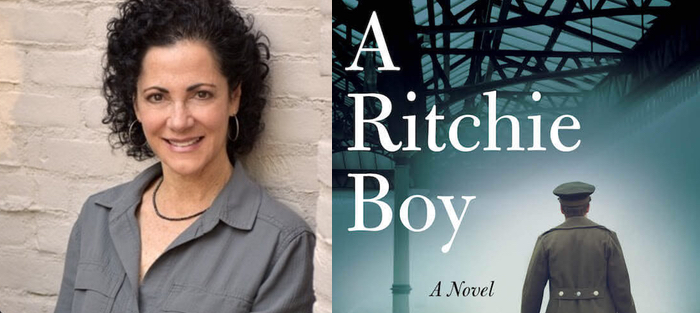

“I am a first-generation American, the child of Holocaust survivors,” Linda Kass tells me as we begin our conversation. “There is quite a bit of World War II in my DNA.”

Indeed, World War II provides a vivid background for the twelve linked stories that comprise her new book, A Ritchie Boy (She Writes Press), a beautifully-crafted family saga that introduces Eli Stoff, a refugee from Nazi-controlled Austria, who later enlists in the US Army, marries Polish refugee Tasa Rosinski, starts a family, and becomes an integral part of the Jewish community in Columbus, Ohio. Both Eli and Tasa are modeled after Kass’s parents, and the book pays loving tribute to their tenacity and fortitude as survivors. But unlike other stories of World War II that center on atrocities, antisemitism, and the difficulties of adjusting to American life—all of which are present in A Ritchie Boy—the book is a showcase for human resilience and bravery.

What’s more, Camp Ritchie, a 638-acre military outpost in the mountains of Maryland—used to train counter-intelligence personnel and interrogators before they shipped overseas—gives the book historical gravitas. It also provides a clear and vivid account of a once-secret US military division that played a decisive role in fighting the Nazis. As it describes the unit, the book pays homage to Ernest Stern, the author’s father, who was stationed at Camp Ritchie—one of more than 3000 soldiers later dubbed the Ritchie Boys.

Interview:

Eleanor J. Bader: Since A Ritchie Boy is loosely based on your parents’ experience as Jewish immigrants, I’m wondering if the war was a constant topic in your home when you were growing up.

Linda Kass: My mom was way more talkative about her past than my dad was, but I did not put their stories together until much later in my life. My academic training is in journalism, and when I was in my twenties, I was living in Detroit and working as a stringer for Time Magazine. The journalist in me saw my parents’ story of seeking safe harbor and surviving as incredibly important, and I knew I had to record and remember it. My children had to know from where they came.

As a kid, I knew that my dad had finished college on the GI bill, but he never, ever, talked about it until I sat down to interview him; I gave myself permission to ask at least some of the questions I had not asked before. I knew beforehand that he’d come from a working-class family, but the fact that someone he and his parents did not know—a total stranger living in the United States—signed an Affidavit of Support that got them out of Europe in 1938 was astonishing. I also learned about his time at Camp Ritchie during the war, but he did not provide a lot of details unless I asked for specifics. I knew, for example, that he’d started in the 10th Mountain Division in Colorado because he could ski, but after he caught rheumatic fever, he ended up getting diverted to Camp Ritchie. He was fluent in English and German so he was especially useful. Nevertheless, at that time I still didn’t know what a Ritchie Boy was. All I knew was that he’d been trained in interrogation and analysis. For some reason, I was cautious about asking too much about this period. After I did the interview, I typed it up–it was the 1980s so I used a typewriter—and put the pages in a drawer where they sat for decades.

How did the story find its way out of the drawer to become the foundation of A Ritchie Boy?

Back in 2007, my sister and I were trying to figure out what we could do for our parents’ upcoming 60th wedding anniversary. My sister reminded me that I had taken all these notes about their lives and urged me to put it together somehow. As I was thinking about how best to shape the information I’d collected, I was invited to a talk by Ohio State University (OSU) professor Lee Martin, the Pulitzer Prize-nominated author of The Bright Forever. After the lecture, I went up to him and told him a little bit about my family history. Lee invited me to audit a class he taught, a workshop in creative nonfiction. The class was wonderful and helped me shape the narrative into something I could give to members of my immediate and extended family.

Back in 2007, my sister and I were trying to figure out what we could do for our parents’ upcoming 60th wedding anniversary. My sister reminded me that I had taken all these notes about their lives and urged me to put it together somehow. As I was thinking about how best to shape the information I’d collected, I was invited to a talk by Ohio State University (OSU) professor Lee Martin, the Pulitzer Prize-nominated author of The Bright Forever. After the lecture, I went up to him and told him a little bit about my family history. Lee invited me to audit a class he taught, a workshop in creative nonfiction. The class was wonderful and helped me shape the narrative into something I could give to members of my immediate and extended family.

After this, Lee—who has since become a good friend—suggested I take his fiction writing workshop at OSU. I did and was immediately hooked. A short time later, I took a trip with my husband to visit our daughter. She was in college at the time and was spending a semester in Berlin. The three of us traveled to Vienna and to Poland, the countries of my heritage. This experience made me want to write fiction about my parents’ lives. The first book I wrote, Tasa’s Song (2016), was a novel about my mom.

But why did you opt to write the book as a novel-in-stories instead of a more straightforward journalistic account?

If I wrote this as nonfiction, the stories would be limited to the information I knew to be factual, interwoven with history of that time period. Even though I interviewed my parents, the information I gained are the basic facts of their lives—the persecution, the eventual escape, the particulars unique to each of them. I had a timeline of their lives, but I was not a witness to their day-to-day experiences and relationships. I couldn’t know their feelings or reactions to the events as they happened. I could say their history was marked by persecution, family love, resilience, and survival, but I was not there. I chose to make this a human story through fictional devices that allow you to inhabit characters in order to tell a human story. Fiction allows the telling of a larger truth. It allows the reader to experience, and be present in, that human narrative.

Did you ever feel constrained since the story, even as fiction, is loosely based on your parents’ lives?

No.

Let’s get back to A Ritchie Boy. What was it about you dad’s stories that provoked you to probe his military history?

One day, while I was visiting my parents and sitting in their living room, my dad showed me a letter he’d received about a Ritchie Boys reunion. Suddenly, I was able to connect the dots to his past as a soldier. I googled Ritchie Boys when I got home and immediately knew that I wanted to write about them, but, as I said, in a fictional format. At that time, I was deep in the throes of revising Tasa’s Song, but I started writing a short story that became “Zelda’s Gamble,” the third story in A Ritchie Boy.

In addition to speaking to your dad, did you do a lot of additional research?

I perused a lot of online sources and spent a lot of time reading issues of the Ohio State University newspaper, The Lantern, which were published in 1942, 1943, and 1944. I wanted to understand what was going on on campus. I didn’t interview other Ritchie Boys, but I did read quite a few accounts about them and watched a 2004 docudrama, called, simply, The Ritchie Boys. I listened to a lot of jazz from this period because Eli Stoff, my protagonist, and his friends frequented jazz clubs and loved music. I also read a lot of stories about the immigrant experience from the 1930s through the 1940s.

In addition, I researched what it meant to sign an Affidavit of Support for someone and read accounts of life in Columbus, Ohio, to learn about what the city was like in the 40s. Among other things, I discovered that neighborhoods were segregated and that there was still a lot of anti-Semitism after the War. Jewish people tended to live among one another, in communities where landlords would rent to them. This was presented realistically in the book.

The story in the collection called “When the Lights Dimmed” was based on the fact that Jewish families commonly opened their homes to newly-arrived immigrants and let them live with them until they got on their feet. And, of course, I wanted to get the details right. But because A Ritchie Boy is a work of fiction, I didn’t want the facts to overtake the stories. Yes, I found facts and created stories around them, but I had to imagine how this wealthy businessman, John Brandeis, got the Stoff family out of Austria, or how a young immigrant like Eli journeyed from one homeland to another, and got from boyhood to adulthood. And I wanted to imagine what the family’s life was like once they arrived and got settled.

Why did you write A Ritchie Boy as a novel in stories?

It was an unconscious decision. As I said, while I was revising Tasa’s Song, I started writing short stories. One, “Skiing in Tyrol,” was based on something my dad told me about how right before his family left Austria, he’d gone on a school ski trip. When he returned home, there were all these uniformed Nazis on the train platform. That image became the kernel of the first story in the book.

The stories did not come out of me in chronological order, but I present them that way because it makes the family’s life trajectory easier to follow. The format just made sense to me. I love the book Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout. It’s one of my favorites, and I realized I could write this book as a bunch of interconnected stories about one main character, Eli Stoff.

My favorite story in the book is “The Interrogation.” The compassion it exemplifies is something I wish more people were able to express, especially in our typical rush to judge and punish perceived wrongdoing. Was this based on something your dad experienced?

No. That was the third story I wrote. I have always been fascinated by Hitler Youth and I know that not every member—and maybe not even every Nazi Party member—was a true believer in Hitler’s ideology. I know that many young people were coerced into joining and had no choice but to sign up. I also know that my dad was stationed outside of Paris toward the end of the War and his job was to question Germans who were escaping into Paris from what we now know as the Battle of the Bulge. I imagined this soldier, Malcolm, who was not a Nazi supporter, who hated Hitler and the war, and was a troubled young man in a horrible situation. This piece was first published in the Winter 2019 issue of The MacGuffin literary journal.

A lot of what happens in the book struck me as lucky, serendipitous, or the result of chutzpah, sheer gall, in pushing forward. Was that what you intended?

I once heard someone define luck as the intersection of opportunity and preparedness. When I think back to my parents’ lives, sure, they were lucky, but they were also prepared. I wanted to convey that in the stories. My mother was separated from her mom for five years. She and her dad lived in an underground bunker for a year until the Russians liberated their village in 1944. After they were liberated, the two of them returned to their village in Poland because they knew that if their wife and mom—my grandmother—had survived, that’s where she’d go. The three eventually reunited and moved to America. Yet had my mother and her father not gone back to their previous hometown, this could not have happened. Is that luck?

I once heard someone define luck as the intersection of opportunity and preparedness. When I think back to my parents’ lives, sure, they were lucky, but they were also prepared. I wanted to convey that in the stories. My mother was separated from her mom for five years. She and her dad lived in an underground bunker for a year until the Russians liberated their village in 1944. After they were liberated, the two of them returned to their village in Poland because they knew that if their wife and mom—my grandmother—had survived, that’s where she’d go. The three eventually reunited and moved to America. Yet had my mother and her father not gone back to their previous hometown, this could not have happened. Is that luck?

My dad’s family was saved by a stranger, but people worked hard to make the connections that led to their ability to leave Europe. Luck does not fall from the sky. To some extent, we make our own luck.

Enough has been said about the cruelty of the Holocaust. Some got out, others did not. We know from many true and fictional stories that there was often some kind of intervention that led to a person’s escape—whether it was Oscar Schindler, or those Nazi-resistors who worked in secret to forge documents and escort victims in the dark of night to safety. In both of my parents’ circumstances, someone intervened to allow them to escape—that happened in reality and I tried to build that fact into the fictional telling of each of their stories. For my mother, a Catholic man who worked for her father at their small farm in eastern Poland built a bunker under the barn of his own home, where he hid her and several members of her family. For my father, an acquaintance of his mother’s, who had immigrated to the United States a decade earlier, took it upon herself to beg a wealthy Jewish retailer to take responsibility for him and his parents by signing an Affidavit of Support so they could get out of Vienna in 1938.

None of the characters in the book seem to feel guilty about surviving the war. Is this based on your family’s experience?

My dad was grateful that he got to the US and chose to pay it forward. He always gave back to the community rather than dwelling on what might have been. My mom spoke several languages and volunteered to help others by working as a translator for new immigrants coming in. They both lived in the present and together; they raised two kids and tried to assimilate, to become Americans.