Editor’s Note: As we approach our tenth year of publishing Fiction Writers Review, we’ve decided to curate a series of “From the Archives” posts that we’ll re-publish each week or so during 2017. Some of these features are editor favorites, some tie in with a new book out from an author whose work we’ve covered in the past, and some are first conversations with debut authors who are now household names.

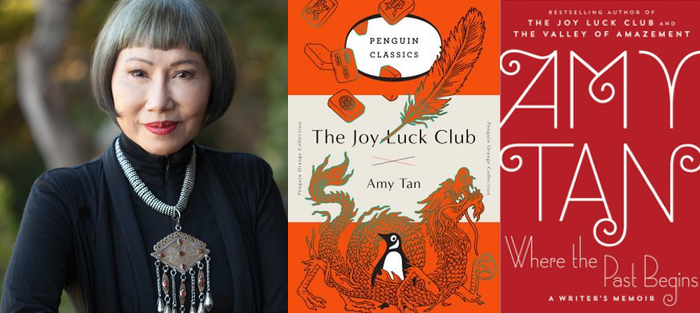

This week we’ve returned to J.T. Bushnell’s essay on Amy Tan’s story “Rules of the Game,” which was originally published on May 20 of 2013. Tan’s newest book, Where the Past Begins: A Writer’s Memoir, was released by Ecco last week.

I’m a white male. I feel guilty but helpless about how those facts might influence my reading preferences, especially since I’ve been charged with introducing college students to literature. I’m always on the lookout for authors I can love and teach who are not white, not male, and this is how I came to Amy Tan, who is, of course, neither.

“Rules of the Game,” from Tan’s debut book of connected stories, The Joy Luck Club, is widely anthologized, often by editors who share my demographic shame—white males, in other words, who are sensitive about promoting authors other than white males. Because of this, and because Tan’s later novels have veered toward the glossy covers and sensational titles of commercial fiction, I sometimes worry that other teachers, not to mention students, might dismiss “Rules of the Game” as a mere nod toward political correctness. But to do so would be to overlook a quintessentially American story, one that has roots in a literary tradition that dates back to Flaubert and Chekhov—a shame indeed.

The story is about Waverly Jong, the daughter of Chinese immigrants, as she ascends to the highest levels of competitive chess by age nine. It has a number of superficial pleasures, and this was what drew me in initially. I was delighted by Tan’s hilarious, acerbic portraits of the Chinese mother, full of pride and confusion and dislocated old-world values, speaking in her brusque broken English. As she tugs knots from Waverly’s hair, for example, Waverly teases her ruthlessness by asking about Chinese torture. The mother doesn’t understand it’s a joke, of course, and responds:

Chinese people do many things. Chinese people do business, do medicine, do painting. Not lazy like American people. We do torture. Best torture.

Tan also sends us running with adventurous children through the alleys of San Francisco’s Chinatown, and her descriptions of the place are sharp and entertaining. She shows a fish market’s display tank, for example, “crowded with doomed fish and turtles struggling to gain footing on the slimy green-tiled sides,” then goes further to show the hand-written sign instructing tourists, “Within this store, is all for food, not for pet.” These are details that show us both the physical and the psychic features of this world— not only its material substance but also its population’s attitudes, as well as the wider cultural attitudes impinging upon it. White visitors want to adopt the turtles; Chinese residents want to eat them.

This is how the details begin to signal the story’s larger themes of cultural conflict. The turtles show a basic incompatibility between Chinese and American values, and it shows the Chinese community’s readiness to defend their culture. This dynamic is carried to the extreme in the passage about torture. What cultural innovation could be more appalling than torture? It is an ugliness, which means excellence only makes it uglier. It should evoke anything but pride, and that’s why the mother’s prideful response is so funny. It shows how radically loyal she is to her Chinese heritage and how quick she is to criticize Americans, no matter what the topic. She prefers Chinese culture over American culture, and that preference outweighs nearly every other consideration.

Tan never mentions the cultural implications of these things. She doesn’t even let her characters fully recognize them. In fact, she never once uses the word “culture.” Instead, she embeds these ideas in the details—description, action, characterization—a narrative technique originally developed by realists such as Flaubert, whose goal was to be “present everywhere and visible nowhere” in his stories. He believed, in other words, that the author should align every narrative element with a story’s deepest themes (“present everywhere”) but never intrude on the narrative with overt announcements or simplistic allegories about those themes (“visible nowhere”), as many writers before him did. The effect, as Travis Holland describes it in his FWR essay “Present Everywhere, Visible Nowhere: Flaubert’s Eye for Detail,” is that such details can “paint a vivid scene, often beautifully, but look a little closer and you’ll discover that the solid ground you’re standing on is in fact ice. And under the ice, in the dim green light, another story is being told.”

The ice, in this case, is Waverly’s pursuit of chess, while the cultural conflicts swim in the dim green light. Waverly, born American to Chinese parents, is growing up in two worlds. Tan even gives her two names, one that ties her identity to each culture. Her official name, “Waverly Place Jong,” comes from the street her family lives on—quite literally a patch of America, albeit a long and narrow one. Her family calls her Meimei, Chinese for “little sister.” Not surprisingly, she has learned to maneuver through the incompatibilities of these two worlds. One such incompatibility arises when Santa asks her age. Waverly narrates, “I thought it was a trick question; I was seven according to the American formula and eight by the Chinese calendar.” She has a solution, of course: “I said I was born on March 17, 1951. That seemed to satisfy him.”

The ice, in this case, is Waverly’s pursuit of chess, while the cultural conflicts swim in the dim green light. Waverly, born American to Chinese parents, is growing up in two worlds. Tan even gives her two names, one that ties her identity to each culture. Her official name, “Waverly Place Jong,” comes from the street her family lives on—quite literally a patch of America, albeit a long and narrow one. Her family calls her Meimei, Chinese for “little sister.” Not surprisingly, she has learned to maneuver through the incompatibilities of these two worlds. One such incompatibility arises when Santa asks her age. Waverly narrates, “I thought it was a trick question; I was seven according to the American formula and eight by the Chinese calendar.” She has a solution, of course: “I said I was born on March 17, 1951. That seemed to satisfy him.”

But Waverly veers toward American behavior as she pursues chess. Tan has her approach the game in a classically American fashion, the result of which is a classic American success story. First Waverly watches her brothers play, then begs them to teach her, and then takes more extreme measures to improve, studying fundamental strategies in library books, looking up words she doesn’t know, even drawing a chessboard and staring at it for hours. She accosts an old man playing in the park and convinces him to mentor her. She gives up social activities to study chess theory. In this way, she becomes a national champion and gets her picture on the cover of Life magazine. This is, in fact, the embodiment of the American Dream: no matter where you come from, if you have the smarts, take initiative, and work hard enough, you can achieve anything.

Tan makes this connection between chess and America even clearer when she has the mother conflate the rules of the two. As Waverly’s brothers try to teach her the game for the first time, the mother takes the rule book, gives it a cursory, uncomprehending glance, and concludes:

This American rules. Every time people come out from foreign country, must know rules. You not know, judge say, Too bad, go back. They not telling you why so you can use their way go forward. They say, Don’t know why, you find out yourself. But they knowing all the time. Better you take it, find out why yourself.

Once again, this shows the gulf between the Chinese culture the mother understands and the American culture that surrounds her. But this time Tan is careful to associate the principles of America and the conventions of the chess, and the mother seems to be asking Waverly to forge ahead in both. Waverly, of course, already understands what the mother doesn’t, and she is happy to advance within the American system of personal achievement.

Tan portrays the Chinese as caring less about personal achievement than they do about humility, harmony, and community. Waverly’s brother acquires his chess set at a church Christmas party, for example, and though it’s used and has two pieces missing, the mother exclaims to the unknown donor, “Too good. Cost too much.” As soon as they get home, she tells her son to throw the chess set away. “She not want it. We not want it.” The mother is clearly offended by the gift, but her public response shows her greater appreciation for humility and respect. Tan reinforces this as a cultural standard, not just a family quirk, when a boy from another family is visibly disappointed by his gift and gets smacked and then dragged away, his mother “apologizing to the crowd for her son who had such bad manners he couldn’t appreciate such a fine gift.” Later, when Waverly begins winning exhibition matches, her mother, nearly bursting from pride, is careful to maintain humility by announcing, “Is luck.” The community accord that results from such humility and deference allows the entire neighborhood to celebrate Waverly’s achievements collectively. The Chinese bakery displays her trophies, then frosts a cake declaring her “Chinatown Chess Champion,” and other businesses offer to sponsor her for national tournaments.

Tan lets us glimpse the monster shaping up beneath the ice by forcing these competing value systems into contact. There would be no cultural conflict about what do to with the turtles, for example, if white tourists didn’t venture into Chinatown. In the same way, Tan lets Waverly venture further into chess and demonstrates how it carries her away from the Chinese community and its values. When she improves enough to beat her brothers, for example, the tradeoff is clear: “Soon I no longer lost any games or Life Savers, but I lost my adversaries.” She advances according to American notions of success, but it costs her interaction with her family members. Her American pursuit, in other words, distances her from the Chinese world, sometimes quite literally: after winning two neighborhood tournaments, she “attended more tournaments, each one further from home.” And she “no longer played in the alley of Waverly Place. [She] never visited the playground where the pigeons and old men gathered.” Likewise, her behavior moves away from the humility and harmony the Chinese value. She stops doing dishes, refuses her finish her meals, and makes her brothers sleep in the living room rather than share her bedroom as they always had.

This culminates when Waverly accompanies her mother to the Saturday market and grows irritated by her mother’s vicarious pride, though it seems innocuous enough: “‘This my daughter Wave-ly Jong,’ she said to whoever looked her way.” Finally Waverly says she wants it to stop, and in the resulting argument, Tan finally pits the two sets of cultural values directly against each other, Waverly taking an American perspective of individual accomplishment and the mother taking the Chinese perspective of communal bonds:

“Aiii-ya. So shame be with mother?” She grasped my hand even tighter as she glared at me.

I looked down. “It’s not that, it’s just so obvious. It’s just so embarrassing.”

“Embarrass you be my daughter?” Her voice was cracking with anger.

“That’s not what I meant. That’s not what I said.”

“What you say?”

I knew it was a mistake to say anything more, but I heard my voice speaking. “Why do you have to use me to show off? If you want to show off, then why don’t you learn to play chess.”

It could be argued that Waverly is displaying a certain kind of humility here by asking her mother not to “show off,” but if so, it’s certainly not the kind of humility the Chinese in the story value. In every other example of it, the Chinese characters have displayed respect for the feelings of others above their own, whether in graciously accepting crummy gifts, downplaying personal success, or celebrating the success of others. That’s clearly not the case here. Waverly is putting herself first. She’s also denying her mother’s pride in their association, challenging the values of family and community. For Waverly, pride is reserved only for the individual who achieves something (“If you want to show off, then why don’t you learn to play chess”), not for the community that supports and enables it. All of this undermines the harmony that the Chinese values promote. And at this point, she rips her hand from her mother’s and runs away, severing their physical bond just as she has severed their cultural bond.

When she finally returns home, hours later, her mother instructs her brothers to ignore her as punishment: “We not concerning this girl. This girl not have concerning for us.” The story ends with Waverly sitting alone in her room, beginning to consider what her success at chess has cost her: “I was gathered up by the wind and pushed up toward the night sky until everything below me disappeared and I was alone.” This wind is an extended metaphor that deserves its own examination, though this is not the place for it. The basic idea is that Waverly rises so high that she ends up alone—or as we Americans like to put it, It’s lonely at the top.

And then comes the final line: “I closed my eyes and pondered my next move.” My students often complain that this ending seems abrupt, unfinished. In the anthology we use, it comes at the very bottom of the page, and students often admit to having flipped to the next page, expecting the story to continue. Usually I avoid telling them that it does continue in the collection of linked stories, because doing so allows students to dismiss the ending as a concession to the larger narrative or as something other than an ending. Instead, I direct them to the letter by Chekhov in which he famously instructs A.S. Suvorin, “You are right in demanding that an artist approach his work consciously, but you are confusing two concepts: the solution of a problem and the correct formulation of a problem. Only the second is required of the artist.” In other words, the writer’s job is, first, to write about questions complex enough that they avoid simplistic answers or easy moralizing and, second, to demonstrate such questions with precision and accuracy. The writer’s job is not, however, to answer them. Answers are not only reductive, they’re also political, prescriptive, moralistic, and this undermines the efforts of such realists to be “visible nowhere.”

And then comes the final line: “I closed my eyes and pondered my next move.” My students often complain that this ending seems abrupt, unfinished. In the anthology we use, it comes at the very bottom of the page, and students often admit to having flipped to the next page, expecting the story to continue. Usually I avoid telling them that it does continue in the collection of linked stories, because doing so allows students to dismiss the ending as a concession to the larger narrative or as something other than an ending. Instead, I direct them to the letter by Chekhov in which he famously instructs A.S. Suvorin, “You are right in demanding that an artist approach his work consciously, but you are confusing two concepts: the solution of a problem and the correct formulation of a problem. Only the second is required of the artist.” In other words, the writer’s job is, first, to write about questions complex enough that they avoid simplistic answers or easy moralizing and, second, to demonstrate such questions with precision and accuracy. The writer’s job is not, however, to answer them. Answers are not only reductive, they’re also political, prescriptive, moralistic, and this undermines the efforts of such realists to be “visible nowhere.”

This is exactly what Tan’s ending accomplishes. To show Waverly’s “next move” would provide an answer, and, as Chekhov says, that’s not her job. For as long as America has been a country—longer, even—immigrants and their children have found themselves standing on opposite sides of a cultural divide. The immigrants belong to the old world’s culture, the children to the new world’s. Tan emphasizes this problem by leaving us on the brink of Waverly’s decision: will she continue to pursue an American system of values despite its costs, or will she decide the cost is too high and return to her family and its Chinese values? This is the moment when the problem is, at last, fully articulated, which means Tan can end the story. It isn’t her job to tell us how to resolve such a complicated and pervasive dilemma, only to show what it’s like to be trapped within it. “Rules of the Game” accomplishes this with subtlety and precision, and that, among its many other pleasures, is what makes it a story I—and my students—love.