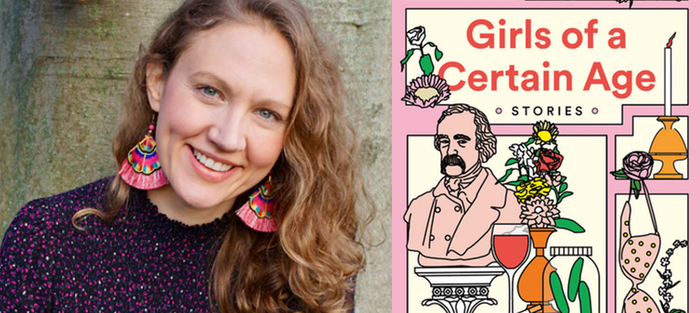

Maria Adelmann is an American fiction writer and author of the short story collection Girls of a Certain Age (Little, Brown and Company), which came out in February 2021. Kirkus praised the book, saying the stories were “illuminated by their artistry, honesty, and pervasive courage.” She has an MFA in fiction from the University of Virginia and her work has been published by Tin House, n+1, The Threepenny Review, Literary Hub, and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, among many others. A longtime resident of Baltimore, Maria ended up in Copenhagen after getting stuck there during the pandemic. Her debut novel, How to Be Eaten, will be published by Little, Brown in 2022.

I met Maria in Charlottesville in 2009, where we were part of the same MFA cohort at the University of Virginia. We spoke over Zoom in March 2021.

Interview:

Work–what people get paid to do, what happens when paid work disappears–comes up repeatedly as a topic that your protagonists worry about. As someone who grew up in a blue-collar area, I was always curious how people got paid to do things like paint paintings or write books. Can you tell me a bit about the types of work you did to support yourself before you got a book advance?

Right out of college, I got a job as a visual merchandiser at the corporate office of a company that went bankrupt during the financial crisis. I had thought, “Oh, I’ll go to work during the day and write at night.” But I couldn’t with an American job like that–I was up at 7 a.m., I went to work until 8 p.m., then I ate dinner, then I fell asleep. I didn’t write a single word–that’s why I applied to MFA programs. I thought if I wanted time to write, I’d better find a way to get paid to do it.

So that bought me three years. After, I did random jobs like copywriting and travel writing, but I made just barely enough to get by. My goal was to work freelance half time, write creatively half time, and that’s what I did until I got the advance. After that, I continued freelancing, but I had a little more flexibility with the financial padding. I don’t know how sustainable that model of working would have been for the long term or how sustainable it will be in the future.

I know you’ve done some teaching, but did you ever want to teach as a profession?

I’ve thought about it, but those jobs seem so difficult to obtain. Yes, if I could have a gig at a university or something, that would such a great way to maintain a stable income. I always think I can go into a teaching gig and focus on my own writing, but the fact is, I get really invested in my students: How are they doing? Am I giving them enough feedback? So it does take up all of your time, but then you get summers and breaks.

We met at an MFA program. What did you expect to get out of a writing program before you started, and what did you actually get out of it?

I was super turned off by MFA programs before I went–I assumed writing couldn’t be taught, and it seemed cooler to write outside of the system. As I said, I ended up applying for financial reasons, and then I ended up learning quite a bit about writing. I read more, I was around other writers, I could talk about books with other people. I met a lot of wonderful people, including you! Right before the MFA, I read a famous short story and I couldn’t understand it. After the MFA, I read it and the metaphors seemed so obvious–so clearly I learned something in between.

I was super turned off by MFA programs before I went–I assumed writing couldn’t be taught, and it seemed cooler to write outside of the system. As I said, I ended up applying for financial reasons, and then I ended up learning quite a bit about writing. I read more, I was around other writers, I could talk about books with other people. I met a lot of wonderful people, including you! Right before the MFA, I read a famous short story and I couldn’t understand it. After the MFA, I read it and the metaphors seemed so obvious–so clearly I learned something in between.

The bad part of the MFA is that you can get really critical of your own writing. The stories I wanted to write were not necessarily what most of my professors were interested in reading. Incidentally, I didn’t actually feel that I was very good. In my thesis defense, a professor asked, “When are your characters going to grow up?” But that was the point of the stories—those characters were growing up! I was writing to not-my-audience for my main instructional years. But I’d ask you the same question about the MFA program because I’m curious.

I was surprised by the number of people who were upper-middle class or at least supported comfortably by their families. For me, the benefits of post-grad programs in writing are having dedicated time to write and be critiqued, and to be around people with the same goals and interests. Is that worth paying for if your program doesn’t fund you? I don’t know that my answer is yes.

Also, my thinking is that an MFA program’s more recent function relates to the drawn-out collapse of the publishing industry. There used to be more people working in publishing, more magazines, and slush piles where unknowns could submit. There were more avenues to success, and now that there are so few, the MFA is taking up some of that filtering that used to happen at a professional level and has unfortunately become, for many people, a steppingstone to get noticed.

When I met you in our MFA, one of the first things I learned about you was your talent for craft and design. Each year, you design a corporate-style annual report about your life over the course of a calendar year that you send to family and friends. How does that sense of visual aesthetics intersect with fiction writing?

For me, writing is part of a larger creative drive, a craving to create something from nothing and to get obsessed with a project. Writers often get obsessed with a story or character. I can just as easily get obsessed with making pom-poms. I love the feeling of being in the creative world of the project versus the actual world. The stories in my book that I like best are like projects in that they rely on a conceit, like “Elegy,” which runs backwards through time.

Do you find something satisfying about making physical objects?

I like getting off the computer, whether it’s board games or crafts. When I watch TV, I have to also be doing a craft. I need to be busy all the time. It was hard when I was trying to write a book and my wrists had failed–I was physically struggling to write, and I couldn’t do crafts at all. I don’t handwrite much, but I do print my stories out, cut them into pieces, and move them around on the floor.

On that topic, what are your favorite board games?

You were playing “Pandemic” recently, weren’t you?

Yes. My husband’s a game designer, so he wins a lot, which is really annoying because I’m so competitive. There are some “literary” board games I really love, like “Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective,” where you investigate cases but also have a Victorian map and address directory along with the case notes. But tell me about your favorites.

I just got “Wingspan,” which I really like. I’m a bit obsessed with Uwe Rosenberg, who makes games like “Caverna” and “Agricola,” which are skill-based. I’ve heard them called “sandbox games”—because even if they’re multiplayer, you don’t interact with the other players that much. Really, you’re kind of playing the game with yourself, building your own little world. I have a similar experience with writing fiction—I want to make a world and live inside of it. The problem is that I tend to avoid conflict and tension in both my books and my board games.

OK, back to the book. One thing that links your characters is that they don’t feel comfortably established in the world. Sometimes it’s in terms of their financial situations, often it’s how they relate to other people. Why is that a point of view that felt interesting to you?

It’s truly my own point of view coming through.

My dad was a truck driver, my mom was a kindergarten teacher. There were lean years and better years. I had a good childhood and my parents made it work–I knew I couldn’t have everything, but we didn’t live in an extremely rich area, so I didn’t always notice. If they had said, “You can’t go skiing, because it’s too expensive” that seemed reasonable to me.

Cut to: Cornell, where I went to undergrad. I had a great experience there overall, but there were a lot of wealthy students, which was confusing. Many of them didn’t think they were wealthy, which was more confusing. There were people there who assumed certain things about themselves or their lives that I didn’t assume about mine. They just knew they would have the life they expected to have. Knowing you can fall back on your parents’ money allows you to take more chances, even if you never take your parents’ money.

Cut to: Cornell, where I went to undergrad. I had a great experience there overall, but there were a lot of wealthy students, which was confusing. Many of them didn’t think they were wealthy, which was more confusing. There were people there who assumed certain things about themselves or their lives that I didn’t assume about mine. They just knew they would have the life they expected to have. Knowing you can fall back on your parents’ money allows you to take more chances, even if you never take your parents’ money.

So, in a way, the essential difference is the anxiety of not having as much to fall back on, of choices feeling more limited.

And your awareness of that limitation. Let’s get back to your story collection. One of my favorites is “None of These Will Bring Disaster,” which is about a young woman who is recently unemployed and desperately seeking connection with other people. Though she’s a non-smoker, she signs up for a smoking cessation study in order to get free dental treatment. What can you tell me about the origins of this story?

I was laid off while working in visual merchandising, and I had a lot of dental problems at the time. Those were my only “office cubicle” years, which I ended up extremely disliking. Maybe I’m a writer because I was just like, no, I can’t do this.

Being on unemployment and having nothing to do felt super weird. I was a loner at the time; I wasn’t going out and drinking like the woman in my story. Then I read Deborah Eisenberg’s story “Days,” in which the main character quits smoking and tries to figure out what she actually likes to do, and I thought: wouldn’t it be funny if it were the reverse? If the character doesn’t know what she wants, so she starts smoking to fill that void?

Also, in college you could sign up for psych studies for money. I did a study about embarrassment. I wore a sandwich board out on the quad because that was the study–I was the loser trying to make five dollars. There’s a certain type of person who would subject themselves to a study like that.

Can you tell me a little bit about your relationship with the military and why the military comes up in your stories?

My brother was in the Air Force for a decade or more. The military is a way to pay for college. When he started college, there was no conflict, and then September 11th happened two months after he started. That was really jarring for me as a high school student. Now my family was part of a global conflict.

I wrote “How to Wait,” about a woman whose husband is going to war, thinking about my sister-in-law and what it would feel like to have your husband get deployed. I shared it with her before publication and she said, “Interesting, but not like my experience at all.” I stole the premise and imagined from there, which is what a lot of writing is for me.

You signed a two-book deal that was for your story collection and a novel, which wasn’t written, and for which you had to write a synopsis. What was it like to plan and sell an unwritten book?

It was terrible for me, personally. I had written fifty pages that didn’t even go together, mostly to show tone and style, and then a synopsis that was noncommittal to any sense of plot, which turned out to be a problem as I moved forward.

I thought of myself as short-story writer, so I wasn’t sure how to even write a novel. I felt constrained by the idea that I had promised something, which is always a problem for me. When I’m paid for work, I feel very stressed out. I wrote a whole draft and it was a million different stories. It wasn’t a novel. I had to write it all over again. It was quite a learning experience for me.

That makes me think that MFA programs in the United States are largely based around writing short stories, and short stories are all exercises in control. They’re so brief and you as a writer have complete mastery of the ecosystem and population. To go from that to being paid to write a novel that is based on a hastily written plot description is a totally different experience. It’s very odd.

It is. Right out of the gate, I thought I would write a “cheater novel,” something that thwarts the traditional narrative structure of a novel while still holding together as a substantial piece of fiction. A novel that’s really stories or something else altogether, like Lincoln in the Bardo, which I love.

It is. Right out of the gate, I thought I would write a “cheater novel,” something that thwarts the traditional narrative structure of a novel while still holding together as a substantial piece of fiction. A novel that’s really stories or something else altogether, like Lincoln in the Bardo, which I love.

Or like Elizabeth Strout.

Yes, like vignettes. Amy Tan’s book, The Joy Luck Club, which I love, is really a loosely connected short story collection. So I thought I would do it in that way, like a bunch of little projects, but it was so difficult. I made a lot of work for myself.

Can you tell me about your process for writing the book once the plan was established? What did that look like?

Well, you would know about this because you also sold a novel based on a synopsis. But it seems to me your natural location is the novel. When you were writing short stories it seemed like you actually wanted to be writing novels.

For me, the novel is a better fit. I don’t think I’ve ever really finished a short story. I mean, I was done with short stories. I closed documents that were short stories and did not open them again, and some of them may even have had the words “the end” written in them, but I don’t think any of them were great. It wasn’t until I tried writing a novel that I felt the pace and development suited my writing style.

It’s funny how people assume you can go back and forth, as if it’s natural. Like if you wrote poems, would someone say, “Now write a short story collection”? The short story to novel jump is as significant. They’re so different.

My novel is based on a premise that there are five women in group therapy who are modern versions of classic fairy tale characters. Little Red Riding Hood has been sleeping around, Gretel has an eating disorder–it sounds cheesy, but it’s dark and weird and about how the media has distorted their stories. One of the women is a contestant on a dating show much like The Bachelor. She’s our modern fairy tale character.

This allowed me to have, essentially, five novellas attached together with group therapy as the connective tissue. Not to do a board game callback, but they were like five little sandboxes for me to play in. In the synopsis, I didn’t say what their individual stories would be specifically. Mostly, I had to rely on the overarching premise, which I found difficult because I didn’t want to create the connecting sections at all, but I did have to fulfill that particular promise.

I actually wrote it in Scrivener. The document looks insane. Each story is intercut with therapy, and if you look at the left column where they’re all laid out, you might lose your mind.

Also, if there are five women in group therapy and each week they’re wearing different outfits, you have to track all of that stuff!

Continuity.

Yes. I wasn’t prepared to deal with it after the short story where there weren’t that many things to keep track of. I tried to write the novel in Word, but my brain couldn’t function that linearly. I wouldn’t have been able to do it.

Can you tell me what you’re reading?

Black Light, the short story collection by Kimberly King Parsons. It’s gritty, weird, and beautiful. I just read Luster by Raven Leilani. It was so funny, about a self-destructive woman, among other things, which is my jam. What else? For my annual report I write down every book I read, so let me open my notebook and look at the data. Cleanness by Garth Greenwell.

I heard that’s great, but I haven’t read it.

So good. It’s got the spirit of the short story in a novel. It has a “cheater novel” vibe. Also, Temporary by Hilary Leichter–it’s an absurdist novel about a woman who is a temp worker, but her jobs aren’t real jobs. She fills in for a barnacle, for example. It’s about the absurdity of capitalism and labor, how you become your job. I thought she couldn’t sustain it for a whole book, but then she did!