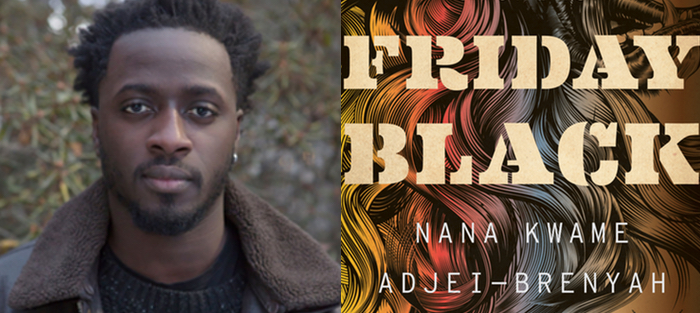

As we stand on what feels like the precipice of change, in the middle of an exhausting year, I find myself thinking constantly about Friday Black, by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah. It’s a strange, powerful, important collection, one that has only become more important and applicable since its publication in 2018 by Mariner Books. The book explores race, classism, and capitalism in ways that are often dystopian but resonate with the reality of American society today. It’s one of those books that exemplifies the power of fiction. Friday Black holds tenderness and violence in its hands, an unlikely pairing that makes it unforgettable and honest.

Of the twelve brilliant pieces in this collection, the opening story, “The Finkelstein 5,” is one of my favorites. It’s one of the most violent in the collection, but an undeniably honest representation of Blackness and the violence that faces Black bodies. The story follows a young Black man named Emmanuel, who narrates the story, beginning on the day of a job interview at a company specializing in producing vintage sweaters. His interview comes days after the jury delivered their verdict in a court case in which a white man, George Wilson Dunn, was acquitted of wrongdoing after being indicted for using a chainsaw to remove the heads of five Black children—later dubbed the “Finkelstein Five”—who’d been outside the library. A jury of Dunn’s peers decided that he’d felt legitimately threatened by the five Black young people, justifying the killing to protect himself. Days after the trial, a group dubbed “The Namers” begins killing white people, chanting the name of one of the murdered children. Before each attack, the members would decide which of the names of the victims to invoke. Emmanuel grapples with the aftermath of the verdict and attempts to figure out how to exist in an unjust society.

The first time I read this story, I was captivated by Emmanuel’s constant awareness of his Blackness. In this world, Blackness can be changed, so a person can project higher or lower amounts, based on their appearance, voice, and who they interact with. And after the verdict of the trial, Emmanuel begins to project his Blackness at a higher rate than he normally does. On the morning of his interview, he wears loose-fitting cargoes, patent leather Space Jams, a black hoodie, and a gray snapback cap, to stand in solidarity with the Finkelstein Five, which brings his Blackness up to a 7.6. Throughout this story, Emmanuel’s Blackness rises and falls, but as he searches for justice for the innocent school kids who were slaughtered, his Blackness rises.

The first time I read this story, I was captivated by Emmanuel’s constant awareness of his Blackness. In this world, Blackness can be changed, so a person can project higher or lower amounts, based on their appearance, voice, and who they interact with. And after the verdict of the trial, Emmanuel begins to project his Blackness at a higher rate than he normally does. On the morning of his interview, he wears loose-fitting cargoes, patent leather Space Jams, a black hoodie, and a gray snapback cap, to stand in solidarity with the Finkelstein Five, which brings his Blackness up to a 7.6. Throughout this story, Emmanuel’s Blackness rises and falls, but as he searches for justice for the innocent school kids who were slaughtered, his Blackness rises.

To tell of the Black experience, and to do it well, is a massive undertaking, and Adjei-Brenyah has done it phenomenally. He’s created emotional, honest Black characters who are figuring out how to exist in their worlds, which really aren’t much different from our own. Adjei-Brenyah writes, “Emmanuel started learning the basics of his Blackness before he knew how to do long division: smiling while angry, whispering when he wanted to yell.” There comes a day where Black children are made aware of their Blackness and how the world reacts to it. Parents have to have difficult conversations with their child about how to reduce their perceived threat. Keep your hands visible at all times. Keep your voice measured, calm. Say what you’re going to do before doing it. Adjei-Brenyah captures this in such a poignant, relatable way—one that isn’t dramatized or an exaggeration of what it’s like to be Black.

Existing in the world as a Black male, along with the mounting tension and anger from the verdict of an unjust court case, is something that Black people in today’s society knows too well. The brutal truth of this situation isn’t what makes the story dystopian—it’s what makes it true. As are the feelings of rage and the need for justice, for retribution, that the protagonist feels. Adjei-Brenyah writes, “He stared at the bat. The grinding, clicking heat in this chest hadn’t stopped churning since he’d gotten off the bus. It made him feel like the bat would cure everything if he could just grab it and bring it with him to the park.” The subtle shifts in the tension increases the feeling that Emmanuel doesn’t know what to do. It’s a feeling that resonated with me, as Emmaneul’s problems—despite their amplification in this distorted setting—felt so similar to my own.

As I re-read this story, it became clear that there was another question Adjei-Brenyah is wrestling with here: Is there a point where violence must be faced with violence? This is a question that our society continues to grapple with. When The Namers attack white people, they know that the survivors will never forget the name that they chanted. In “The Finkelstein 5,” and in today’s society, violence is crucially tied to both America’s brutal history and current events. Like Emmanuel in the this story, characters throughout the collection struggle with not knowing what to do, and not all of them figure it out.

Friday Black, while dystopian in its approach, tackles themes that are all too real in today’s society, including justice for Black people. Near the conclusion of the story, the lawyers’ closing statements are given. The prosecutor argues:

I happen to be one of the people who are perhaps foolish enough to believe there is a difference between good and evil. Somehow. Still. Please show me I’m not a fool. Show the parents of these children they aren’t fools for demanding justice. For knowing the idea of justice was born for them and this very moment. Mister George Dunn destroyed something. Maybe the only sacred thing. Show him it matters. Show him that you know these children, Tyler Mboya, Fela St. John, Akua Harris, Marcus Harris, and J.D. Heroy were humans with a heart, just like any one of you.

There are too many examples that could be pointed to in today’s society that mirror the case of George Wilson Dunn. It is hard not to hear the Florida prosecutor John Guy’s appeal to the jury during the George Zimmerman trial in this scene. At the core of this story, Adjei-Brenyah asks: When the justice system fails, how is justice to be achieved? It is perhaps this question that makes Emmanuel turn to violence; justice and violence are inseparable.

Seeing others exist in different spaces that I will never be able to occupy is part of what draws me to fiction, especially when it’s done as brilliantly as it is in Friday Black. Fiction allows readers to walk in shoes that they have never worn, and allows people to find themselves among its pages. I am not a Black male, but as a Black person, I saw myself in the collection. The topics and questions that Adjei-Brenyah tackle are questions that I grapple with in my life and in my writing. The stories here show simultaneously how life is lived and what it feels like to be Black, rendered in ways that are honest and brutal. Although Friday Black is a dystopian collection, it’s only futuristic on the surface. At the heart of each story is his truth, the truth.