Ellen Prentiss Campbell’s characters are wounded—often by their past, by choices made long ago. They think of paths not taken, choices in their youth that went wrong. Living, frequently, in unfulfilled marriages or relationships, they think of previous lovers and those moments of greater connection, envisioning the “what if” had they ended up with the person they loved long ago. Not all these wounds can be traced back to particular moments or decisions; others build up over time. For example, when a sibling feels their sister is the favored one—more talented, more vibrant and lucky. Or, when one child is adopted and the other not. Painful rivalries develop.

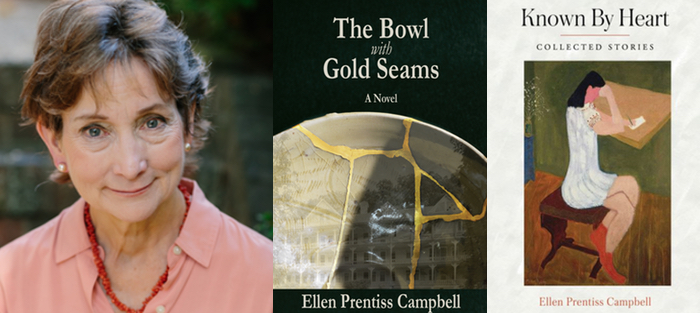

In the midst of all of these wounds, however, is also the desire of Campbell’s characters to protect others who are wounded, to somehow heal, or escape from their pain. In two linked stories in her new collection, Known By Heart (Apprentice House), a character falls in love with her husband when she is young, has an affair with another man before she marries, dreams about and maintains a correspondence with the man throughout their lives, and yet continues working on her marriage. Then she divorces her husband, only to remarry him a second time. The desire to return, to find some final way out of pain, sustains the collection. In two of the most moving stories, elderly characters lose their cognition with dementia and their sight; they lose their control as they age; but others nearby seek to protect them as they go through the process of aging and dying.

Three years ago, Campbell gave a powerful review of my collection of stories, Mexico. I didn’t know her at the time, but the review led to us subsequently meeting in Washington, DC and Mexico City. At those encounters, I could see her quiet meticulousness, which fits her precise and minimalist prose. Forced by the pandemic to keep our physical distance, we met via WhatsApp to talk about her new book.

Interview:

Josh Barkan: How has being a therapist affected the stories you write?

Ellen Prentiss Campbell: Greatly. The job for me was all about close listening. And close listening for what isn’t being said, but is important. So I’m listening, close listening, when I write, to the voice of the character, and what is perhaps unsaid.

Interesting what you say about “what isn’t being said.” That sense of underlying secrets comes through in your work and it’s part of the power. And I think that gets to some of the sense of what are the stakes in your writing. You mentioned, the other day, you thought my writing was different from yours in that the stakes were high. What are the stakes in your stories? What makes a good story?

This follows, too, perhaps from my work as a therapist, where I was in the position of being with people at times of personal conflict, choice, decision, pain. This made me keenly aware that there are high stakes, important issues, in everyone’s life—moments of personal choice. I think that the “stakes” in my stories come out of those struggles, internal or between people, which become moments of decision. For me, a good story is one where I as a reader can enter into and believe in the character’s struggle, which may be small in scale but large in personal impact—I love close third person.

This follows, too, perhaps from my work as a therapist, where I was in the position of being with people at times of personal conflict, choice, decision, pain. This made me keenly aware that there are high stakes, important issues, in everyone’s life—moments of personal choice. I think that the “stakes” in my stories come out of those struggles, internal or between people, which become moments of decision. For me, a good story is one where I as a reader can enter into and believe in the character’s struggle, which may be small in scale but large in personal impact—I love close third person.

You can feel that compression with your use of that point of view, that sense of agony over their struggles and personal choices. One of the hard things in fiction is to make a protagonist, who takes semi-ethical choices, empathetic. Your protagonists do things that are ethically mixed. Where does that impulse come from?

Impulse is the word; it is not a considered intention either in my writing or my own or my character’s actions. A mixture of light and dark, good and evil, self-interest and generosity absolutely seems to me part of the human condition, part of everyone. And it’s where the heat is.

That sense of impulsiveness, of the cost of impulsive battles between siblings and between romantic partners, comes throughout your collection. It’s a form of complication in your stories. And often, in your stories, there is a sudden complication, whether an affair revealed, or someone who has died driving their truck after it flipped, etc. What makes a good complication?

A good complication isn’t purely circumstance or coincidence—though I’m a big believer in circumstances and coincidences of fortune and timing as real and determinative parts of life as well as the kind of fiction I write, like to read. But the good complication requires a response, occasions a response, in the character, the reader, both sometimes, and re-frames characters’ understanding of self or others, or the reader’s.

The question of emotional stakes for characters is central to what I’m aiming for, and a good complication requires that to be an organic part of the problem.

Yes, you can feel your insistence on realism in your work—in the way complications come in. A sense that things can’t just be cooked up in order to push a story along. Yet there is plenty of drama. I wonder, sticking to that idea of realism, about your story endings. Some of your stories end quite quickly. Why? What makes a good ending? And does that have anything to do with your insistence on realism?

The image that immediately flashed into my mind with this question is that moment when a gymnast flings herself off the beam and “sticks the ending.” And that is not something I see as real, as a good ending. A story ends quickly—say in “Faith and Practice” at the bonfire—not like the final nailing of the gymnast trick, but because it’s often the moment before the character must go on to whatever comes next—the gymnast stumbles, regains balance, and is going to have to go on, but we aren’t going to witness it.

The good ending completes a story, but also just punctuates. I like an ending with a sense of more unrolling out of the story, off the screen.

So there is a sense of being suspended. Caught before everything resolves. A bit like Charles Baxter’s idea of “against epiphanies.” Though there are also epiphanies for your characters in your stories. I feel like rather than resolution coming at the end of your stories, in many ways it comes as the characters relive their experiences through memories. You do a nice job of jumping around in time, quickly cutting to memories, or from one scene of action to the next. What do you feel is the key to controlling time in a short story?

I love time and memory. I love the way our minds work with those elements, and fiction, too. And the way time clarifies and warps memories. I am a realistic writer, but the one sort of speculative fiction I love reading is time travel. I am not sure of what the key to controlling time in a short story is. For me as a writer working with time, one element is to be aware of sensory prompts that shift the character’s focus from present to past or even to assumed future. I think also there is a need for a shift, a character’s perspective undergoing a slight pulling back to a different distance or vantage point. The shutter on the mind’s eye clicks, there’s a readjustment of focus. And then a click, and a readjustment back.

A kind of zooming in and out, which captures the sense of reflection, of evolution of the characters. I think that’s what gives a strong sense of interiority to your stories, even though most are told in the third person. The characters are really evolving, introspecting, coming to terms with their feelings, their relationships to their siblings, the wrongs they may have done to others. I want to ask you about a different sense of zooming in and out, or structure. Some of the stories in your collection are linked directly. Others not. What are the challenges of putting together a collection like that?

Right. It is not a novel in stories, all stand alone, but there are at least two sets of recurring characters in a couple of stories, and those “linked” stories were written months apart, sometimes years apart. I heard poet Todd Davis talk about arranging and re-arranging his poems as he sought the right balance. That really spoke to me. I was at a point with my novel-in-progress where I needed a pause and literally began shuffling stories. It wasn’t exactly like playing solitaire, but there was a way in which certain stories had to be together that became clear. And it also revealed to me this underlying theme that shouldn’t have been any surprise to me—all these characters seeking connection, with another, present, remembered. Dealing with distance, emotional distance not the social distance we are caught up in now. Once I saw that, it was easy to shuffle the deck.

Right. It is not a novel in stories, all stand alone, but there are at least two sets of recurring characters in a couple of stories, and those “linked” stories were written months apart, sometimes years apart. I heard poet Todd Davis talk about arranging and re-arranging his poems as he sought the right balance. That really spoke to me. I was at a point with my novel-in-progress where I needed a pause and literally began shuffling stories. It wasn’t exactly like playing solitaire, but there was a way in which certain stories had to be together that became clear. And it also revealed to me this underlying theme that shouldn’t have been any surprise to me—all these characters seeking connection, with another, present, remembered. Dealing with distance, emotional distance not the social distance we are caught up in now. Once I saw that, it was easy to shuffle the deck.

There is a pleasure for the reader in seeing that shuffling, in finding characters recurring from one story to the next. And then, as you say, patterns begin to emerge, even when the characters are not carried from one story to the next. How themes carry from a story to the next also seems important to how we order story collections. Maybe this is a good time to delve into some of the specifics of the content of your latest collection, some of what emerges as a pattern, before I come back to a couple questions about your craft. Is your latest book, fundamentally, a book about loss?

I think of it as a book about love—but, of course, loss is inextricably part of love.

Yes, love. But also, as you say in terms of loss and love, the pain of love. What is the book saying about the nature of flaws in relationships/marriages and the desire for affairs?

Perhaps that circles back to the endeavor, the struggle to come to terms with imperfect lives. That desire and flaws are part of being human.

And it reminds me of what you’ve said, about writing about what you are burning to write about, something of substance, with something moral at stake. Well, again, I suppose coming to terms with imperfection is profoundly part of this. Empathy.

Yes, you feel that struggle with personal imperfection throughout the collection. Often regrets. That sense of personal moral responsibility and whether the characters can acknowledge their responsibility. It gives much of the emotional tension in your stories. I admire the way your older characters must struggle with the wrongs, in old age, they have done to other people they are close to over the course of their lives.

In terms of the struggles of the characters, another of the sub-themes is unwanted pregnancies, and abortions. What made you want to focus on that?

I think it’s related to the theme of longing and yearning we spoke about above, with some fear mixed in. I didn’t “want to focus” on any sub-theme. The sub-theme may be there, of course. With what I write it’s not a question of “wanting to focus” on a particular issue, the tea leaves just begin to settle, you know? For me, relationships between lovers, parents, children, siblings are compelling. The longing for and the fear of having children is also compelling. There are also characters in these stories who have feared to be parents, longed to be parents and are not, who have lost loved children…

Yes, I think that is the best way of putting it. We don’t start out writing about themes. We start with our characters, our stories. And then themes emerge. And that’s so important for writers to grasp so that their characters don’t become wooden puppets. That brings me back to the freedom of writing. That necessary freedom and why we write. As a last question: what do you feel is the fun part of writing short stories? What is most exhilarating to you as you do so?

The secret is that writing is such extreme fun. Is there a bumper sticker that says, “I’d rather be writing”? The most exhilarating part of writing short stories is maybe like using a potter’s wheel. I’ve tried once or twice, and you’re spinning this lump of clay without really having either full control or a full picture of the finished product. It’s messy and totally absorbing, and you eventually get there. Or not. You can always start over.