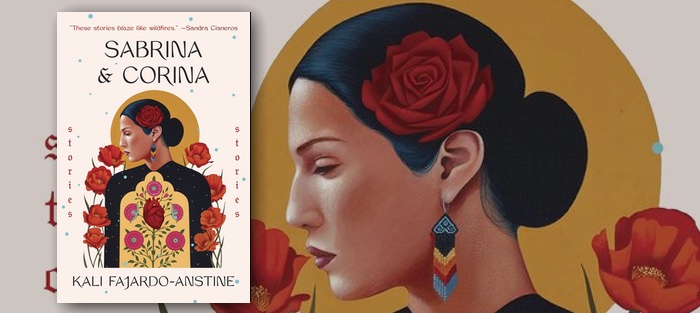

When a story collection is titled after an individual story within the book, that title story bears a heavier weight on its shoulders than the rest. This is perhaps no more clear than when the book title ends with “and other stories.” Yet there are collections for which one story or its title speaks so well to the themes of the book as a whole that the choice to title the book the same seems inevitable. Karen E. Bender’s story collections, Refund and The New Order, come to mind. Kali Fajardo-Anstine’s debut book, Sabrina and Corina (One World), is seemingly oddly named given that the stories collected are not all about the two title characters, and given that the title doesn’t, at first, seem to announce much in way of a theme. The story serves as a keystone in another way, though. Sabrina and Corina are cousins who, while once close as children, grow apart as their differing choices and opportunities lead them down divergent paths. From the onset of the story, we learn that Sabrina is dead, strangled. We soon learn that tragedy isn’t exactly foreign to the Cordova family. Years before Sabrina’s murder, when Corina’s father offers to pay her way through cosmetology school, to help set her on a path to be able to support herself, Corina tells us:

He said that I needed to do something besides run around like other Cordova women. He mostly meant Sabrina, of course, who by that point had started showing up to family dinners smelling like a barroom floor. But it wasn’t just her. There was the distant niece whose infant son was taken away by the state, the cousins who died messing around with heroin, Great-Auntie Doty left blind after a date with the wrong man, and Auntie Liz, found dead in her Chrysler, the motor running and the garage door locked. My grandmother hardly mentioned Auntie Liz except to say that what killed her had killed them all.

Many of the women Corina references here reappear in Kali Fajardo-Anstine’s book, beginning with Doty, who is the protagonist of the story that follows. Thus we learn that many of the characters throughout the collection are not only part of the same Coloradan Chicano Indigenous community, but they belong to the same extended family.

As the passage suggests, their stories are linked, too, by hardship. Women grapple with varieties of abandonment and betrayal—from absent fathers and abusive suitors to the gentrification of their neighborhoods and the theft of their ancestors’ remains. Their relationship to place is rich and complicated. Sierra’s mother in “Sugar Babies,” the opening story, seems to speak for the women of the collection as a whole when she says, “Ever feel like the land is swallowing you whole, Sierra? That all of this beauty is wrapped around you so tight it’s like being in a rattlesnake’s mouth?”

As the passage suggests, their stories are linked, too, by hardship. Women grapple with varieties of abandonment and betrayal—from absent fathers and abusive suitors to the gentrification of their neighborhoods and the theft of their ancestors’ remains. Their relationship to place is rich and complicated. Sierra’s mother in “Sugar Babies,” the opening story, seems to speak for the women of the collection as a whole when she says, “Ever feel like the land is swallowing you whole, Sierra? That all of this beauty is wrapped around you so tight it’s like being in a rattlesnake’s mouth?”

But, as the pair of names in the collection’s title reminds, Fajardo-Anstine’s book is also about the women who survive, the women like Corina, who live to tell their female relatives’ stories. For the funeral, Corina is tasked with the job of making her murdered cousin over. She brushes Sabrina’s hair, conceals the bruises on her neck. In making Sabrina beautiful again, Corina resists the story she knows her grandmother will tell of Sabrina—“how men loved her too much, how little she loved herself, how in the end it killed her.” Corina speaks up for her cousin, tells their grandmother, “Sabrina didn’t want any of this. She wanted to be valuable.”

“Remedies,” one of my favorite stories in the collection, contrasts Clarisa and her half-brother, Harrison. What they share is the same absent father, but whereas Harrison’s mother is rather absent, too, consumed by alcohol and pills, Clarisa’s mother goes to pained lengths to care for both her ex’s children, even though it means constant battles with lice every time she takes Harrison into her home.

The story also contrasts Clarisa’s mother, who tries countless store remedies for the lice, and Clarisa’s grandmother, Estrella, who finally gets rid of the lice problem for good with the application of a home remedy and her advice that her daughter stop making Harrison her responsibility. It’s the story of how Clarisa locates herself in the divide between the two matriarchs. Clarisa is the one who makes that call for her grandmother’s help, despite her mother’s warnings that Estrella cannot know about their lice problem. Toward the end of the story, Clarisa relays that before her grandmother died, she gave Clarisa a book with all her home remedies. Clarisa notes:

For the most part, I stick to over-the-counter remedies. They are cleaner and work faster and come in packages with childproof lids. But every once in a while, when I get a real bad headache and the aspirin isn’t cutting it, I take slices of potatoes and hold them to my temples, hoping the bad will seep out of me.

Sierra in the opening story, “Sugar Babies,” is divided, too, though not between two matriarchs; Sierra is divided by two feelings about her mother and about motherhood. Her mother abandoned her and her father a few years earlier, but as much anger and resentment as Sierra feels towards her mother, when her mother returns suddenly, Sierra soon feels herself pulled in by her mother. There’s a heartbreaking scene in which her mother offers to braid her hair, and Sierra pulls away only to then nuzzle close. She says, “I nearly fell asleep in her arms as I held Miranda in my own.” Miranda is the name she and her assigned partner at school have given the bag of sugar they must co-parent. Devastating, too, is the story’s end, what Sierra and the sugar baby’s father, Robbie, do after Miranda dies.

The contrast in “Sisters” is between the aforementioned Great-Auntie Doty and her sister, Tina, who is interested in finding them husbands:

[Doty’s] sister had a thing for Anglos. They made more money, they could live and go anywhere in the city, and Tina believed each of the sisters could end up married to one. After all, they were both light-complected. But Doty felt white men treated her as something less than a full woman, a type of exotic object to display in their homes like a dead animal.

Doty isn’t interested in men or marriage. She’s more interested in the fate of a missing girl, whose face appears on flyers papered across Denver. The man with whom Tina sets Doty up doesn’t kindly accept her disinterest in him, though.

At the end of “Sisters,” a girl asks Doty if people tell her she’s “lucky it wasn’t worse,” and Doty says, “As a matter of fact, no one says anything about it at all.” Of course, Kali Fajardo-Anstine is saying something about it. Her gritty and tender debut gives voice to so many women whose stories are rarely heard, and that’s another way the book’s title functions—to announce upfront whose stories these are.