A short story is an urgent moment. A novel is a whole day.

A short story must measure each breath, justify every flashback, discard needless backstory, carefully pace, and propel readers to the end. If it takes on too much weight as it moves, it might sink. Readers are only offering a twenty or thirty minute sit of their time.

A novel is an investment. The reading stakes are high. Readers are willing to spend hours and days with hundreds of pages. We’re willing to spend emotion. It better have a payoff.

But it’s not just size. It’s scope. It’s depth and themes. It’s complexity of the plot.

A short story can rarely manage ten characters or multiple point of views. It takes a deep dive below the surface and we hold our breaths.

A novel has room for setting and can linger in language of aesthetics. The world you’ve created shifts. The characters you’ve imagined have time to change.

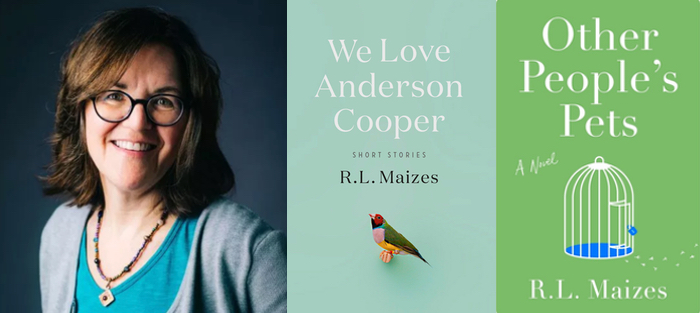

The tension between whether a story wants to be long or short requires us to examine them together. R.L. Maizes is both a successful short story writer and a debut novelist. In 2019, she published her first collection of stories, We Love Anderson Cooper, with Celadon Books. Her novel, Other People’s Pets, also with Celadon Books, is due out in July. I learned a lot of what I believe about the difference between the novel and the short story by comparison on these pages.

The tension between whether a story wants to be long or short requires us to examine them together. R.L. Maizes is both a successful short story writer and a debut novelist. In 2019, she published her first collection of stories, We Love Anderson Cooper, with Celadon Books. Her novel, Other People’s Pets, also with Celadon Books, is due out in July. I learned a lot of what I believe about the difference between the novel and the short story by comparison on these pages.

In full disclosure, I met R.L. Maizes at the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference five years ago. She brought many of the stories that eventually became her collection. I was attending as a novelist. It’s usually around 50,000 words that I admit I’ve failed another short story attempt.

“We Love Anderson Cooper” is the first story I ever read by Maizes. It’s the one that has to open this collection; it sets the tone for the rest and prepares you for quirky characters and identity struggles with compassion and humor. It’s a short story because it captures a moment: a young man steals the show at his own Bar Mitzvah by outing his sexuality rather than reading the homophobic Torah. It’s a combustible flash as the boy’s parents chastise him, “Why didn’t you talk to us first?…We would have understood. We love Anderson Cooper.” The punchline lands and the lights go out. The story is done.

In a similar singular act, “Couch” does everything a short story should. A therapist replaces the chairs in her practice with a magical couch that transforms her patients from depressed to joyful, from anxious to calm, from defeated to hopeful. Each character reveals and is healed just by sitting. The metaphor is contained enough for a short story and the cure only needs these satisfying pages.

When I read Other People’s Pets, the novel’s slow burn began and I had questions. I wanted to know the protagonist La La. Why did grief from her mother’s abandonment (twice) haunt her every day? How did her father believe teaching La La the tricks to home invasion, the family business, would fulfill his parental duties? When did La La first understand that she could communicate with animals? Beyond my initial intrigue, La La is on a journey and we agree to commit as readers to her companionship for 300 pages. She has to leave veterinary school—her ticket out of the life she was born to—to rescue her father. Her crossroads need the room of a novel and the many complications on her path can’t be contained to a short story. Her family tale and its many turns can’t be unpacked in a small box. La La has to wrestle through her past to find a way to her future. Maizes needs the extra-large size for all the La La has to learn.

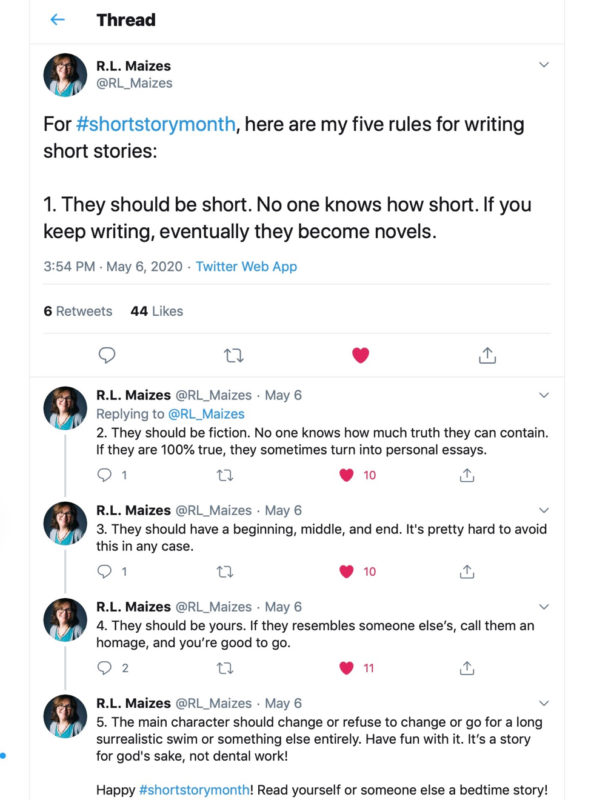

Luckily for us, Maizes cheekily tweets about the short story vs. novel debate and provides five rules for Short Story Month:

Rule #2 is my favorite. Maizes is intimating about the difference between something being true and containing truth. Fiction, whether it’s short or long, depends on trust between reader and writer. As readers, we are sharing our time and the deal is that it’s not to be wasted. Human truth, regardless of form, matters even if the events are imagined.

Maizes might agree with the master of truth in short story writing, Lorrie Moore. She adapted her introduction to 100 Years of the Best American Stories for Lit Hub on “Why We Read (And Write) Short Stories.” Moore calls a short story “a noise in the night.” She writes, “Short stories are about trouble in mind. A bit of the blues. Songs and cries that reveal the range and ways of human character. The secret ordinary and the ordinary secret.” A short story, Moore argues, often relies on truth and secrets but also on a world that has already been imagined for them that a reader will understand. It has to get to the point rather than do the heavy lift of world building a novel might indulge. And it must ring true even if it isn’t fact

T.C. Boyle might object to Maizes’ suggestion that short story writing might be fun. He explains the difference between prose length more painstakingly: “a short story is like a toothache and you must drill it and fill it. A novel is more like bridgework.” I’d argue that the writer who doesn’t run toward the dark or seek the pain isn’t a very good dentist, but the reward of a satisfying draft is worth struggle. The novel is a marathon and writing short stories might help you train for it, but the training is its own form. Training harder doesn’t mean you’ll run a successful marathon. You may just get an amazing workout and that is enough.

T.C. Boyle might object to Maizes’ suggestion that short story writing might be fun. He explains the difference between prose length more painstakingly: “a short story is like a toothache and you must drill it and fill it. A novel is more like bridgework.” I’d argue that the writer who doesn’t run toward the dark or seek the pain isn’t a very good dentist, but the reward of a satisfying draft is worth struggle. The novel is a marathon and writing short stories might help you train for it, but the training is its own form. Training harder doesn’t mean you’ll run a successful marathon. You may just get an amazing workout and that is enough.

Whether our work fits into the container of a short story or busts those seams wide open to be a novel is up to the writer and the tale they most want to tell. It’s our job to consider, to listen, and to decide what size fits best. It’s also about the risk we’re willing to take. It’s about the experiment we’re eager to embrace. A short story draft may take a day or a month but the revisions need twice the time. A novel draft might need a decade or years of plot mapping. Both short stories and a novel can be a burden, especially if they never reach readers. Both can be a gift, too, in story and in the writing lessons we learn. The only thing I know for sure right now is that I need them all, whatever shape, to help me live.