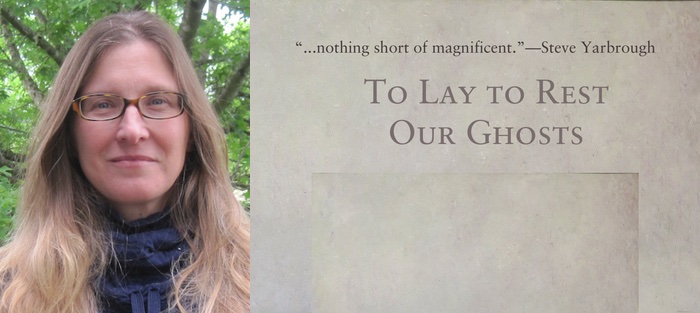

Caitlin Hamilton Summie is nationally known as a book publicist. She has spent the last twenty-plus years successfully shepherding new writers, especially new novelists, through publication and into writing careers. I’ve known her for almost as long, and while I knew she’d earned an MFA, I didn’t know her passion for writing—or that she was publishing, which came as a surprise. So did her stories, which are beautifully crafted and poignant tales of geography and place—and about where loss and family bonds fit in those landscapes.

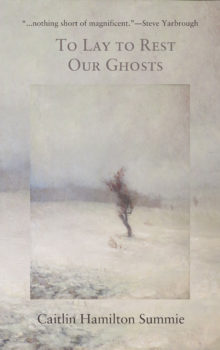

We chatted via email about her first book, a collection of short stories called To Lay to Rest Our Ghosts (Fomite Press); her literary influences; and how she finds the time for her own creative work.

Interview:

Steve Yarbrough: I’ve known you now for a pretty good while, nearly twenty years. I knew you’d earned an MFA, but I truly had no idea you were writing and publishing fiction until I received the advance copy of your collection. I see that several of these superb stories appeared in literary journals, but I can’t tell when they were originally published. So if I may ask, when did you complete the earliest story, and when did you complete the latest one?

Caitlin Hamilton Summie: I’ve always written, but it’s not something I discuss. As a book publicist, my focus is on other people’s writing, not my own.

The stories in the collection that were completed first were “Fish Eyes in Moonlight” and “Sons,” in 1992. Three stories were published in 1995 and 1996. They are “Tags,” which was the first story I had accepted, then I believe “Fish Eyes in Moonlight” was accepted and shortly thereafter “Points of Exchange.” I made minor edits to the stories for the collection.

The most recent story, begun in 2009 at my kitchen table in Colorado, was “Taking Root.” I completed it in Tennessee in 2015. I work full time running my own company and have a family so I write when I can, and it can take me a while to finish something. Often I get a really good draft done and then spend years polishing it. “Taking Root” was recently accepted for publication by Belmont Story Review. I think all my stories take a while, except for “Sons.” That story was a gift. I wrote it in twenty-four hours. I had nothing for my MFA workshop and something due the next day. Nothing like fear to motivate!

I didn’t try to publish much after about 2001. Maybe a stab here or there. I was so busy. I started sending stories back out in summer 2015.

What you say about beginning a story in 2009 and completing it in 2015 interests me for a couple of reasons: the first is that only once in my life, as far as I can recall, was I able to complete a short story after taking a break from it, and that break was all of ten days. The second is that if I had taken six years away from a story, I would be a different person when I went back to it. Yet the story you mention feels very much like the product of a singular perspective—and the collection, as a whole feels, feels like it comes from a fully formed artistic vision. So what went into creating that vision? And how has it remained so solid all this time?

What you say about beginning a story in 2009 and completing it in 2015 interests me for a couple of reasons: the first is that only once in my life, as far as I can recall, was I able to complete a short story after taking a break from it, and that break was all of ten days. The second is that if I had taken six years away from a story, I would be a different person when I went back to it. Yet the story you mention feels very much like the product of a singular perspective—and the collection, as a whole feels, feels like it comes from a fully formed artistic vision. So what went into creating that vision? And how has it remained so solid all this time?

Let me clarify that “Taking Root” wasn’t in a drawer for six years. I know for a fact that I worked on it in 2010. But it was indeed set aside for significant amounts of time. I pulled it out again in 2015 and did a few things to it and sent it out, but perhaps I tinkered with it other times.

I have changed over the years, but what surprised me when I put the collection together and looked at it closely is that my central themes and concerns have always been the same. Here’s an example: I pulled my title from one story. It was only when writing my reading guide that I realized that several stories reference ghosts, putting them to rest, carrying them on. I hadn’t remembered that or seen it until I had to come up with the guide.

Also, several stories in the collection link and are part of a novel-in-stories that I am completing, so there is a connection there that adds cohesiveness. Three stories link and are in the novel. Separately, two other stories link but are not in the novel. In the collection, I did not put them in order. I let them stand as stories, which they are and which was important to me.

The word “novel” has now reared its head, as it tends to. Do you find that writing a novel feels somehow qualitatively different? I do, so that’s why I am curious.

I have written longer works—novellas and novels. But I guess I’m not sure if writing novels is harder for me than writing stories, perhaps because my stories tend to be long and sometimes connect, perhaps because it takes me a while to write anything.

Let’s talk for a moment about the writers who have influenced you. I’m a Southerner, so people always expect me to cite Faulkner, O’Connor, and Welty. They’re surprised when I say that as much as I love those authors, the ones who meant the most to me as a young writer were Richard Yates, John Cheever, Graham Greene, Alice Munro, and William Trevor. Which writers exerted the greatest influences on you?

I came late to loving books, in some ways. I always enjoyed books, but I wasn’t always ravenous for them, as I am now. I was always ravenous about writing. My major in college was Middle Eastern history, my minor was philosophy, and so I have lots of reading gaps. But I can tell you that one of the books that struck me, changed the way I looked at worlds and writing, was James Salter’s Light Years. Other writers who have influenced me include Louise Erdrich, Ernest Hemingway, Frederick Busch, William Manchester, Milan Kundera, Barbara Pym, Richard Adams, Edward P. Jones, Jane Austen, Jhumpa Lahiri, and Penelope Lively, among others.

That’s a great list. For me a transformative moment came in the summer of 1980, when I pulled a copy of Salter’s novel Solo Faces off a library shelf in Jackson, Mississippi, and fell under his spell. When I talk to other fiction writers over the age of about forty, they invariably list him as an influence. My graduate students typically know nothing about him, but if I can get them to read him, they are usually mesmerized. Why does he exercise such power over the imaginations of other fiction writers?

I don’t know what it is about Salter’s work that mesmerizes, and now I realize that my copy of Light Years is missing, which is upsetting . . . I’d like to look through it again. But I remember being transported reading that novel, that the book led me to contemplate my own life without ever—somehow—taking me out of the story. For me, the best fiction and poetry reaches root deep, core deep. I remember the books that do that, or the authors who use language in revelatory ways. Or both.

If your new collection gets the acclaim it deserves, I suspect you’re going to find yourself wanting to devote more time to your own writing. Given the fact that you have a family and a successful business, have you thought about how you might make that happen?

First, thank you for that kind support. It means a great deal to me.

I imagine that I might want more time to write, but I also imagine that I will have to do what I’ve always done: carve out the time on a lunch hour, or after work, or on a weekend. I don’t see things getting any quieter in my house or business, as we are always off to a sports field or an ice rink, and the business continues to grow. In the last five to six years, I’ve managed to finish a middle grade novel (which I keep rewriting), and a story, and put together this collection. I’ve written some other things as well. I think that is pretty good output. Also, I wonder if I had more time, if I’d actually use it. The days when I have time to sit, which are rare, I never seem to sit. I always find something needs to be done. So if I had more time to write, who knows? I am going to count my blessings, I think, and go for it when I can.