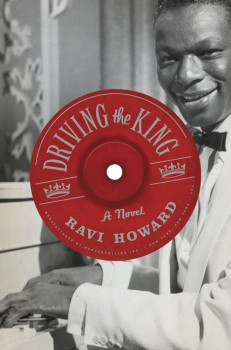

I met novelist Ravi Howard at last year’s Callaloo conference, held in Atlanta, then again at the Minneapolis AWP conference this spring, where Ravi kindly gave me a copy of his second novel, Driving the King.

Driving the King opens in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1945. Rising star and favorite son Nat King Cole returns for a rare hometown performance. Cole begins the show with a number helping an old friend propose to his gal, but is immediately attacked onstage by a half-dozen white men. Before they can do any serious damage to Cole, that old friend—returning soldier, Nathaniel Weary—leaps from the balcony to rescue him, pummeling one of Cole’s attackers. After the fracas, Weary gets ten years in prison, losing his girl and his sense of self. But he doesn’t lose his old friend: as Weary’s release nears, Cole sends an emissary to offer him a job as his driver and bodyguard out in Los Angeles, where Cole—by 1955, one of the world’s biggest-selling pop stars—is about to be the first African-American to host his own national television show.

There is much to admire about the book, but first and foremost I was intrigued with its narrator and main character, Nat Weary. I trusted him and quickly came to care about him and feel his emotional struggle—the weight that circumstances and the harsh realities of Jim Crow had placed on him—and so allowed him to open up slowly. And he did. It took Weary a while to confide some of the more personal, raw emotions. This felt realistic and psychologically true. I admired his moral crisis and the character he showed in facing it and working through it. His actions later in the book became wholly satisfying. I was also interested in the ways that Howard wove together history and fiction—in particular, the private world of Nat King Cole.

Ravi Howard won the 2008 Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence for his novel Like Trees, Walking. He was also a finalist for the Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award. Howard has received fellowships and awards from the National Endowment of the Arts, the Hurston/Wright Foundation, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and the New Jersey Council on the Arts. Howard’s work has appeared in Callaloo, the Massachusetts Review, the New York Times, and on NPR’s All Things Considered. As a sports producer with NFL Films, he won an Emmy in 2005 for his work on Inside the NFL. He lives in Atlanta, Georgia.

Interview:

Sebastian Matthews: The voice in Driving the King reminds me a lot of Mosley’s Easy Rawlins’, especially in Devil with the Blue Dress. I admire that novel in large part due to Easy’s wise, sad, street-smart, soulful consciousness. He’s such a perfect narrator—part gumshoe, part Everyman storyteller, part social commentator/philosopher. Nathaniel Weary is just such a narrator—and, of course, just such a character. Can you tell me how you came to write through his voice? Did you know you wanted to write about Nat King Cole first or did Nat Weary arrive and escort you to Cole?

Ravi Howard: The challenge was that Nat Weary was in conversation with Nat Cole. So the sideman becomes the lead and the leader is in some ways a supporting voice. I try to look at dialogue as the flow of an ensemble, considering how other members react to the one leading the conversation. So in a lot of ways Nat Cole is in a supporting role. I like the Mosley work because he heightens the story when Easy Rawlins reacts to dialogue or violence. He has to respond in the moment. Wayne Shorter had a quote about his musical style, saying he wanted his work to have mystery and velocity. I try to structure the fiction, both dialogue and action, to have those elements.

I always wanted to have more of the Everyman tell his story and a piece of Nat Cole’s. Growing up in Montgomery, I heard stories about the Civil Rights Movement from people who never became famous. That experience had an impact on my storytelling. I saw the texture and power in the experiences of people who were anonymous beyond their communities. Those folks are common in creative narratives, so those voices fit the style I wanted to develop.

It seems to me that, in memoir, the narrator should be a real walking and talking character—as in much first-person fiction—someone who enters into the story the narrator is telling. We follow him/her as we follow a guide or a good friend. Driving the King reads like a memoir—a fictionalized memoir?—maybe in part because of the historical figures who populate it. Can you say a little something about how his story—as opposed to the larger story of civil rights and bus boycotts—came into being?

I wanted Nat Weary—his family and his personal history—to be something of a prologue to what happened in 1955. So much of that boycott moment had been simmering for years. He was among that generations of black soldiers who had less freedom than the German POWs who came to the U.S. Also he was in Montgomery before it became famous. I think there are parallels to showing the early days of a future star. The before and aftermath hold lots of subtext. Nat Weary has to deal with all kinds of aftermaths. Even the sense of newness of Los Angeles became familiar to him. I wanted to create someone who was deeply aware of the old and the brand new.

Can you say more about this awareness of “old and the brand new”—why is this important to Nat, as a character, and you, as the author? Do you feel this is something fiction is particularly well suited to do: going into these “lesser known” parts of history?

When I chose to create a character who had been imprisoned for ten years, I wanted to see how time in his mind differed from the world around him. He had imagined a new world for ten years. Once he was free, he had to reconcile what he imagined and the new reality. He didn’t have the gradual passage of time that hides certain changes. The flip side is that he was well aware of what had not changed in terms of Jim Crow. The imagination is often more progressive, and that was especially true in Weary’s case. I used as an epigram an Albert Murray quote. He said, “Fiction is an art of make-believe.” We are in the heads of writers and characters who are both creating a reality.

The research in Driving the King is impressive. I like the blending of historical truth and fictional constructs, especially how Nat King Cole becomes, slowly, a full character. He starts more as a stalking horse for the larger story, which seems something solid for you to build your larger story around; but, by the end, I feel deeply his character and his connection to Weary. What were the biggest challenges writing about characters we already know/have read about?

The research in Driving the King is impressive. I like the blending of historical truth and fictional constructs, especially how Nat King Cole becomes, slowly, a full character. He starts more as a stalking horse for the larger story, which seems something solid for you to build your larger story around; but, by the end, I feel deeply his character and his connection to Weary. What were the biggest challenges writing about characters we already know/have read about?

As far as Nat’s singing voice goes, that was available from a wealth of sources, but I was just as interested in Nat Cole’s speaking voice. Beyond that, what was the private speaking voice that he used among those he trusted? I think the mark of a balladeer was that feeling of genuineness in the lyric. The storytelling in the voice has always been compelling to me. I was intrigued by how much of that monologue feeling of a ballad works in the dialogue. I like the idea of a conversation having the same feeling as a duet or jam session. Voices might work together, or they might compete.

One key was that I was playing in a personal space that doesn’t figure into biography or documentary because I imagine it based on research or feeling. The freedom of it has challenges, but ultimately it shows how we write and imagine history.

I love your analogy of a conversation as a duet or a jam session. Did you approach the composition of your scenes between Weary and Cole in this improvisatory manner? By this I mean, did you let the two old friends just start “jamming” and see where they ended up? Or did the scene itself dictate the flow of conversation?

In many places that was the key to it. I don’t play or read music, but I do marvel at the back-and-forth within an improvised piece. You can feel that the musicians are playing as much as they are listening. They speak to one another as much as they do the audience. I try to enter and leave the dialogue sections with a sense of what has changed or developed in the story, but it’s not a straight line. We circle to a sense of understanding. I think it speaks to your questions of old and new. These characters examine familiar terrain, but each pass brings a new level of understanding or tension.

I am interested in how the characters speak to each other so directly and so forthrightly about the matters at hand. Many of the recent novels I have read seem to have their characters talk indirectly about the thing they’re trying to understand or get across. At times, it seems the author knows more about intentionality in these novels than the characters do themselves. Your main characters seem to understand exactly what they are saying and why (and when it might have more than one meaning, depending on the situation). There is a purposefulness and intention that stands out in Driving the King. As a reader, I wondered if this has to do with, at least in some part, the political and social climate: that it required such discourse, or brought out this tone or style in more relief.

It’s fascinating that one of the major figures of the era, Andrew Young, became a U.N. Ambassador. I think black people during the Jim Crow Era had to perfect a form of diplomacy. Sometimes it came from teachers, lawyers, ministers, who had a public, vocal component to their training and work. They were orators. But I also think folks who were working as maids, porters, or other service jobs had a form of it as well. With the threat of violence around them, the skills to de-escalate were important. I think I like to show that in the dialogue. The black community of Montgomery had to negotiate peace on personal level for wages and safety. In many ways, there was solace in having a collective response to questions they had to answer individually for years with much less agency.

I like a Vievee Francis poem, “The Wheel on the Bus,” that shows the reaction of Rosa Parks when she sees the bus she rode before getting arrested. “Rosa kicks out the front window of the bus…She kicks in another window of the bus moving nowhere, moving through the streets of Montgomery. She eases into a front seat.” It vividly shows a reaction Parks could never have had in that moment, but the poet gives her the audience and private space where she honestly reacts. I like that confidential space where our characters can react in direct terms without the kind of diplomacy that the times sometimes demanded of them.

Can you talk a little about the narrative weave you create in this book—the shifts back and forth in time? You have Weary’s time in the war, the first concert when Cole is attacked (and Weary saves him), and the second concert that Weary and Cole put together to redeem and, in a sense, replace the first one…

I wanted to create space between chronology and structure. In looking at memoir—and this goes back to your question about fictional memoir—I’m fascinated with the way that life is recorded. Memory ends up trumping chronology. These personal arcs play out in ways that are move vivid that a timeline. I needed to get away from a timeline focus that dogged me early on in the writing.

Also, I thought about how singers go back to the same song night after night, but it changes. A song is both a historical marker and the way it changes over time with each performance. I think the fictional memory works in that same way. Weary looks back and wonders, What if. Returning to Montgomery gives him and everyone else a chance to see and hear that What if. I like to play with the way that imagination may eventually become reality. With that internal voice we hear in characters and narrators, we can experience that space and time between the idea and fruition.