the air we breathe, what we eat, that’s what I mean by dynamism. Of course this has all been said before, and recently. But why shouldn’t fiction remind us of that relationship? We may no longer belong in a forest, but we still belong to it. Someone healed suddenly of his blindness once said, “I see people, but they look like trees, walking.” Why would anyone say that if those images were not in their blood, as a likeness of the self? Anse, in As I Lay Dying, talking about his family, said, “When He aims for something to stay put, He makes it up and down ways.”

I’m not being mystical as much as I’m being practical. These are the places that sustain us, that generate the air we breathe, what we eat, that’s what I mean by dynamism. Of course this has all been said before, and recently. But why shouldn’t fiction remind us of that relationship? We may no longer belong in a forest, but we still belong to it. Someone healed suddenly of his blindness once said, “I see people, but they look like trees, walking.” Why would anyone say that if those images were not in their blood, as a likeness of the self? Anse, in As I Lay Dying, talking about his family, said, “When He aims for something to stay put, He makes it up and down ways.”

I think the stories in this collection, especially “Anchor Tree Passing” and “Year of the Champion Trees,” are an exploration of the crazy, idolatrous relationship I have with trees as a likeness of something both divine and human, and maybe I’m asking the question, “Does anyone else feel this?” All right, where are we? Help me.

Well—okay—then let’s go back to God for a moment. I suppose owing to the enormous suffering of the world at this moment in our history, I’ve been thinking a lot about the divine and the human. Perhaps it was only a reflection of this preoccupation, but as I studied the stories in Father Brother Keeper, I could not help but consider the question of Job—in my mind, the question of evil and the suffering of the innocent. Then, when I read the review copy of your novella, Pathkiller as the Holy Ghost, I was delighted to see that it was an extension of your story “The Firelighter,” and even more provoked to find my sense of this deep thematic river in your work confirmed by your quote of Job’s famous cry: “Am I the Sea…?” (Job: 7:12-14). Of other stories, I think Job is clearly knitted into “Stretch Out Your Hand.” And “Fallow Dog” is a study of bewilderment over evil, and a study of its pervasiveness. Tell me about your thoughts regarding the questions of evil and innocence in these stories.

Oh, my. Job is deep water, deep poetry. I’m just as qualified to talk about Pound’s Cantos as I am to hold forth on Job. At least Pound is in English.

I know we could talk on end about theodicy and evil, and all that business, but I have just never felt that’s what Job is about. I’m with Max Weber on that score, at least in the sense that I think the question of theodicy is an irrelevant question, related to society and not arising from the individual who seems to understand suffering as something intrinsic to life. I’ll just say something crazy and leave it alone, which is: God asserts divine power by succumbing to the mystery of suffering, not by conquering it, and that’s the story of Job.

I’m led to believe that God lays down with us in our sick beds, swims our salted anxious seas, and dies alongside us every literal and figurative night, all in order to wake with us. In the gospel account of Matthew, Christ says something remarkable: “Are not two sparrows sold for a penny, and yet not one of them can fall to the ground apart from God.” That’s a wonderful translation because of that simple preposition, “apart.” The Greek isn’t difficult here, but the English can be taken two ways. If you read the word “apart” as meaning “outside of consent” you’re quickly dead-ended by the question of suffering and innocence. If you read the word as I think it wants to be read, as “without” then you are left in a place infinitely more mysterious and graceful, which is that God is with and within all the innocents who suffer. That’s all I’ll say about theodicy.

But in a broadest sense, I have to say that the aesthetic idea of pathos is not going anywhere anytime soon for artists, and Job is a piece of art. Writers like Breece DJ Pancake, Lydia Peele, and Peter Orner exert a huge influence on these stories, and I’m drawn back to their work, again and again, because of the deep feeling, the pathos in their art. It’s amazing to me, then, that I don’t need to do anything other than try to write a good story to have something profound in common with Job, but I don’t think this book utilizes Job in any specific way. The novella totally does, but not this book.

Just the same, the Eliot quote that serves as your epigraph seems aimed at the notion of suffering doled out by God. It’s from Stanza IV of “3 Preludes” in Prufrock and Other Observations:

I am moved by fancies that are curled

Around these images, and cling:

The notion of some infinitely gentle

Infinitely suffering thing.

I first encountered that quote in Harold Bloom’s The Art of Reading Poetry. His reading of “Preludes” is totally in opposition to so many readings that suggest that Eliot is condemning modernity and humanity in that poem. Bloom’s reading is essentially incarnational. It goes like this: There is something curled around the images of our life, something graceful that is unseen, and yet it still moves us. As the “blackened street” is impatient to assume the day, God is impatient to assume the world in the form of something infinitely gentle, something misunderstood, and therefore something that suffers in a profound way. This is the story of Job only because it is first the story of humanity—and now I’m getting into some of Karl Barth’s territory and should give it a rest.

Okay, let’s look at another aspect of your work—you’ve worked as a contractor and a carpenter, so I suppose it should come as no surprise that you know something about construction. I’ve been always very impressed with your seemingly effortless handling of narrative structure. And the variety. Some stories seem eager to step out beyond their borders. They are, I think, complete and satisfying in themselves. But they also have the legs to make us imagine more. The stories “Silas” or “The Firelighter” come to mind; they seem so much part of a larger narrative. Others seem perfectly closed, the door shut and wrapped around the end. “Stretch Out Your Hand” does not seem to want even another word. I have to ask, how do you come to the stories’ structures? Do you work within the bound of a completely understood narrative? Or must you search for the story as you work on it?

I don’t understand anything going in, just that I’m ready to write and that I have a bit of language that I think is about to blow everyone’s mind (which I usually end up cutting). I try to allow the story to develop from one opportunity to the next, and I try not to insist on anything anymore, only those things that are suggested by the work itself.

Stacy D’Erasmo once told me in an MFA workshop that I was slamming doors in her face. I think it’s rare these days to have a faculty member fully speak their mind in a workshop, and if she hadn’t said that, I think I might still be screwing up every single story I tried to write by insisting on certain symbols, images, and actions, especially as they relate to the story’s ending. I went on to combine that comment with another comment she made on the work of a fellow student about dramatic scale in fiction and had myself an “ah hah” moment that has changed the way I think about endings for the last five years. I really do try to assess the scope or scale of a story’s dramatic movement and to consider whether the story is going to move toward a gesture for closure—and I try to let the closing gesture match the action of the story, in its loudness, or quietness, so as to not “slam the door”—or whether the story will move in the direction of what John Gardner has termed “Logical Exhaustion,” which I understand as bringing the story to a place where the character or world is sufficiently known, and we don’t need to continue on in the action of the story to have the story live on in us as readers. Logical exhaustion is a kind of handing off to the reader, as in: you get it; this is yours now. Several of the stories that you say “have legs” end that way.

I want to indulge in a little excursion, here, to dissect some of your prose. Whenever I’ve read your work, I find myself stopping at the line and paragraph level to consider the elegance of your word choice, construction and syntax. This is from “Lipochrome”:

The fence had been there for a hundred years and it lifted and sunk where the roots of the oak pressed up beneath it, causing sections of finials to aim upward in concave depressions and others to fan out lethally like the rays of the sun on old celestial maps.

That construction carries a lot of water. It first reaches to the past: “The fence had been there for a hundred years.” Then the fence’s power appears in a tremendous movement: “and it lifted and sunk.” But this is no ordinary movement; it has an ancient and subterranean pulse, “where the roots of the oak pressed up beneath it.” Moreover, the fence is causative, an actor in the story: “sections of finials … aim upward in concave depressions.” The adverb “lethally” then sharpens the sentence into a threatening foreshadow of the events to come and lends a sense of tension to the final simile, again reaching into the past: “like the rays of the sun on old celestial maps.” Of course, the fence plays a pivotal role in the story; something happens that would seem almost impossible if not for the power the language of that sentence gave that stationary, physical object.

I’m not sure how to parse all the means you used to write that way. But it seems to me that part of the weight of this language is in the use of words from a different place and time. For example, “finials.” Or, a horse is described tied to the fence by its “bosal.” The story’s title, “Lipochrome,” is not found in the lexicon of most readers. This sort of word choice seems to impart a kind of authority or verisimilitude to your writing, especially in this story and also, particularly, in “The Firelighter” and the novella. You seem to have a mind that covers one hundred and fifty years of technique in any number of crafts. Firelighter, for example, has all these details about steam locomotives. Where did you come by these words and this language?

Wow, thank you for that gorgeous reading. Isn’t close reading always better than anything else? It’s so exhilarating. As far as verisimilitude, I really don’t do as much research as I should. The details are just always there and I’m absolutely faking it. I actually have to restrain myself because I’m such a sucker for affectations. I’ll quickly romanticize historical settings and figures to the point of sentimentality. So it’s never a problem of generating the details—they are just there, I can’t explain that—it’s always a problem of trying to not make the past one big fetish.

I think some of the most compelling details in the “Firelighter” story came from my grandfather, who we’ve always been told is Cherokee and who worked for the railroad as a young man before they switched over to diesel engines. I tried to keep his voice in mind and to filter my affectations through his voice to keep things real.

Sometimes I hear Eli Cash from the movie Royal Tenenbaums—the scene when he is reading from his novel—coming through my own prose:

The crickets and the rust-beetles scuttled among the nettles of the sage thicket. “Vámonos, amigos,” he whispered, and threw the busted leather flintcraw over the loose weave of the saddlecock. And they rode on in the friscalating dusklight.

At that point, I say, all right, you’ve gone too far, this is getting silly, and I start trying to be a real person again.

I’d like to wrap this up where we began: you and I share an interest in Orison Books, Luke Hankins’ publishing venture out of Asheville. Luke’s vision is publishing work from “the life of the spirit, from a broad range of perspectives.” I think your characters have an abiding awareness of their spiritual life. The audience you’ve found is within the literary journals and academic writing competitions. You yourself are directly engaged with the academy as a teacher. Do you consider yourself a writer of faith, and if so, do you feel any impulse to edit the aspects of faith in your fiction in response to the audience you’ve found?

Faith is obviously a paradigmatic word. I think the scientists who built the Hadron collider in Geneva were people of faith, believing they would find something, some answer to the problem of locality in particle physics or whatever it’s called. They would probably disagree with the word “faith” and say they were working with specific empirical evidence, and that evidence is the opposite of faith. But I mean—come on—successfully describing and predicting the way something might act is not the same thing as explaining it, not by a long shot, and I don’t think it drives us in the same way. These scientists exposed the deep unseen magic, but they don’t intrude on its strangeness, and that’s my point. These faith-based quests have more to do with us and what we find beautiful and how we ratify our personal identities. They build and operate colliders to stun the world with its own intricacies, make the world worth living in. They don’t pretend to explain it. That’s faith. I write stories for those same reasons.

The question is really about the form faith takes. Mine takes a particularly religious form, and I don’t feel any need to edit my work because of my identity as a person of religious faith. This might be different if I were in a different field, but I write fiction and the real essence of faith, the crisis that is human faith, will always be hidden in experience, and that’s what fiction is, meaning hidden in experience. As Isaiah writes, “truly you are a God who hides yourself…”

The question is really about the form faith takes. Mine takes a particularly religious form, and I don’t feel any need to edit my work because of my identity as a person of religious faith. This might be different if I were in a different field, but I write fiction and the real essence of faith, the crisis that is human faith, will always be hidden in experience, and that’s what fiction is, meaning hidden in experience. As Isaiah writes, “truly you are a God who hides yourself…”

Religious faith will always be a crisis of praxis for me. It is both a theory of suffering and a way to suffer. Marx is famously quoted out of context as saying that religion was an opiate for the masses, a drug wishful people could take to make themselves feel better, feel safer, but anyone who has had a religious experience knows it’s the opposite. Marx himself, in the same statement, didn’t seem to intend that interpretation. He called religion the “heart of a heartless world” both referring to it as a life-giving thing and a contrivance at once. If you do that math, that equates to a logical crisis, to tremendous intellectual suffering. My faith asks me to know and suffer the paradoxes of the self and doubt unto joy, to pass through suffering with others and with God, not out of it. Writing is a way to do that, a form of suffering that leads to joy. Related is something Simone Weil once said: “Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.” This kind of consummate attention is what I feel called to as a fiction writer—it can be called empathy, of course, and it is that, but it also transcends that category. It is empathy and response, a kind of longing in language toward meaning.

Thanks, Nathan. It’s always such a pleasure to talk to you about your writing, or bears for that matter. I always go away feeling as though you’ve opened some new door for me. One last question: the Beebe Fellowship at Warren Wilson is a one-year post finishing up this summer; what are your plans for the future?”

My wife is applying to graduate schools right now to study speech pathology, and that’s our big dream at the moment. It’s likely that I’ll go back to contracting work of some kind to support us in this new phase, possibly agricultural irrigation unless some sort of teaching opportunity presents itself. I’m attracted to hard, honest work, and good lord, teaching keeps you honest, especially if you love your students, you work hard for them. I’m on a twelve-hour load here at Wilson, and I sleep good at night! But I guess the real answer is that we have no idea what’s next, not yet.