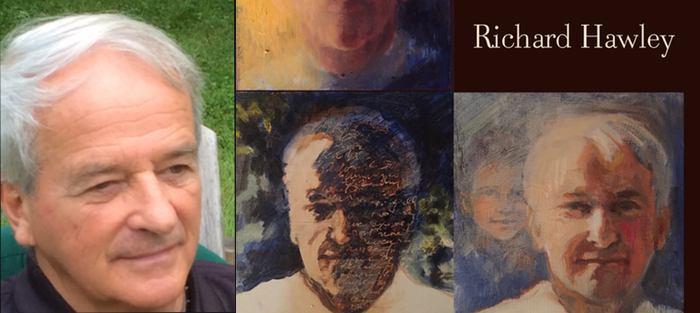

Richard Hawley’s novel The Three Lives of Jonathan Force (Fomite, 2016) is a potent but unhurried meditation on the entire life—from birth to death—of a famous cultural pundit named Jonathan Force. Aptly named, Force is best known to the world for his works of nonfiction, which have titles like Force Factor and Reasonable Force, but the novel, narrated by Jonathan Force himself, is far more interested in the development of Jonathan’s person than in his fame and influence.

As the title suggests, the novel unfolds in three distinct parts. The child Jonathan is full of wonder and conviction; as a middle-aged man, he is an expert, comfortable with success; and in old age he finds wonder once again, but this time the wonder is accompanied by freedom. Each stage of Jonathan Force’s life is rendered convincingly, but the “middle” stage—in which Jonathan describes his developed theories as well as their reception by the public—feels eerily real, a private and behind-the-scenes take on the life of a thinker whose work, though only partially understood, nonetheless influences the intellectual culture of his time.

Richard Hawley has spent much of his life as a teacher and headmaster, and has published a number of fictional and nonfictional works, in book form and in publications such as The New York Times, The Atlantic Monthly, and The New England Journal of Medicine. Much of his nonfiction has centered on understanding and helping boys in an educational setting. He is also the author of The Headmaster’s Papers, which was first published in 1983.

This interview occurred as a series of email exchanges during the month of August.

Interview:

Mindy Misener: This novel comprises three books that cover, in order, Jonathan Force’s childhood, middle adulthood, and old age. Tell me where you started—beginning, middle, or end—and how and at what pace the novel grew from there.

Richard Hawley: The novel was conceived from the outset as the story of a whole life, from first sense impression to last breath. Composing it in three separate books—as “three lives”—grew out of my conviction, as I advanced to the threshold of Old Age, that in profound ways the stages of our lives are not really continuous; we have in effect not a single life, but lives.

Richard Hawley: The novel was conceived from the outset as the story of a whole life, from first sense impression to last breath. Composing it in three separate books—as “three lives”—grew out of my conviction, as I advanced to the threshold of Old Age, that in profound ways the stages of our lives are not really continuous; we have in effect not a single life, but lives.

This conviction took hold in me as, in midlife, I began reading a number of Jungian writers. One of them, Robert A. Johnson, wrote a wonderful little reflection on what he considers the archetypal stages of a man’s life. The book is called Transformation (1993), and in it he proposes that a fully realized man’s life unfolds in three trimesters.

In youth boys become aware of their spiritual connectedness to everything about them. Their enthusiasm and dreaminess can be energizing and infectious to others, but many of their most urgent urges and ideals are based more in illusion than reality. In this regard spirited boys are like the eponymous Parsifal (the name means “little fool”) or like Don Quixote who lovably tilts at windmills. This condition—at its best and at its worst—is youth. The youthful condition cannot manage the transition to mature adulthood in a practical, working world.

To make this transition youth must, literally, become disillusioned. He must learn to discern how the world really works, true from false, reality from fantasy. If he does, he will became shrewd and effective, very likely making himself materially and otherwise successful. But in the course of seeing through past illusions, he becomes dispirited and jaded. He may be wise, but he is not happy. He becomes in effect Hamlet, the smartest person in the play, but wondering if it might be better not to be.

But there is a path forward out of this condition. If, with courage and grace, the Hamlet figure is able to put aside his former certainties, he may be visited by urges—including wild, formerly suppressed urges—that carry him into dizzying uncertainty. A man willing to make this journey may finally realize himself—like Goethe’s Faust. But like Faust, who made a pact with the Devil, he may have to make peace with his very antithesis.

The notion of the trajectory of a man’s life as a kind of three-stage rocket rang true for me, and I was thereafter driven to embody such a life in the contemporary world. Thus, Jonathan Force.

I’m reminded of Stanley Kunitz’s poem “The Layers”: “I have walked through many lives / some of them my own…” How do you see the three-stage model as fitting (or not) with Kunitz’s uncounted “lives”?

The “three-stage” scheme proposed by Johnson is a basic, more sharply delineated structure. I believe it is archetypal for men committed to realizing themselves. As boys we cannot help being at times inspired fools. In our middle years it is hard not to grow disillusioned with the follies and imperfections of practical life. And as I suggested earlier, the way out of this knowing disillusionment is to risk opening oneself up to everything suppressed along the pathway to our “adult” selves. This passage from Quixote to Hamlet to Faust may include immersions in what may feel like even more lives—what Philip Roth calls “counter-lives,” what-if lives. Nonetheless, I still find the larger, three-stage structure compelling.

The Three Lives of Jonathan Force opens with a memory from when Force was about one year old and ends close to his death. What was it like to carve out the story of a whole life? What particular challenges did your task provide, and/or what particular gifts?

Narrating a life from infancy through old age was indeed a challenge, but it was also an adventure. The crucial element of the book, one without which the enterprise was doomed, is the authenticity of the voice narrating each life stage. The voice had to be true to Jonathan’s psychic range in each of his successive times of life, but it also had to be a voice a reader could at any moment credit as the voice of the character in preceding and subsequent episodes. Finding that voice, especially in Jonathan’s infancy and early boyhood, required a combination of focused recollection and meditation. The book is a novel, not a veiled autobiography, but I did work hard to immerse myself in certain vivid early childhood experiences, to the point that I felt I could reenter them. Once I was able to do this, the process was no more than faithfully recording what I saw, going where I went, wearing what I wore.

At the far other end of the sequence, as Jonathan falls mortally ill and dies, I obviously could not rely on regression and memory. Readers must judge, but for me narrating the experience of passing out of life came readily and with a specificity of detail that surprised me even as I inscribed it.

As a young boy, Jonathan Force is enamored of “the other world,” which seems best defined by his description of an attic: that which provides a “wonderful sense of a house beyond what anyone living in the house is thinking about.” One of the things I value in your novel is the dignity and wisdom it gives to a child’s perspective. Rather than use a few childhood events as background or back-story for later events, the novel presents childhood as a first and essential stage of life, whose events, and the thoughts those events engender, are no less important than the events that happen at the height of a career. How do you see childhood presented (or used) in other works of literary fiction? Do you see yourself reacting against that trend, or moving with it? How so?

You are very kind to note a “dignity and wisdom” in young Jonathan’s perspective. It is that, along with boys’ unguarded reverence for the beauty and tug of the given world, that make their coming of age stories essential to literature. The enduring stories in that form—The Sorrows of Young Werther, Great Expectations, Huckleberry Finn, The Catcher in the Rye—carry a deep recognition and appreciation of youth and youth lost. I don’t think anything like a “trend” could diminish the power of the archetypal story. It is always the Puer Aeternus [Latin for “eternal boy”]. It is always Icarus. It is always David meeting Goliath, the twelve-year-old Christ in the Temple discoursing with the wise. In our historical moment, if there is a “trend” in boys’ stories it is probably a desperate over-reliance on jadedness and despair, a tendency to equate authenticity with seaminess. And then of course there is Harry Potter, a trend unto himself. I personally like Harry’s resilience and pluck, but for me there are rather too many adventures.

As Jonathan Force meditates on his own television interviews, he tells us:

Television programs, especially news and interviews, are so indelibly formatted in viewers’ minds, that it is nearly impossible for them to think critically about the format and how it is shaping and limiting what they are hearing and seeing. Instead they think with the format, and for that reason television has the powerfully denaturing effect of reducing novelty, complexity, trouble, conflict and even wonder to the narrowly confined mental territory allowed by format.

Half of me cheers over this assertion because I agree that television teaches us more or less what to expect and then more or less delivers on that expectation. The other half of me wonders if all formats are so limiting. How do you think about the freedoms and limitations inherent in the format of a novel, in comparison to television and/or any other medium we encounter regularly?

This is a wonderful question—and a hard one. Yes, not only do formats, including the format of the novel, constrict and pre-shape our expectations of what they deliver, but, as Nietzsche terrifyingly noted, language itself constricts and pre-shapes reality in ways that keep Reality at bay. The medium may not be the whole message, but it is certainly a determining factor in what and how much we receive.

But as for novels, the so-called form has by now evolved so capriciously and so variously that, with the exception of strict genre fiction, a novel can do and be almost anything: an epic poem, a stream of consciousness, unreliable narration of impossible occurrences. For my part, I have always believed the novels I have written were novels because they shared certain features of other books known as novels. But I must also confess that my second published novel, which was written as a succession of journal entries by a dying woman, was rejected by the first editor it was sent to with the observation, “Is this even a novel?”

Who is to say? But for the moment novels may be the least constricting form of narrative expression.

That’s a funny response you got from the editor, given the meaning of the word novel. I would prefer that the novel continue to evolve—not to seek what’s new for the sake of being new, but to find new expressions and ways to tell the truth because that seems essential to human activity. What more contemporary novels do you think are truly novel? What’s valuable to you about them?

I would have a hard time reckoning a work as “truly novel.” I take terrific pleasure, however, in novels I find “very different.” There is nothing like the feeling of exploring new fictional territory, although when I step back to consider what is creating that pleasure, it is invariably the old archetypal structures at work in unexpected settings in unexpected ways. I was carried away in this manner by both Mark Helprin’s Winter’s Tale and Robertson Davies’ trilogies, especially The Deptford Trilogy, works which seamlessly juxtapose extreme naturalism and supernaturalism.

A central moment in the novel is based on a revelation Force has—or begins to have—while he’s waiting for a television interview to begin. How did that revelation make itself known to you? Did you bring the revelation into the novel, or did the novel reveal the revelation to you?

A central moment in the novel is based on a revelation Force has—or begins to have—while he’s waiting for a television interview to begin. How did that revelation make itself known to you? Did you bring the revelation into the novel, or did the novel reveal the revelation to you?

As I mentioned earlier, this novel accepts the assumption that a man’s life, if he is to realize himself fully, unfolds in stages and that the stages are discontinuous—breaks—with the prior stages. When Jonathan’s revelation begins to carry him off at the beginning of Book Two, he is at the peak of his career as a famous cultural pundit, a predictor of cultural developments. Then in an instant a kind of psychic message arrives, a sudden awareness of the deadening insufficiency of all of his achievements and attainments. Not to spoil plot, but Jonathan in the course of a very long night realizes not just the meaninglessness of “knowing it all,” but that his hard won and by no means ignoble persona to date has been an imposture. To re-find himself, all must change and does. But it would take a revelation.

The revelation is both shattering and, in some ways, part of the ordinary world. “It occurred to me that all I could really do was to continue,” Jonathan tells us, about the moments the revelation descends. And then later he says, “It is strange how that is possible—to form a kind of mental barricade between present business and urgent soulful messages.” I like this—the acknowledgement that revelation has its requirements; the acknowledgement that we seem to have little control over when it arrives or what it tells us when it does.

There seem to be a lot of opinions floating around about the role of revelation in fiction. Generally speaking, is revelation something you read for? Is there a kind of revelation (in fiction) that you prefer?

I would not say I consciously set out to read for revelations. I think of revelation in the biblical sense, as profound internal messages—always unexpected—announcing something world-changing, life-changing. Historically and personally, revelations occur. Long stretches of one’s life can pass without a revelation, perhaps even whole lives. But they do occur, and they are consequential. I have written novels in which characters do not have revelations, although I hope they have insights. In this one, it is essential to Jonathan Force’s realization that he be humbled and changed by a revelation.

Force admits that one of the most beautiful things about his childhood was the ability “to play [a] game with the children I loved without any need to declare it.” I love this. Naming the thing that we’re doing tends to take something essential away from that very activity. For example—I enjoy talking about, and writing about, books and literature. At the same time, some part of me hesitates over doing so, because picking apart the exchange between author and reader—between a story and a receiving consciousness—seems to threaten something intimate and simple about that exchange.

I think every serious writer agonizes over the match of language to the experience it is attempting to transcribe. The Nietzschean problem we talked about above is inescapable. One of my favorite poets, the late Robert Francis, wrote an exquisite poem about this problem, “Glass.” Francis wrote that the words of a poem should be glass, so “simple-subtle” that if you lifted the glass/words away from what they conveyed, there it would be—just as it is.

I believe that is what writers strive to do: to hold experience “just as it is.” The achievement is impossible, but hairs raise on the back of the neck when gifted writers come close.